SEDE VACANTE 1503, I

August 18, 1503—September 22, 1503

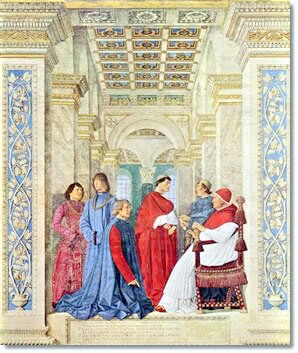

Platina is the kneeling figure,

Raffaele Riario is in blue, the future Julius II in the center.

and Pope Sixtus IV seated at the right.

No coins or medals were issued.

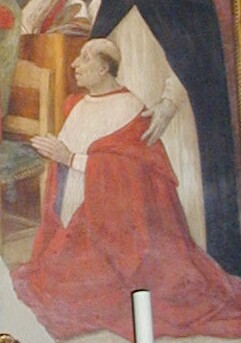

Raffaele Sansoni Galeotti Riario (May 3, 1461-July 9, 1521) was born at Savona, the son of Antonio Sansoni and of Pope Sixtus IV's sister Violentina. On December 10, 1477, while engaged in the study of law at the University of Pisa, he was created Cardinal Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro by his uncle Pope Sixtus (1471-1484). He was 17. He was suspected of having had some connection with the Pazzi conspiracy, April 1478, through his uncle Count Girolamo Riario and Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa. Although he was arrested and imprisoned, his uncle the Pope had him freed and brought to Rome, where he was officially rehabilitated in consistory. He was named Chancellor of the Church [Cardella III, 210; accoreding to Moroni 57, 171, he was named Vice-Chancellor], and in 1483 he became Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church, a post he held until his death in 1521. He was loaded with benefices by Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII (1484-1492), including the administration and income of sixteen rich bishoprics (including eventually Imola, Tréguier in France, Salamanca, Osima, Cuença [1479], Viterbo [1498], and Taranto); he was also Abbot of Monte Cassino and of Cava.

Under Alexander VI, however, he was in disfavor. The greed for power and property on the part of the Borgia family made the Riarios a major target. Alexander's son Cesare coveted the holdings of the Riario family, and seized the city of Forlì and also Imola. Riario fled to France and took up his bishopric of Tréguier. Giuliano della Rovere, too, was in exile in France, filling the post of Legate to Avignon. On his return in September of 1503 Raffaele was appointed Bishop of Albano (in November, 1503) and was consecrated bishop on April 9, 1504 by the new Pope Julius II personally (Giuliano della Rovere, another nephew of Sixtus IV). In 1507 he was promoted to the bishopric of Sabina, and on July 7, 1508, became Apostolic Administrator of Arezzo. Julius II made him Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, Porto, and Velletri on September 22, 1508. He participated in five conclaves, including the conclaves of 1484, 1492, 1503 that elected Pius III and the one that elected Julius II, and that of 1513.

In 1517, he was involved in the conspiracy of Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci against the life of Pope Leo X (also involving Cardinals Soderini and Sauli). He was arrested (May 29) and incarcerated in the Castel S. Angelo (De Grassis, p. 48). Trials were held. The ambassadors of England, France and Spain interceded. The College of Cardinals intervened on his behalf when it appeared that he might be stripped of all of his benefices, degraded from the cardinalate, and condemned to death. On July 24, he was released from confinement and brought to the Vatican; after he swore an oath, he was admitted to the presence of the Pope (De Grassis, p. 57). After he confessed to the Pope in a lengthy speech and begged pardon, which the Pope was pleased to grant, accompanied by a huge fine, whose value changed repeatedly, and the confiscation of his palace at S. Lorenzo in Damaso (the Cancelleria). He was restored to the bishopric of Ostia at Christmas, 1518, and his fine was cancelled. He died in 'retirement' in Naples.

Paris de Grassis, Papal Master of Ceremonies of Leo X, records his death in 1521 (p. 86):

Die nona julii mortuus est cardinalis Sancti Georgii, Raphael Riarius Savonensis, decanus colegii et episcopus ostiensis, qui cum esset aetatis suae anno decimonono creatus est a Sixto cardinalis, demum in vicesimo secundo camerarius in quo mansit annos viginti novem, et sic anno sexagesimoprimo vel circa obiit Neapoli. . . .

The Dean of the College of Cardinals in 1503 was Cardinal Oliviero Carafa (1430-1511), who had been made a cardinal by Pope Paul II in 1467. He was now 72. He became Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano in 1476, and in 1483 transferred to the Bishopric of Sabina. He participated in the conclaves of 1484 and 1492. After the Conclave of 1492, he was elected Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals in the place of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, who had been elected Pope Alexander VI. Since the see of Ostia was already being held by Giuliano della Rovere, he did not become Bishop of Ostia, the traditional prerogative of the Dean of the Sacred College. He had been named Administrator of the see of Naples just two weeks before Alexander's death.

The Governor of the City was Johannes de Sacchis, Bishop of Ragusa (1490-1505). On January 1, 1500, he had been named Regent of the Apostolic Chancery [Burchard Diarium III, 5].

The Secretary of the Sacred College, and Secretary of the Conclave, was Msgr. Adrianus de Caprinis of Viterbo, scriptor apostolicus [Burchard Diarium III, 269].

The Masters of Ceremonies were Johannes Burchard and Bernardus Gutterii.

Death of Pope Alexander VI

On August 1, 1503, Pope Alexander (Borgia) suffered the heavy blow of the death of his nephew, Cardinal Juan Borja, the Archbishop-elect of Monreale. His net worth was over 100,000 ducats, which went to the Pope and thus to Cesare Borgia [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 62; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 92-93]. The Venetians were greatly annoyed when the Archbishopric of Constantinople, which had belonged to the Venetian cardinal Michiel until his death and which the Venetians wished to be conferred on another Venetian subject, was instead given to Cardinal Juan Borgia, and now, on his sudden death, given (on August 9) to the Cardinal's nephew, Cardinal Francisco Lloris (Hiloris) [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 93].

On August 7, the Venetian Ambassador had an audience with Pope Alexander [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II,98-100], at which he found the pontiff non troppo allegro, piu renchiuso da l' aere del consueto. The Pope said to him:

Domine orator, questi tanti ammalati che sono a Roma adesso, e che ogni zorno moreno, ne fanno paura in modo, che semo disposti aver qualche piu custodia che non solevamo alla persona nostra.

August 11 was the anniversary of the election of Pope Alexander VI (Borgia) to the papacy. Antonio Giustinian, in his regular report to the Venetian Doge [Dispacci II, 102-106], notes that the Holy Father was more serious than usual, as were the Court, preoccupied as they were with the French army that was moving through Italy, heading for Naples. The Pope was being cornered into either supporting the French or genuinely remaining neutral (which did not go well with his continual favoring of the Spanish). On May 12, a battle between French and Spanish forces had taken place in the south. The Spanish captured Capua and and Aversa, and killed 1500 French troops. On the 13th the Spanish entered Naples [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 37; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 39-41]. Gaeta was under siege. A French relief force, led by Francesco Gonzaga, but directed by the Cardinal of Rouen, Georges d' Amboise, Louis XII's First Minister, was dispatched. On May 27, the Venetians had news that Cardinal d' Amboise was setting out from Blois [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 39]. On June 20, a new French Ambassador, Louis de Villeneuve, sieur de Trans, arrived in Rome quietly and privately, and next day had a meeting with Cardinal Sanseverino [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 43]. He was not received officially by the Pope until June 23, as the Pope kept trying to temporize, while seeming to favor both parties [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 78-79, 82]. In mid-August the French forces were already in central Tuscany, just north of Lake Bolsena, at Sutri, and they would have to cross the Tiber somewhere in the neighborhood of Rome. In the meantime, Duke Cesare planned a campaign in the Romagna, to the annoyance of Venice, Florence, Modena and Ferrara. The Spanish soldiers in the service of Cesare Borgia, Duke of the Romagnola, who garrisoned Rome and terrorized the neighborhood and the Campagna, were the natural enemy of the French. Cesare had been using his Spanish troops to seize Neapolitan territory in his own interest.

The Pope began to notice symptoms of illness on Saturday, August 12. The Badia of Florence, however, wrote to their ambassador to Louis XII on August 18 that the Pope had shown signs of a fever on the 10th and the Duke of Valentino on the 11th [Petruccelli I, 437]. He was supposed to have held a meeting for the signing of documents, but it was cancelled. It was announced that it was because of a slight indisposition of the Duke, Cesare Borgia, on the previous day, that is, on the 11th [Petruccelli I, 435, quoting a letter of Beltrando de Constabili, ambassador of the Duke of Ferrara, written on August 14, 1503]. In the evening Alexander showed symptoms of a continuous fever. He vomited yellow bile. On the morning of the 13th, the Pope had doctors summoned, one of whom (the Bishop of Venosa, Bernardino Bongiovanni) was ill himself; they were not allowed to leave the Apostolic Palace. The duke was also ill with a fever, accompanied by vomiting and stomach cramps; it was recognized as the all-too-familiar tertian fever. Cardinal Adriano Castello and nearly all of the officers of the Chamber were also ill. On Monday morning, the same symptoms that the Pope had shown on Saturday again afflicted him. He was bled on the 15th, thirteen ounces of blood being removed, and he showed signs of tertian fever [Burchard, 238]. Giustinian wrote to Venice [Dispacci II, 110], passing on the same information, but also that he had been approached by Cardinal Carafa (come quello che per autorità e per età li pare aver più parte in questo Pontificato) to intercede with Venice to do what it could to ensure a free papal election, should the worst come to pass. On the same day, the 15th, the Duke had his crisis, and there were signs that he was feeling better. On Thursday the 17th, around noon, Alexander was given medicine. Cardinal Francisco Borgia mentioned to the Ambassador of Modena, Beltrando Costabili [Petruccelli, 437; Pastor VI, 617-618] that the pope was feeling better and that he had a tertian fever, but there were fears that it would develop into a quartan fever. On the next morning, Beltrando was told by Cardinal Borgia that the pope had had a bad night and that the fever had gripped him even more strongly than before. The Venetian Ambassador, Antonio Giustinian, reported to the Doge of Venice on August 18, before the death of Pope Alexander, that the Pope was suffering from apoplexy, or so he heard from a reliable physician [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, no. 486, p. 118-120].

