Preface

This is the age of youth. Let everything not strictly modern and up to date be done away with. Tear down all our old land marks to make way for progress. Discard anything which bears a date mark more than a year old. Speed is the word now.

Gone are the days when our eyes would widen and astonished exclamations greet the news that Uncle John had taken his new car, and with a stiff tail wind and a down hill drag, actually done fifty two M.P.H.

In fact most of the landmarks of that era have vanished and are forgotten.

I am not one to deny the benefits of our modern age, but having had the privilege of living in "the dark ages", as the children put it, I regret the passing of old landmarks and friends both mechanical and human.

Bearing in mind the fate of the passenger pigeon which, beside being extinct numerically, has slipped from the memory of most of us, and the similar path