On Friday the 18th, Pope Alexander had confession, heard Mass, and received Holy Communion, seated on his bed, from the hand of Bishop Peter Gamboa of Carinola, the assistant Master of the Apostolic Palace and Vicar of Rome [Moroni, Dizionario 99, p. 92]. Five Cardinals were present: Arborensis [Jaime Serra], Cusentinus [Francisco de Borja], Monreale [Juan Castellar], Jaime Casanova and Constantinopolis [Francisco Lloris] (the 'Palatine cardinals'). Around sunset, at the hour of Vespers, he was given Extreme Unction by Bishop Peter Gamboa. Besides the Bishop only the Datary and the papal parafrenarii were present at Alexander's death, which occurred around 21:00 hours (hora vesperarum, according to Burchard). The Cardinal Penitentiary, Giuliano della Rovere, who should have performed these offices, was not in Rome; he was accompanying the French invasion force which was bearing down upon the city. The pope's son, Cesare, was not present either, being ill himself, but he sent one of his attendants, Michelotto [Coreglia, or Corella (as he spelled it: Gregorovius VII.2, 508 n.2)], to secure the pope's rooms and treasure. Micheletto demanded the keys from Cardinal Casanova, but when the latter refused, Micheletto drew a dagger and threatened to kill the cardinal and toss his body out the window. Casanova surrendered the keys. [Burchard, 238-239]. Caesare himself, whose political and military situation had changed radically in a single moment, was, according to Giustinian, opening negotiations for the services of Prospero Colonna. Burchard takes care to note that Cesare never visited the Pope during his illness, or when he was dead.

Burchard himself was present along with his associate, Bernardus Gutterii, to supervise the post-mortem arrangements. The body was washed by one Balthasar, familiaris sacristae, and certain other servants of the Pope, and dressed. The body was placed in the room next to the death chamber, on a litter, covered with decorative cloths. Near sunset, Bernardus called Burchard, who notes that none of the Cardinals had yet been summoned. Indeed, none came that evening, because (according to Cardinal Carafa) of the imminent danger. It was Carafa who notified the rest of the Cardinals after sunset, and advised them to come next morning to the Sacristy of the Minerva for a meeting. When Burchard returned to the Papal Palace, he personally dressed the body in full pontifical vestments, and then had the body transferred to the Camera of the Pappagalli. Two candles were placed next to the body. No one was present through the night. The Protonotaries, however, had been summoned to recite the Office of the Dead [Burchard Diarium III, 239-240].

On the 19th, the body of the pope was put on view in the Camera of the Pappagalli, vested in full pontificals. Four Franciscan penitentiaries said the Office for the Dead before the body, which was then transferred to the Vatican Basilica, with the Canons of St. Peter's, members of the papal family, and the members of various religious orders of the city taking part in the procession [Gregorovius' account (Volume 8, p. 2), is nonsensical]. The body was followed by Didaco, the Bishop of Zamora, the Papal Majordomo and by Peter the Bishop of Carinola, his deputy, [Burchard, 240-241]. The Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica, Cardinal Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara, was not present to receive the body. He was ill in Florence, having broken his leg in his haste to reach Rome, and did not attend the Conclave at all [Sanuto 102].

Rumors and Theories of Poison

The body was viewed on the same day by the Ambassador of Modena, Beltrando Costabili, who wrote that many people had no doubt that Alexander had been poisioned [Burchard 243 n. 1]:

El corpo del Papa ha stato tuto ogi in Sancto Petro, scoperto, cossa brutissima da vedere, negro et gonfiato, et per molti se dubita non li sià intravenuto veneno.

A similar report was sent by Giovanni Lucidio Cataneo to the Marquess of Mantua [Pastor VI, 618-619].

Gossip about poisoning was widely spread, and appears in Onuphrio Panvinio [in his continuation of Platina's Historia...de vitis Pontificum Romanorum, 562; Panvinio was familiar with Raffaele Maffei of Volaterra], though it is presented as an accident, the would-be murderers becoming the victims. It also points out that Cesar Borgia practiced homeopathic medicine, taking small amounts of poison in order to immunize himself against poison:

in cena, dum ad Umbrosum Vaticani vinis fontem, venenum bibunt, medicata Falerni vini Lagena, pocillatoris errore commutata, quam dira fraude ad opulentiorum aliquot senatorum, qui convivio aderant, exitium, honoris specie paravisset. Caesar qui dilutius biberat, esquisitis antidotis, vel ipso vivente robore, veneni vim substinente; atrocisimo quidem, sed non letali morbo correptus est, sicut magnis stipatus copiis dux acer, sibi usui esse nequierit, et dilabentes copias, duosque veteres hostes paucissimis diebus pontifices creatos viderit. At pauper Pontifex iam senio gravis quum non diu veneni vim ferre posset, Romae in Vaticano ad xv. calendas Septembris, anno salutis M[C]DIII aetatis circiter altero, et septuagesimo pontificatus vero xi. die viii est extinctus.

Panvinio seems to have picked up a story similar to the one that was reported to Venice, and which appears in the Diaries of Marino Sanuto at the very end of the month of September, 1503 [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 104-105]. Panvinio's source may have been Paolo Giovio, Historiae sui temporis (Book VIII; Tomus primus, p. 346 ed. Basel 1567):

eodemque die [February 22, 1503] ab Alexandro pontifice ad constitutum tempus Baptista Ursinus in mole Hadriani cantaridum veneno sublatus est. Sed Italicae nobilitatis stirpes excindenti, affectantique regnum Italiae, non diu Fortuna arrisit: quum coenaret enim Vaticana in villa invitatus a patre pontifice venenum bibit, quod convivis quibusdam senatoribus ditissimis paratum erat, fallente lagenae incaute a poculis ministro. Sed Alexandro vim veneni non ferente, ipse Caesar paterno funeri miseriaeque suae interfuit.

In his Life of Pope Leo X, Paolo Giovio has a more grandiose conception, that Pope Alexander was systematically murdering the richest of the Cardinals by poisoning them [Le vite di dicenovi huomini illustri (Venezia: appresso Giovan Maria Bonelli 1561, p. 105]:

... Perciò che 'l Papa per paura del disagio rapace, et per quel suo scelerato ingegno crudele, per non lasciar mancar danari à Cesare suo figliuolo, il quale manteneva esserciti grandi, et con pompa reale per tutto liberalità dimostrava, aveva fatto morire di veleno tutti i piu ricchi Cardinali; con animo senza dubbio alcuno per speranza dell' eredità, d' incrudelire ne gli altri Prelati di corte nobili di beneficij, et di ricchezze, se non che per mirabile providenza di Dio, questo huomo scelerato in causa della religione, et quello ch' era d' importanza allo stato d' ogn' uno, nato per ruinare Italia, a se medesimo la morte, et à Cesare suo figliuolo partorì l' ultima ruina. Conciosia cosa che in una allegra cena, scambiato per errore del otttigliere un fiasco à una ombrosa fontana della vigna di Belvedere beverno il veleno, il qual con inganno crudele sotto specie d' onore avevano apparecchiato ad alcuni Cardinali ricchi. Morto Alessandro, et appena avendo potuto Cesare con rimedij esquisiti, et nel fior della giovanezza sua riparare alla furia del veleno, si ferrò il conclave, dove Francesco Piccolomini, il quale gagliardamente era stato favorito da Giovanni, fu creato Papa col nome di Pio Terzo....

It was already reported in Venice in a letter of September 9, 1503, that Duke Cesare had gone off to Nepi, suffering from a fever; si tien certo sia sta avenenato insieme col papa a un cena i feno dal Cardinal Adriano [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 83; Tomaso Tomasi, Cesare Borgia, pp. 282-285]. In the version sent to Venice at the end of September, the setting was more specific: a garden party in the vinyard of Cardinal Andreano Castello of Corneto, not in the Vatican gardens, and it was a poisoned dessert, not a glass of wine; Pope Alexander had planned to poison the Cardinal to get his money and benefices; this the Cardinal suspected, though it is not said how or why he came to the suspicion. By switching plates of sweets with the connivance of the Pope's steward, the Cardinal poisoned the Pope instead. In this version, there are two would-be murderers, Pope and Cardinal.

Yet another version appears in the Life of Alexander VI in Mansi's Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, Volume 32, p. 523, and in this version as well, the poisoning is an accident; the medium is medicated wine, not the after-dinner dolce; and the culpable party is the cupbearer (is qui pocula ministrabat), not Cardinal Castello or the papal seneschal:

De quo hoc est memoratu dignissimum, quod cum in exitium opulentionum cardinalium prandium instituisset, is qui pocula ministrabat, merum veneno medicatum per errorem patri filioque propinaverit, atque ita patri pontifici qui septuagesimum agebat annum, et venenum plenius hauserat, violentam mortem intulerit, anno domini millesimo quingentesimo tertio XV Kalendas Septembris, cum sedisset annos undecim et dies octo.

But such stories, equally unlikely, accompanied the death of many popes, even into the twentieth century (e.g. Clement XIV, John Paul I). Like all conspiracy theories, they eschew the actual evidence and the likeliest explanation. Those who find it difficult to believe in the very rapid decomposition of the pope's body, absent some poison or other, should read the narratives of the transportation of the body of Pius XII from Castelgandolfo and its lying in state in St. Peter's Basilica in 1958 [F. A. Burkle-Young, Passing the Keys (New York 1999) 87-94; see the sensible remarks of Mandell Creighton, pp. 44-45]. The plain fact is that the doctors were treating both Alexander and Caesare for malaria. Alexander was certainly being dosed with medicines. Others in the papal retinue suffered from the same disease, and several of them died during the same summer. The Orator Francesco Fortucci wrote to the Ten at Florence on July 7, Ci sono di molti malati di febre, e ce ne muore assai bene. On the 20th he wrote, mi sono sentito et sento di mala voglia, et sono mezo fuori di me, oltre allo spaveto che ho, perche qui ne muore assai di febre, et ancho intendo che c' e qualche cosa di peste. On the 22nd he was well enough to visit Rainaldo Orsini, the Archbishop of Florence (1474-1508), who was in Rome, but who was indisposed with certe febre [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 99 n. 1]. The French ambassador Msgr. Tran was ill at Pontecorvo with a fever [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 93 (August 1, 1503)]. There was plague in the Spanish camp two miles from Gaeta.

The Cardinals:

There were forty-six living cardinals. Thirty-seven participated in the Conclave. Sanuto, V, 86, 100-103. Burchard, p. 267-271. Panvinio, 361-362. Cardinal Giovanni Battista Orsini of SS. Giovanni e Paolo died on February 22, 1503 (of poison, Paolo Giovio says at the beginning of Book II of the Life of Leo X; and see Tomaso Tomasi, Cesare Borgia, p. 277); Frederick of Poland of S. Lucia in Septa Solium died on March 21, 1503; Cardinal Giovanni Michiel, Bishop of Porto, had died on April 10, 1503; Cardinal Petrus d'Aubusson of S. Adriano died at Rhodes on July 3, 1503; Juan Borgia of S. Susanna died on August 1, 1503.

Twenty-five votes were needed to elect.

- Oliviero Carafa (aged 74), Neapolitanus, son of Francesco Carafa, grandson of Carlo "Malizio" Carafa, nephew of Diomedes, first Count of Maddaloni (d. 1487); his mother was Maria Origlia, daughter of Giovan Luigi, Signore di Vico Pontano, and Anna Sanseverino. Cardinal Bishop of Sabina (1483-1503). Legum Doctor (Naples). Apostolic Administrator of Salamanca (1491-1494). Legatus a latere to France in 1470. He had commanded the papal navy against the Ottoman Turks from 1471 to 1474. Chamberlain of the Kingdom of Naples (1477-1478). Protector of the Ordo Praedicatorum, from 1478. Abbot commendatory of S. Maria de Cava, from 1485. He was a staunch supporter of Ferrante of Naples. His brother, Alessandro Carafa, the Archbishop of Naples, died in Rome on July 31, 1503 [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 95; Zigarelli, Biografie dei vescovi ed arcivescove della Chiesa di Napoli, 111]. It was Oliviero Carafa who erected the famous statue of Pasquino outside his house near the Piazza Navona Died January 20, 1511. See: Alfred de Reumont, The Carafas of Maddaloni: Naples under Spanish Dominion (London 1854) 138-141. He is called "Prior collegii cardinalium" [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 100].

- Giuliano della Rovere (aged 64), son of Raffaele della Rovere and Teodora Manerola. His brother Giovanni had been Prefect of Rome from 1475; he died in November, 1501 [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 174], and was succeeded by his son Francesco Maria [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian I, p. 39; 87 (August 10, 1502)]. Nephew of Pope Sixtus IV. Bishop of Ostia, Major Penitentiary, once Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in vinculis (1471-1479). S. Pietro in vinculis Protector of France in the Roman Curia [See e.g. a letter of instructions to him from Louis XII, February 4, 1499, in G. Molini, Documenti di storia Italiana I (Firenze 1836), pp. 30-32]. Bishop of Avignon (1474-1503). He was also Legate in Avignon [Gallia christiana 1, 842; Molini, Documenti di storia italiana II, p. 26 (January 15, 1495); Diarii di Marino Sanuto 1, 138 (April 27, 1496)]. On June 5, 1496, he and Cardinal Briçonnet and the Florentine ambassadors were trying to induce Louis XII to invade Italy [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 1, 198]. On June 18, 1501, the Pope was compelled to invest King Louis with the Crown of Naples [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 61].

Pope Alexander had attempted, in June of 1502, to have him seized and immediately brought to Rome, sending Cardinal d' Albret and the papal secretary, Francesco Trochia [Eubel II, p. 56 no. 651; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian I, 31 (June 22, 1502); 46-47 (July 1, 1502)] to carry out the deed. On July 28, 1502, Louis XII entered Milan, in the company of King Federigo of Naples, the Duke of Ferrara, the Duke of Urbino, the Marchese di Modena, the Marchese of Monserrat, the Marchese of Saluzzo, Cardinal Georges d' Amboise, Cardinal Trivulzio, Cardinal Riario, Cardinal Sforza, Cardinal Ferreo, Cardinal Orsini, and Cardinal della Rovere [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 296, 306]. In December, 1502, the Pope revoked the privileges of Cardinal della Rovere [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 495]. Della Rovere was at Savona when the Pope died [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 70]; he made his entrance into Rome on September 4 [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 82]. Cardinal Giuliano was the future Pope Julius II. - Jorge da Costa (aged 97), Ulixiponensis, Bishop of Porto and Santa Rufina (April 1503-1508), once Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1489-1508). Former Confessor of the King of Portugal. He died on September 18 or 19, 1508, agens secundum supra centesimum (annum). His memorial inscription in S. Maria del Popolo: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 333 no. 1267.

- Geronimo (Girolamo) Basso della Rovere, Rencanatensis, Bishop of Tusculum (1492-1503), once Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1479-1492), and before that S. Balbina (1477-1479). Bishop of Recanati (1476-1507). Bishop of Albenga (1472-1476). He died on September 1, 1507. Son of a sister of Sixtus IV.

- Lorenzo Cibo [Genuensis], Bishop of Palestrina, fromerly Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1491-1503), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1489-1491) Archbishop of Benevento (1485-1503), Beneventanus, nephew of Pope Innocent VIII.

- Antoniutto Pallavicini (aged 62) [Genuensis], son of Balbiano Pallavicini and Catherine Salvago. Bishop of Albano, formerly Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1489-1507), once Cardinal Priest of Santa Prassede (1488) [Eubel II, 21]. Bishop of Ventimiglia (1484-1486) Bishop of Orense (1486-1507) Papal Datary of Innocent VIII, 1484-1489. He died on September 10, 1507, at the age of 66 [Gulik-Eubel Hierarchia catholica III (1923), p. 124 n. 2]. His memorial inscription is in S. Maria del Popolo: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 333, no. 1264, his body having been transferred there from S. Peter's in 1596 when the old basilica was being demolished. "Santa Prassede" He went into the Conclave believing that he would be made pope, with the support of the Spanish faction [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 200].

- Giovanni Antonio de S. Giorgio (Sangiorgio) [born in Milan], Alexandrinus, Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereus and Achilles (1493-1509). Professor of Canon Law at Perugia. Provost of the Basilica of S. Ambrogio in Milan. Archpriest of the Basilica of S. Ambrogio. Auditor of the Sacred Palace. Named Bishop of Alessandria by Pope Sixtus IV in 1479 (1479-1499). Transferred to the Diocese of Parma (1499-1509).

- Bernardino Carvajal, Carthaginiensis, Cardinal Priest of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (1495-1507). Legate in Lombardy (1497) [Burchard Diarium II, 359]. He was in the camp at Gaeta in early August of 1503 [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 95-97 (August 4, 1503)].

- Domenico Grimani [Venetus], Aquilegiensis, Cardinal Priest of San Marco (1503-1510), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Nicolai ad imagines (1493-1503).

- Georges d' Amboise, son of Pierre d'Amboise, Sieur de Chamont, and Anne de Bueil de Sancerre, sister of the Marshal of France. Rothomagensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (1498-1510). Archbishop of Rouen (1493-1510). Archbishop of Narbonne (1491-1493). Bishop of Montauban (1484-1491). Protonotary Apostolic. On September 7, Rouen, Sforza and Aragona arrived in Florence [Luca Landucci, Diario fiorentino ed. del Badia (Firenze 1883), 260]; they arrived in Rome in the evening of September 10 [Burchard Diarium III, 262]

- Jaime Serra, Arborecensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (1502-1510), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Vitale (1500-1502). He had been Vicar of Rome for Alexander VI, from ca. 1496 until his appointment to the cardinalate in 1500 [Moroni Dizionario 99, p. 92]. Legate in Perugia, returned to Rome on April 21, 1501; leaving Rome again on December 3, 1502. He paid 5,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Francisco Borgia [born at Sueca, near Valencia], Cosentinus, Cardinal Priest of Sta. Caecilia (1500-1506). Archbishop of Cosenza (November 6, 1499-November 4, 1511). Bishop of Teano (August 19, 1495-1508). Papal Treasurer [Burchard Diarium II, 340 Thuasne (November 27, 1496); 356 (February 12, 1497); 458 (April 21, 1498); 573 (November 3, 1499)]. Cubicularius of Pope Alexander VI [Burchard Diarium II, 57 (March 25, 1493)]. Son of Pope Callistus III (Alfonso Borgia). He paid 12,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Juan Vera, Salernitanus, Cardinal Priest of Sta. Balbina (1500-1507). Legate in the Marches of Ancona until October, 1502; replaced by Cardinal Farnese. He paid 4,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Ludovico Podocatar [born at Nicosia on the Island of Cyprus], Caputaquensis, Cardinal Priest of Sta. Agatha (1500-1504). He paid 5,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77]. Bishop of Capaccio (1483-1503). Papal secretary [Burchard Diarium II, p. 105 (April 1, 1494); III, p. 5 (January 2, 1500); Molini, Documenti di storia italiana II, p. 29 (September 29, 1498)]. Prelatus Palatii [Burchard Diarium II, p. 15 (December 11, 1492)]. Secretary of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (before he became Alexander VI). Died August 25, 1504. His memorial inscription in S. Maria del Popolo: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 332, no. 1260. "Capaze"

- Antonio Truvulzio, Comensis, Cardinal Priest of Sta. Anastasia (1500-1505). He paid 20,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Juan de Castro (aged 72) [Valencia, Hispania Citerioris], Agrigentinus, Cardinal Priest of Sta. Prisca (1496-1506). Bishop of Agrigento in Sicily (1479-1506). He was Castellan of the Castel S. Angelo at the time of his creation as Cardinal [Burchard Diarium II, 264 (February 19, 1496)]. His memorial inscription in S. Maria del Popolo: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 332 no. 1259.

- Giovanni Stefano Ferrero, Cardinal Priest of S. Vitale (1502-1510) Bishop of Bologna (1502-1510). Bishop of Vercelli (1493-1502). Student of Canon Law (Pavia) "Bononiensis"

- Juan Castellar (aged 61) [born in the Diocese of Valencia, a relative of Pope Alexander VI], Tranensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (d. 1505) Canon of Seville, Canon of Naples, Canon of Burgos, Governor of Perugia (1493). Protonotary Apostolic. Archbishop of Trani (1493), and of Monreale in Sicily (August 1, 1503–January 1, 1505).

- Francisco Remolino (aged 41) [born in Lerida in Catalonia], Perusinus, Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (d. 1518) Originally married. He studied law at Pisa. He was secretary to the King of Aragon, who appointed him Ambassador to the Holy See. Made Protonotary Apostolic through the patronage of Cesare Borgia. Governor of Rome (ca. 1497-1503) [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 29; Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 5, p. 380 (September 22, 1500)]. Locumtenens for Cardinal Raffaele Riario as Camerarius S.R.E. Archbishop of Sorrento, by appointment of Alexander VI (March 31, 1501-1512). He died on February 15, 1518. "Surentinus"

- Francesco Soderini (aged 49) [born in Florence], Volaterranus, Cardinal Priest of Sta Susanna (1503-1508). Professor of Law at the University of Pisa at the age of 23. (d. May 17, 1524). His brother Piero had been Gonfalonier of Florence. On July 15, he was in Florence, having returned from his embassy in France along with the French army [Luca Landucci, Diario fiorentino (ed. del Badia) (Firenze 1883), 257]. He arrived in Rome in the evening of August 30, 1503 [Burchard, 254].

- Niccolo Fieschi (aged ca. 47) [of Genoa, of the family of the Counts of Lavagna], Foroliviensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca. Doctor in utroque iure. Former Genoese ambassador to the King of France. Provost of Toulon. Bishop of Agde. Bishop of Fréjus (1485-1487). Under Julius II he was Legate a latere to the King of France, François I. (d. 1524)

- Francisco de Sprats [Des Prats] (aged 49), Legionensis, Cardinal Priest of S Quirino e Baccho (?). Bishop of Leon, Spain (December 4, 1500–September 9, 1504). Bishop of Astorga (Rebruary 9, 1500-December 4, 1500). (d. 1504)

- Adriano Castello (aged ca. 45), Cornetanus [Castellenese da Corneto], Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (created on May 31, 1503; d. 1521) [This was the titular Church held by the former Datary, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Ferrario, who died in July, 1502]. Secretary of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, Adriano was the Pope's secretary of Briefs at the time of his elevation to the cardinalate in 1503, and continued to function as such for some weeks thereafter [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 698, 768, 813; 5, 53; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 3 (May 2, 1503); 7 (May 6, 1503), 29 (May 31, 1503), 44 (June 22, 1503)]. Early in his career he was sent as Papal nuncio to Scotland, and collector of the Peter's Pence in England, 1488. Notary of the Apostolic Camera [Burchard Diarium I, 352 (April 24, 1489)]. Cleric of the Apostolic Camera [Burchard, Diarium II, p. 334 Thuasne (July 31, 1496), p. 349; p. 386 (June 4, 1497)]. He was made a protonotary apostolic on October 14, 1497 [Burchard Diarium II, 410]. On June 4, 1498, he departed Rome as member of a legation to the King of France [Burchard Diarium II, 474]. He participated (as protonotarius et secretarius) in the ceremonies of Christmas Day, 1499, for the beginning of the Jubilee of 1500 [Burchard Diarium II, 502, 602, and 582-602]. Bishop of Hereford, England (Provided February 14, 1502; consecrated May 9, 1502; translated to Bath and Wells, August 2, 1504) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I, 143 and 466-467; Cassan, Lives of the Bishops of Bath and Wells, 331-346]. He had written a book on hunting, which he dedicated to Cardinal Ascanio Maria Sforza. In June, 1503, shortly after his elevation to the Cardinalate, he was in discussions with the Venetian Ambassador Giustiniani to bring about an alliance between Alexander VI and Venice [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 37 (June 10, 1503)]. He supported the candidacy of the French Cardinal Georges d' Amboise (Rouen). But he was reported as ill on August 13, and did not appear at any of the Congregations or at any of the Novendial Masses; he did not attend the Mass of the Holy Spirit on the morning of September 16, but was one of the six cardinals who entered that afternoon [Burchard III, 268].

- Jaime Casanova (aged ca. 67), Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano Rotondo in Monte Coelio. Protonotary Apostolic. Chamberlain of His Holiness (d. 1504)

- Francesco Piccolomini (aged 64), Senensis, son of Nanni Todeschini, the richest man in Siena, and Laodamia Piccolomini, sister of Pius II; he was adopted by Pius. His brother Antonio was married to a daughter of King Ferdinando of Naples (died 1494). Cardinal Francesco was Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. He was Administrator of the diocese of Siena (1460-1503), never having been consecrated bishop, nor even priest, until he became pope. Protector of the Camaldolese. He was also Protector of the Canons Regular of S. Augustine of the Most Holy Savior by 1485 [ Bullarium Canonicorum Regularium Congregationis Sanctissimi Salvatoris (Romae 1733), pp. 102-108, nos. 43-49] He had been Rector of the Marches of Ancona from 1460-1463. He was Vicar of Rome, when Pius II went on Crusade in 1464. He died, as Pius III, on October 18, 1503. Nephew of Pius II. Doctor of Canon Law (Perugia). In June of 1503, in a conversation with the Venetian Orator, he urged Venice to take the lead in expelling the barbarian from Italy, and thereby profit from the discord between the French and the Spanish [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 46-49].

- Raffaele Riario, S. Georgii, Cardinal Deacon of S. Georgio in Velabro, Cardinal Camerlengo. He arrived in Rome on the afternoon of September 9 [Burchard Diarium III, 262].

- Giovanni Colonna (aged 46), son of Antonio Colonna, 2nd Prince of Salerno, Marchese di Cotrone, Signore di Cave, Rocca di Cave, Genazzano, Ciciliano, San Vito, Pisoniano, Olevano, Serrone and Paliano, etc.; and Imperiale, daughter of Stefano Colonna Signore di Palestrina e Bassanello. His brother Prospero Colonna was Duke of Traietto, Count of Fondi, etc. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro (1480-1508). Administrator of the Church of Rieti (1480-1508). Abbot of Subiaco (1492-1508). In February, 1503, he was in Sicily [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 4, 753]. He arrived in Rome in the late afternoon of September 6 [Burchard Diarium III, 260]. He was in the Spanish party [Sigismondo Tizio, in Piccolomini, 112].

- Ascanio Maria Sforza Visconti, (aged 48), son of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan (1401-1466); and Bianca Maria Visconti, illegitimate daughter of Filippo Maria I Visconti, Duke of Milan and Agnese del Majno. Cardinal Ascanio was the younger brother of Ludovico "Il Moro", Duke of Milan and Conte di Pavia (1494-1499). Ascanio was Cardinal Deacon of SS. Vito e Modesto in Macello Martyrum (1484-1505). Legate in Bologna (1490). Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. [Ciaconius-Olduin III, 208]. He had been captured by the French at Milan in 1500, and was being held a prisoner. He was being brought to Rome in the train of Cardinal Georges d'Amboise. On August 4, 1503, Pope Alexander removed his suspension as Vice-Chancellor, at a cost of 10,000 ducats [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 96]. He was, of course, an enemy of the French, the Aragonese of Naples and Cardinal della Rovere [See Sigismondo Tizio, in Piccolomini, 112: Aderat tunc inter patres Ascanius, ut diximus, cardinalis Mediolanensis, Ludovici ducis germanus, e manibus Gallorum sua versutia erutus, Gallorum hostis, qui Mediolani statum recuperare aliquando cogitabat]. He died on May 27, 1505 at the age of fifty. His memorial inscription in S. Maria del Popolo: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 332 no. 1258.

- Giovanni de' Medici [aged 29], son of Lorenzo the Magnificent of Florence. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Dominica (1492-1513). Abbot commendatory of Montecassino (1486-1504) [Bullarium Romanum Turin edition Tomus 5, p. 401 (November 22, 1503)]. Future Pope Leo X. He was an opponent of the French [In the sentence that follows the one in the line just above, Sigismondo Tizio says: Ioannes quoque, Laurentii Medicis filius, ratione Gallorum patria cum fratribus exul, idem cupiebat].

- Alessandro Farnese (aged 35), son of Pier Luigi Farnese and Giovanella Caetani, granddaughter of Ruggero, Grand Chamberlain of the Kingdom of Naples [Romanus]. His sister had been having sexual relations with Pope Alexander VI. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (1493-1534). A student of Pomponio Leti. He had been made Scriptor and Protonotary Apostolic by Innocent VIII. Alexander VI appointed him Treasurer of the Apostolic Camera. Bishop of Montefiascone (1499-1519) [Eubel III, 248 n. 2]. Legatus a latere in Viterbo, 1494 [Bussi, Istoria della città di Viterbo, 285-286]. Legate in the Marches of Ancona, departing Rome on November 26, 1502 [Burchard Diarium III, 224]. Future Pope Paul III.

- Federico Sanseverino (aged 28), fifth son of Roberto (1418-1487) Conte di Caiazzo (1483); Conte di Colorno, Marchese di Castelnuovo Tortonese (1474), Signore di Lugano (1479), etc (whose grandfather Bertrando was Grand Constable of the Kingdom of Naples).; and Elisabetta Montefeltro, illegitimate daughter of Federico III Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. Federico Sanseverino was Cardinal Deacon of S. Teodoro (1492-1513). He was Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Maillezais (Malleacensis) in the Vendée, from 1481 [Eubel II, p. 184], not Maizellais (as in Salvador Miranda) or Marseille (as in G-Catholic) or Malaga (as in Cardella III, p. 243). He was, or became, a mortal enemy of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (Julius II). His connections were French and Milanese (several of his father's titles). His eldest brother, Gianfrancesco, was a general in the armies of the Duke of Milan and of the King of France. The second-oldest brother, Antonio Maria (d. 1497) served in the French army at Monferrato. Another brother Gaspare (Fracassa) was in the service of the Sforza. His fourth brother Galeazzo died in the Battle of Pavia, 1525. Cardinal Federico was a diplomatic agent for Lodovico il Moro, Duke of Milan [Molini, Documenti di storia italiana II, p. 38 (April/May, 1500)]. On May 5, 1503, the Venetian Orator Giustinian reported that Pope Alexander was making Cardinal Sanseverino legate to Bologna pare per raccomandazione del Re di Francia [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 7]; however, on July 19, the Bolognese Orator presented the Pope with a demand that the appointment of Cardinal Sanseverino be cancelled, and Cardinal Loris (Elnensis) be sent instead. Since the French side was not doing well, the Pope was amenable to the Bolognese. The Cardinals in Consistory, however, were in favor of Sanseverino [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 73, 75].

- Giuliano Cesarini. His brother Giovanni was married to Girolama Borgia (1482). Cardinal Deacon of SS. Sergius and Bacchus (1493-1503), Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica Bishop of Ascoli Piceno (1500-1510). Protonotary Apostolic. He died on May 1, 1510.

- Ludovico (Luis) de Aragona, natural son of King Alfonso of Sicily. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (ca. 1497-1519).

- Amanieu d' Albret, son of Alain Comte de Dreux, and Francoise de Brosse; brother of Jean, King of Navarre. Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicolaus in Carcere Tulliano (1500-1520). Sororius of Cesare Borgia. He paid 10,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Ludovicus (Pedro Luis) Borgia(-Llançol), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1500-1511).

- Marco Cornaro, Cornelius, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Porticu (1500-1513). He paid 20,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77]. He was at Padua when he heard of the death of the Pope on August 18; on the evening of the 19th he left for Rome by ship, heading for Pescara [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 65-67], He arrived in Rome on September 1 in the evening [Burchard Diarium III, 256].

- Francisco Lloris (Hiloris), nephew of Cardinal Juan Borja, who had died on August 1, 1503. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nova (1503-1506). Bishop of Elna (1499-1506). Bishop of Terni (1498-1499). Thesaurius Generalis [Ciaconius-Olduin III, 207]. Papal Chamberlain. He died on July 22, 1506. Heluensis.

- Luis Juan del Milan, [Jativa] Hispanus; his mother was Catalina Borja, elder sister of Pope Calixtus III (Borja). Cardinal Priest of SS. Quattuor Coronati (1456-1510). Bishop of Lerida (1459-1510) [España Sagrada 47, 84-87]. Bishop of Segorbe (1453-1459). Canon and Provost of Valencia.

- Raymond Pérault, Gallus (aged 68), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria Nova (1499-1503), at the request of the Emperor Maximilian. Made Legate in Perugia and Lombardy by Alexander VI (1499). Bishop of Gurk (1491-1499), Legate in Germany. Under Julius II he was legate to the Patrimony of S. Peter, and died in Viterbo on September 5, 1505, at around the age of seventy [Bussi, Istoria della città di Viterbo, 292, with his memorial inscription].

- Guillaume Briçonnet, son of Jean Briçonnet, Sieur de Varennes, and Johanna Berthelet; Guillaume's brother Robert was Keeper of the Seal (1491-1493) [A. Tesserau, Histoire de la Grande Chancelerie de France (Paris 1715), 65], and then Guillaume's predecessor as Archbishop of Reims (1493-1497); Robert was Chancellor of France (1493-died June 3, 1497) [Tesserau, 67-71]. Guillaume Briçonnet was Bishop of Saint-Malo (1493-1497), Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana (1495-1514). Archbishop of Reims and Peer of France (1497-1507) [Gallia christiana 9, 144-145]. "Macloviensis" He crowned Louis XII on May 27, 1498.

- Philippe de Luxembourg, son of Thibault of Luxembourg, Lord of Armentiers, Bishop of Le Mans (1465-1476) [Gallia christiana 14, 411-412]. Cardinal Priest of SS. Marcellino e Pietro (1495-1519), Bishop of Le Mans (1476-1507) in succession to his uncle. Bishop of Terouanne (Morinensis) (1498-1516) [Gallia christiana 10, 1569]. Bishop of Arras (1512?) [Gallia christiana 3, 347]

- Tamás Bakózc [Herdouth], Hungarian, Cardinal Priest of S. Martini in Montibus (1500-1521), on the petition of King Vladislav and the Republic of Venice. Archbishop of Strigonia [Esztergom] (1497-1521). Chancellor of the King of Hungary. He had been Private Secretary of Cardinal Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara (who was Administrator of the Diocese of Eger in Hungary, 1497-1520) He had been educated at Bologna and Ferrara. He paid 20,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77].

- Pietro Isvalies, Sicilian, Cardinal Priest of S. Ciriaco in Thermis (1500-1511), Archbishop of Reggio Calabria (1497-1506), consecrated in the Papal Chapel on June 4, 1497, by one of the papal secretaries Bartholomeo Flores, Archbishop of Cosenza. Governor of the City of Messana ( -1497) [Ughelli-Colet Italia sacra 9, 333; recte?]. Governor of the City of Rome, in succession to Bishop John of Ragusa, ca. August 11, 1496 [Burchard Diarium II, p. 335, 356]; John of Ragusa had been named Datary [Burchard Diarium II, p. 362]. When he became Governor, Msgr. Pietro was already Protonotary Apostolic. He paid 7,000 ducats for his red hat [Burchard III, 77]. He was absent from the Curia in August, 1503, as Legate in Hungary [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 125, 135, 140]; he had been appointed on October 5, 1500 [Eubel III, p. 7 n. 4].

- Melchior Cupis von Meckau (aged 62), Cardinal Priest of S. Nicola inter imagines (May 21, 1503-1509). Bishop of Brixen in the Tyrol (1482-1509), with a coajutor from 1501. Provost of Magdeburg and Canon of Brixen. Scriptor litterarum apostolicarum. On October 3 news was received at Venice that the Cardinal of Brixen was going to go to Rome, and that he was going to travel by way of Venice [Diarii di Marino Sanuto 5, 152]. (d. 1509)

- Ippolito d' Este, Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in silice (September 20, 1493—September 3, 1520), Administrator and Archbishop-elect of Milan (1497-1520). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica since September 18,1501 [Burchard Diarium III, p. 163 n. 1; and see 174], in succession to Cardinal Juan Lopez. He was Legate in Bologna. He returned to Rome on December 23, 1501, for the Christmas festivities [Burchard III, 174]. On July 20, 1502, he was given the Church of Capua in commendam, on the death of Cardinal Lopez [Burchard III, 213]. On February 15, 1503, d'Este left Rome for Ferrara, because of a falling out with Cesare Borgia (The Cardinal was apparently having relations with Cesare's sister-in-law, in competition with Cesare himself) [Burchard III, 237: pro eo quod idem Cardinalis diligebat et cognoscebat principissam uxorem fratris dicti ducis, quam etiam ipse dux carnaliter cognoscebat]. He returned to Rome again on October 28, 1503 [Burchard, 291].

Preliminaries

On August 19, 1503, the same day as the body of the pope was being placed on view in Saint Peter's Basilica, sixteen cardinals assembled at the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, a site with both privacy and security, for the First Congregation. They dared not approach the Vatican Basilica or attend the papal funeral for fear of their lives. Cesare Borgia and his men held the Vatican with 12,000 troops [Platina IV, 1], and the Borgo was filled with his soldiers and gentlemen [Giustinian, 122]. Borgia was attempting to negotiate through the Spanish Ambassador and Archbishop della Valle to get control of the Castel St. Angelo, where he would be safe from his enemies. Cardinal Carafa, "come capo del Collegio" [Giustinian, 122] publicized the fact that the cardinals did not intend to go to the Vatican Palace, as was the custom, because of the tumult of the soldiers. The Cardinals included Oliviero Carafa, Jorge da Costa, Girolamo Basso della Rovere, and Antoniotto Pallavicini; Giovanni di San Giorgio, Bernardino Carvajal, Juan de Castro, Jacopo Serra, Francisco Borgia, Juan de Vera, Niccolo Fieschi, Francisco de Sprats (des Prades); Giovanni de' Medici, Federico de Sanseverino, Jaime Casanova, and Amanieu d' Albret. Instead, meeting at the Minerva, they appointed Giovanni, Bishop of Ragusa Governor of the City and broke the lead seals of the late pope, ordering that the Fisherman's Ring should be given to the Datary, Juan Ortega, Bishop of Potenza [Burchard Diarium III, 252], (which was done through Cardinal Casanova). They also ordered an inventory to be made of the pope's property. General opinion, Giustinian reports to Venice, was in favor of Cardinals Carafa and Piccolomini, and then Giorgio Costa and 'Capaze' [Podocatar] (who was a bit indisposed when Giustinian paid a call that day).

On Sunday, the 20th, the Second Congregation took place, with eighteen cardinals in attendance (Domenico Grimani, Giuliano Cesarini, Francisco Lloris, and Francesco Remolino being added; Pallavicini and Castro were absent). There were disorders in the Piazza della Minerva, with mounted horsemen and many other people, led by Micheletti, which caused considerable alarm among the cardinals. Cardinal Juan Vera (Salerno) went out to try to disperse them, but it was the arrival Bishop of Ragusa and the Caporegioni and people of Rome (who hated Cesare and the Spanish) that finally restored order. Both the French Ambassador and the Venetian offered the cardinals assurance (without, as Giustinian puts it, descending into any particulars) of their support for a free and independent conclave [Giustinian, 129-130].

On the 21st, Cardinal Ludovico Podocatar made his appearance. In the morning, Giustinian had an interview with Cardinal Carafa, "come decano e capo del Collegio" [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 135-136], who pressured him to enter into specifics about the protection he had offered for the security and independence of the Conclave. The Dean complained that they were hemmed in by the French on the one side and the Spanish on the other, and that the Colonna had made common cause with Duke Cesare and the Spanish. He told Giustinian as well that the Provost of the Castel S. Angelo, Jacopo de Rochemora, Bishop of Nicastro (Gregorovius, 4), had sworn an oath of loyalty to the College of Cardinals, and that he would receive one hundred soldiers loyal to the College into the Castel. But, unless the Papal Palace and indeed the entire Borgo were cleared of all men-at-arms, the Cardinals would not go to the Papal Palace. Giustinian, who had even been addressed by his praenomen by the Cardinal in his anxiety, could only promise to consult the Doge as quickly as possible, but that he had nothing more specific to offer. In a letter written only two hours later, Giustinian reports to the Doge that he had heard that eleven cardinals, in the presence of Duke Caesare, had sworn to elect no other person as pope but the Cardinal of Salerno, Juan Vera of Valencia. He also had intelligence that Duke Caesare intended to prevent the appearance of the two Riarios, and had posted Spanish galleys at all the ports by which they might arrive (Giustinian, 138). It was apparent that the Spanish Ambassador was working with Duke Cesare to have a Spanish pope (also Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 144). In his third letter of the day, written after sunset, Giustinian (140) reports that Cardinal Carafa had let him know that Cardinal Pallavicini, who was working on both the French and the Italians with a view toward his own candidacy for the papacy, had informed the Dean, in the name of the Palatine Cardinals, that they wanted the Conclave to be held either at the Minerva or at S. Marco, or at some other secure place.

On August 22, Cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini of Siena made his appearance at the Fourth Congregation. His brother, Iacobus, had travelled down from Siena immediately on the news of the death of Alexander VI, intent on managing the campaign for the election of his brother [Sigismondo Tizio, in Piccolomini, p. 110]: At Iacobus, negociis ceteris sepositis, Romam propere concessit cepitque tunc singulos patres compellare, pro sua fratrisque re laborare ac esse sollicitus. Siena was in a fever of expectation that Cardinal Francesco would be elected pope. It was voted unanimously in the Congregation to hold the conclave in the Castel St. Angelo, with the hope of opening the Conclave on the 28th. That evening Prospero Colonna entered the city with 100 of his cavalry, even though the Sacred College had begged him not to come, but to leave the Conclave undisturbed. They made a similar appeal to the Orsini, which was also ignored (Burchard, 246, 249; Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 142).

On Wednesday the 23rd, the Fifth Congregation met at the house of Cardinal Carafa, the Dean of the Sacred College; which was apparently more secure than the Minerva. Lorenzo Cibo, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina, was present, along with Giovanni Ferrero, Archbishop of Bologna. The cardinals reaffirmed their wish to hold the Conclave at the Castel St. Angelo, but that it would have to be deferred for ten days. That evening Ludovico de Piliano and Fabio Orsini entered the city with 200 cavalary and about 1000 infantry by way of the Porta S. Pancrazii (Giustinian, 147, makes it 400 cavalry and 1500 infantry), during which they killed three innocent Spaniards whom they had come upon; they also sacked around 100 houses near the palace of the Vice-Chancellor (Cardinal Ascanio Sforza Visconti, who was still with the advancing French army, having been released from captivity on orders of the French King).

On the 24th, the Sixth Congregation took place, again at the house of Cardinal Carafa. . Giustinian reports (149), "El remor de la zente Orsini de heri sera ha messo in spavento li Duchesini, i quali questa notte se hanno fortificato in Borgo et in Palazzo più de solito, hanno tirato la cadena, e non lassano passar alcuno di lì a cavallo nè a pe con arme, nè anche lassano che alcuno di questi di là passino di qua." He notes that the Colonna would be supplying 3000 men that night to defend the Spaniards. Gregorovius [p.3, n. 2] cites a letter written by Cardinal Francisco Borgia on August 25, estimating Caesare's forces at 600 men-at-arms, 1000 light cavalry, and 6000 infantry. Borgia was trying to encourage the people of Sermoneta, where a revolt had broken out, to remain loyal to Cesare and the Colonna: "vagliono opprimere questi Orsini".

On the 25th, at the Seventh Congregation, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese was present for the first time [Burchard Diarium III, 249]. The Cardinals met with the four Ambassadors, Spanish, French, Imperial and Venetian, to see what could be done to make Rome safe enough for a conclave [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 152-154]. They all complained about other people being at fault. Giustinian takes credit for making it clear that it was Duke Cesare who had to do something, as Gonfalonier of the Church in place of the Orsini, to make the city secure, and that would require his leaving it. In the evening the ambassadors met with Duke Cesare and, with Giustinian acting as their spokesman, made their case that the Duke could solve the problem with his departure [Giustinian, 154-157]. The French and Spanish ambassadors, however, both interested in having Cesare on their side, were agreeable to letting Cesare seek refuge in the Castel S. Angelo, garrisoning it with his own troops.

On the 26th, at the Eighth Congregation, there were twenty-one cardinals; the Cardinal of Perugia (Francesco Remolino, Archbishop of Sorrento, called Sorelmo by Sanuto) having arrived. Late in the day the four ambassadors went to Cardinal Carafa's house and made their report of their interview with Cesare Borgia, that the Duke had to leave Rome and seek security either at Cività Castellana or some other fortress of the Colonna [Giustinian, 158-159].

On Sunday, the 27th, an attack was made by the Orsini, led by Prince Fabio, on some light cavalry of the Duke, among whom was the brother of Cardinal Remolino, and Remolino was killed [Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian II, 160].

On Monday the 28th, the Ninth Congregation took place at Carafa's house, and voted to send four cardinals to the Provost of St. Angelo, requesting him to vacate the fortress so that it could be used for the Conclave. He refused, on the grounds that he was sworn to hand it over only to the new pope. [Giustinian, 133 and 134-135, reports similar remarks made by the Provost on the 20th]. On the 30th the Tenth Congregation took place with eighteen cardinals present; that evening Francesco Soderini, the Cardinal of Volterra was present for the first time. In a letter of the 31st [Petruccelli, 443], Beltrando wrote to the Duke of Ferrara that he had spoken with Cardinal Sanseverino, who said he had demonstrated to the French that their demand to make Amboise pope was impossible. If the College were free in its proceedings, he said, an Italian pope was their preference, and Podocatar, Carafa, Pallavicini and Piccolomini were in the running.

At the Eleventh Congregation, on September 1, an agreement was finally reached with Duke Cesare to leave the city, and the Duke was pleased to swear the oath. A treaty had been struck between Cesare and the French, negotiated through Cardinal Sanseverino and the French Ambassador, Grammont. Cardinal Marco Cornaro arrived from Venice that evening. Sanseverino had the permission of Duke Cesare to procure the votes of the Spanish cardinals for the election of Cardinal Carafa [Petruccelli, 444].

On Saturday, September 2, Cesare finally left, carried out on a litter, followed by Cardinal Sanseverino. However, Odoardo Bugliotti, valet of King Louis XII of France, arrived in Rome, with money to make Cardinal Georges d' Amboise pope. Next day Giustinian (175) was shown a letter by Cardinal Carafa, in which the King wrote in his own hand that each cardinal would gratify him if he voted for the Cardinal of Rouen; various incentives were apparently mentioned. Various negative possibilities were not mentioned, though a French army encamped at Nepi (whither Duke Cesare had fled) was in everyone's mind. According to the Florentine envoy in France, Nasi [Petruccelli, 445], King Louis had also remarked that if Juan Vera, Cardinal of Salerno, were elected, there would certainly be a schism.

On September 3, the funeral ceremony for the late pope was announced for the next day, and that Msgr Ottaviano Archimboldi, Protonotary Apostolic, would deliver the Funeral Oration; likewise it was determined that the Conclave would be held at the Vatican Palace. The Cardinal of S. Pietro in Vincoli (Giuliano della Rovere) and Cardinal Cumanus (Antonio Trivulzio) arrived in Rome (Burchard, 257). Giustinian had a private meeting with Della Rovere, and was not reassured by his platitudes. During the reign of Pope Alexander, della Rovere had quarreled with the pope on three occasions, requiring his withdrawal from Rome; in exile as Legate in Avignon, he assisted King Charles VIII of France in his Italian adventures (1494-1496) and, after his death, King Louis XII as well (1499). He and his Riario cousins were looking for vengeance on Cesare. Only with Cesare gone would Rome be safe for them, though Cesare, to everyone's shock and annoyance, was now apparently treating successfully with the French, again through Cardinal Sanseverino. (The text of the treaty between Cesare and the French is given in Giustinian, 462-464. Cesare agreed to detach himself completely from the troops of the King of Spain and put himself and all his forces under the command of the French in the matter of the Kingdom of Naples, "et faire comme bon serviteur, vassail, et chevalier de son ordre doit faire" )

Novendiales

The first of the novendiales, long delayed by the danger, finally took place on Monday, September 4. Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Antoniotto Pallavicini, with twenty other cardinals in attendance, including Giovanni Colonna, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro (Burchard, 258). Burchard repeatedly had trouble getting cardinals to agree to be the celebrant of the Mass. Perhaps there was a fear on their part of being poisoned.

In an interview with Giustinian on September 5 (Dispacci II, 180), Cardinal della Rovere, who had arrived in Rome on the previous day, made a remarkable statement: "Vedete, Domine Orator, niun' altra causa ne potria far inclinar la mente a voler Papa Roano, ch' el timor di non poter star sicuri in Roma, perche semo certi che, essendo lui Papa, la Corte si transferira in Franza." Assured, of course, that Giustinian would spread about this specter of the Papacy returning to France and another Babylonian Captivity, della Rovere was indicating why the new pope had to be Italian, and why he, who was not (as many thought) a tool of the French, would be the best leader in the crisis.

On the 9th, after lunch, the Cardinal Chamberlain, Raffaele Riario, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio ad Velum aureum, entered Rome and took up residence in his palace next to S. Lorenzo in Damaso. The French army was denied access to the bridges across the Tiber in Roman territory. On the evening of the 10th of September, Cardinals Georges d' Amboise (Rouen), the Vice-Chancellor Ascanio Sforza Visconti (son of the Duke of Milan), and Luis de Aragón of Naples entered the city (Burchard, 262). Their arrival is also mentioned in a dispatch to Venice, with the note that the Cardinals did not intend to enter into conclave "finl non ensa francesi e spagnoli di il via." The report also states that it was unknown who would be made pope, but four cardinals were being mentioned: Della Rovere, Piccolomini, Carafa, and 'Capaze' [Podocathar]; the Venetians had decided to support Della Rovere and Carafa (Sanuto, 85).

September 12 was the last of the novendiales, and a meeting of the cardinals in the sacristy after Mass decided that the Conclave would begin on the next day. Three ambassadors were selected by the Cardinals to guard the access roads to the Conclave, the Imperial, English and Venetian orators; the Venetian orator refused the honor, on the grounds that "era dolor e non armigero" (Sanuto, 86). Burchard, the Papal Master of Ceremonies, mentions that he had to rearrange the conclave cells of a number of cardinals, in particular Cardinals Antoniotto Pallavicini and Juan Castellar, because Pallavicini, who expected to be made pope, did not want to room next to Francesco Piccolomini (who, as events turned out, was made pope). A list of all the thirty-seven assignments is provided by Burchard (263-264), and a similar list appears in the Diary of Marino Sanuto, the Senator of Venice (col. 103). In a report to the Marquess of Mantua (Pastor VI, 193 and 619), his ambassador, Ghivizano, wrote, "Neither Amboise, nor Guiliano, nor Carafa, nor Riario will be pope; Podocathar, Piccolomini or Pallavicino have the best chance for they are favored by the Spanish."

Conclave

On Saturday, September 16, 1503, the Conclave finally opened, with the singing of the Mass of the Holy Spirit by the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino Carvajal (Burchard, 267; Panvinio, 357, states that it was the Dean, Cardinal Carafa—only his guess). The Oration de eligendo pontifice was given by Alexius Celadoni, Bishop of Gallipoli in the Kingdom of Naples [Eubel II, p. 25 n.2; p. 157]. Thirty-one cardinals entered the Vatican Palace, out of a total number of forty-six (Burchard provides a list, p. 267-268, as does Marino Sanuto, cols. 100-102); after lunch they were joined by the other six (including. finally, Cardinal Adriano Castello). The names of the conclavists are also given in full by Burchard [pp. 268-271]. He notes that there had already been politicking among the cardinals. Carafa, Giuliano della Rovere and Girolamo Basso della Rovere and several others "conjurarunt inter se de non faciendo papam, vel dando vota inter se." [Burchard, 265]

On Monday the 18th all of the cardinals were present at Mass except Casanova, who was ill. After Mass there was a meeting at which the Electoral Capitulations began to be worked on, much as they had been for Innocent VIII's election. Sigismondo Tizio, in his History of Siena [Piccolomini, p. 111], reported that his informants stated that Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini had been instrumental in their formulation:

Igitur patres in conclavi, dominica die (Sunday, September 17) missa de more celebrata, die lune (Monday, September 18) circa res fidei christiane atque universalis ecclesie intenti, ut fit, privilegia cardinalium expromere aliaque capitula, ut fieri solet, unanimes servanda, vovenda, iuranda; dieque mercurii (Tuesday, September 19) suis solemnitatibus edidere. Inter cetera autem statuunt creari cardinales ab eligendo numquam licere, ni prius illorum cetus ac numerus citra viginti quatuor decrescendo retrocedendoque, illis obeuntibus, revertatur. Cuius rei Franciscus Picolhomineus cardinalis, in suorum iacturam, auctor fuisse ferebatur; consulitque quinternos cum inscriptis capitulis novem fiendos, ut penes cardinales plures essent, ne quod apud Alexandrum gestum fuerat, ultra accideret. Ille enim tres qui capitula iurata continebant, ad manus suas callide pervenisse curaverat, ut nullo deinceps tempore secum conveneta valerent cardinales ostendere et fiendis contradicere.

Giustinian (p. 198) reported to Venice in a letter of the 19th that the pratticà appeared to be going in favor of the Cardinal of Siena (Piccolomini), though Rouen was saying that he would be pope. On Wednesday the 20th, all the cardinals were present for Mass except Casanova and Adriano Castello de Corneto. The capitulations were finalized and given to secretaries to be copied and distributed. On Thursday the 21st, Cardinal Carvajal said the Mass; Casanova was still absent. Giustinian (199) reported again that it seemed Cardinal Piccolomini would be pope. Afterwards the cardinals met to revise the capitulations, an operation that took all the rest of the day and part of the evening. The manuscript Vaticanus Latinus 8685 contains a copy of the Caputulations [Vincenzo Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 244]. A scrutiny was held on Thursday, the 21st [Burchard, 273-276; Marino Sanuto 5, 93-94, reporting only the top eight recipients; Sigismondo Tizio, in Piccolomini, 112]. It was a "preference" poll, in which the cardinals listed their favorite candidates; as many as five names were submitted by a single cardinal. The results showed support as follows:

| Cardinal | Support |

Support by preference |

|---|---|---|

| Oliviero Carafa | 14 |

12 1st / 2 2nd / 0 3rd / 0 4th / 0 5th |

| Giuliano Della Rovere | 15 |

6 / 8 / - / - / - |

| Jorge Costa | 7 |

2 / 3 / 2 / - / - |

| Girolamo Basso della Rovere | 1 |

1 / - / - / - / - |

| Antoniotto Pallavicini | 10 |

3 / 4 / 3 / - / - |

| Giovanni di San Giorgio | 8 |

1 / 3 / 2 / 2 / - |

| Bernardino Lopez de Carvajal | 12 |

7 / 2 / 2 / 1 / - |

| Domenico Grimani | 1 |

- / 1 / - / - / - |

| Georges d' Amboise | 13 |

5 / 1 / 4 / 3 / - |

| Jaime Serra | 5 |

- / - / 4 / - / - |

| Francisco Borgia | 5 |

- / 1 / 2 / 1 / 1 |

| Juan de Castro | 11 |

- / 8 / 2 / 1 / - |

| Juan de Vera | 5 |

- / - / 2 / 3 / - |

| Ludovico Podocatar | 2 |

- / - / 2 / - / - |

| Antonio Trivulzio | 1 |

- / - / - / 1 / - |

| Francisco Desprats | 1 |

- / - / 1 / - / - |

| Francesco Piccolomini | 4 |

- / 1 / - / 2 / 1 |

The detailed statistics indicate that the real support was with Carafa, then Della Rovere, Carvajal and Pallavicini, but that none of them was anywhere near the 25 votes needed to elect. It appears, however, that two of them (Carafa and Della Rovere) had sufficient support, if it was firm support, to prevent the election of an enemy, and it may noted that those who placed Carafa's name first usually placed della Rovere's name second, and vice-versa. Those who voted for Carvajal usually voted for Castro as their second choice. Piccolomini was the only Cardinal Deacon who had received any votes at all. According to Sigismondo Tizio, his support came from Giovanni Antonio de S. Giorgio (the cardinal Archpriest); Giuliano Cesarini (a cardinal deacon); Raffaello Riario (the Cardinal Camerlengo); and Antoniotto Pallavicini (Cardinal Bishop of Albano). Tizio also reports Burchard's numbers on the leaders (though he writes "Columnensis" for "Carthaginiensis", Carvajal). In truth, the first vote constituted a series of compliments and fulfillments of promises, sometimes casually given, to vote for someone for pope. The remarkable thing is that Georges d' Amboise had nowhere near the support that the French thought he had or deserved.

Giustinian wrote to the Doge of Venice (Dispacci II, 199-202) about the scrutiny, confirming in part Burchard's statistics:

Avanti che si scortiniasse, Santa Priseida [Pallavicini] se reputiva Papa col favor de Spagnoli, et el cardinal de Roano [Amboise] fo desconzato per poera de San Piero ad Vincula [Della Rovere], e lui se tirò fin a ventidue voti, et avanti che se facesse el scortinio, Ascanio el desconzò. Tutti poi d' accordo declinoro in questo che è fatto, el qual non vose esser cortiniato el zuoba [giovedi] del 21 del presente, che fo el primo scortinio, benchè fin allora le cose fosseno assettate, nel qual scortinio San Piero ad Vincula ebbe 15 voti, Napoli 14, Roan 13, et Agrigentino [Castro] 13, li altri de li in zoso; e visto che in niun de altri la cosa poteva reussir, el cardinal de Roan ha voluto, non possendo lui esser Papa, non se veder questo altro scorno ch' el se facesse uno contra el voler suo, e, come prudente, seguito el corso dell' acqua . . . Ma sopra tutti el cardinal de Roano si tiene offeso dal Duca di Valenza, contra el qual el disse parole di mala sorte, dal qual el se reputa tradito per non aver mai potuto, per partito che l' abi fatto, piegar pur un Spagnolo dalla sua ...

After dinner the cardinals got together in groups to discuss the candidates. One group, which included Georges d' Amboise, Ascanio Sforza, and Francesco Soderini, decided on Cardinal Piccolomini, whom they had heard to say that he would have Georges and Ascanio resident at the papal palace (in other words that they would be 'Palatine Cardinals', principal advisors and administrators for the pope) (Burchard, 276). Blatant self-interest cannot be ignored in calculating the hopes and fantasies of cardinals. But the notion that the First Minister of the King of France would become a principal papal administrator is beyond credibility. And Burchard is surely wrong in calculating the position of Cardinal Ascanio.

The French party was stoutly resisted by the Spanish party, which had the larger number of supporters. The latter included Ascanio Sforza, whose family were hostile to the French, who were pursuing a claim to the Duchy of Milan, which would climax in the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Giovanni de' Medici was also supporting the Spanish interest, since the French had been responsible for driving his brother out of the city of Florence. They, along with Cardinal Colonna (? or Carvajal), were campaigning in favor of Cardinal Piccolomini, whose family had been in high favor with Ferdinand I of Naples (whose bastard daughter, Maria, had married Antonio Piccolomini, Cardinal Francesco's brother) [Sanuto 5, 93: a letter of Antonio di Bibiena to his brother Piero in Venice]. Cardinal Francesco had been personally insulted by King Charles VIII, when, during an embassy to the French king in 1494, he was sent away from the presence of the King without being heard. Tizio (in Piccolomini, p. 113) remarks that the Cardinal's brother advised him to vote for Giuliano della Rovere, nephew of Pope Sixtus IV and Bishop of Ostia. Cardinal Francesco flatly refused. The politicking went on into the night. When the Spanish leaders believed that they had reached the required majority, they repaired to Cardinal Piccolomini's cell. When the French heard the news, they quickly capitulated, knowing that it was more in their interest to be on the side of the winner, rather than to obstruct him in the next scrutiny. That night there was much coming and going of persons and messages. Even Burchard was awakened by a message from the Sacristan, alerting him to what was going on, and that Cardinal Piccolomini was being heavily touted as the next pope.

Election of Cardinal Piccolomini

On September 22, Giovanni Burchard himself offered the Mass of the Holy Spirit. When the cardinals had settled down, Burchard asked Cardinal d' Amboise (Rouen) whether they were agreeable that the election should take place through the Holy Spirit (that is, by acclamation or adoration). Burchard understood that the consultations during the night had produced a likely winner. Cardinal d' Amboise, however, replied that even a single negative voice would invalidate the election. In the balloting that followed, only five of the thirty-seven ballots had not put Piccolomini's name first, four of them listing Georges d' Amboise as their first candidate, and one listing Carafa. Cardinal Piccolomini (Senensis) finally received all the votes except his own (which went for Carafa and secondly for San Giorgio). The Cardinal of Siena was declared elected (Burchard, 276-277). He was 64 years of age. The Papal Throne had been vacant for thirty four days.

On Thursday the 28th, the new Pope informed Giovanni Burchard that he wished to be ordained a priest on Saturday and consecrated a bishop on Sunday, by the Cardinal of St. Petri ad Vincula (Rovere), assisted by Adello Piccolomini, Bishop of Sovana, and Frencesco Erulli, Bishop of Spoleto. and so Burchard informed Cardinal della Rovere [Burchard Diarium III, 280].

Cardinal Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini was ordained a priest on September 30, and consecrated bishop on October 1. He was crowned as Pope Pius III on October 8 (Burchard, 282-284), on the steps in front of the Vatican Basilica by the new Cardinal Protodeacon, Raffaele Riario. Two cardinals, Lorenzo Cibo, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina, and Jaime Casanova, were ill and could not attend. During the opening procession into the Basilica for Mass, Msgr. Burchard performed the ceremony of the burning of the flax with the reminder, "Sic transit gloria mundi." [Burchard Diarium III, 283].

The Pope never took possession of the Lateran Basilica.

Pope Pius III reigned for twenty-six days, and died on October 18, 1503.

Bibliography

L. Thuasne (editor), Johannis Burchardi Argentinensis . . . Diarium sive Rerum Urbanum commentarii Volume III (Paris 1883) pp 238-315 [There is a gap in the manuscripts between February 22 and August 12, 1503]. Marino Sanuto (ed. Federico Stefani), I diarii di Marino Sanuto Tomo V (Venezia 1881). Bartolommeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis Pontificum Romanorum...que ad Paulum II Venetum ... doctissimarumque annotationum Onuphrii Panvinii (Cologne: apud Maternum Cholinum 1568), 562-565. Bartolommeo Platina ed altri autori, Storia delle vite de' pontifici Tomo Quarto ( Venezia: Domenico Ferrarin 1765). Onuphrio Panvinio, Epitome Pontificum Romanorum a S. Petro usque ad Paulum IIII. Gestorum (videlicet) electionisque singulorum & Conclavium compendiaria narratio (Venice: Jacob Strada 1557). Tomaso Tomasi, La vita di Cesare Borgia detto poi il Duca Valentino (Monte Chiaro: Vero 1655). Pasquale Villari (editor), Dispacci di Antonio Giustinian Ambasciatore Veneto in Roma dal 1502 al 1505 Volume II (Firenze 1876). Henri de l' Épinois, "Le Pape Alexandre VI," Revue des questions historiques 29 (1881), 358-427. Sigismundo Tizio: Paolo Piccolomini, "Il pontificato di Pio III, secondo la testimonianza di una fonte contemporanea," Archivio storico italiano 32 (1903),102-138.

F. Petruccelli della Gattina, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves Volume I (Paris 1864) 435-456 [contains translations of the dispatches of the ambassador of Modena. Beltrando Costabili]. Gaetano Moroni Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 36 (Venezia 1846) 6. Mandell Creighton, A History of the Papacy Volume IV: The Italian Princes: 1464-1518 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin 1887). Ludwig Pastor, The History of the Popes (edited R. K. Kerr) second edition Volume 5 (London: Kegan Paul 1902) 318-321; 375-390. Ferdinand Gregorovius, The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 8 part 1 [Book XIV, Chapter 1] (London 1902) 1-15.

Valeria Novembri and Carlo Prezzolini (editors), Francesco Tedeschini Piccolomini: Papa Pio III: Atti della Giornata di studi, Sarteano, 13 dicembre 2003 (Le Balze 2005).

On Cardinal Riario: Angelo Poliziano, "La congiura de' Pazzi," Prose volgari inedite et poesie latine e greche edite e inedite (edited by Isidoro del Lungo) (Firenze 1867), p. 94. Niccolò Machiavelli, History of Florence Book VIII, chapter 1. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica 57 (Venezia 1852). Charles Berton, Dictionnaire des cardinaux (1857) p. 1445. Erich Frantz, Sixtus IV und die Republik Florenz (Regensburg 1880) 197-230, especially 207 (highly favorable to Sixtus and the Riarios).

On Cardinal Caraffa, the Dean: Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa Tomo Terzo (Roma 1793) 159-163.

On Cardinal Georges d' Amboise, see: Charles Berton, Dictionnaire des cardinaux (1857), columns 234-242. Louis Le Gendre, Vie du Cardinal d' Amboise, premier ministre de Louis XII (Rouen: Robert Machuel 1726).

On Cardinal Adriano da Corneto: William Maziere Brady, Anglo-Roman Papers (London: Alexander Gardner 1890), 11-29.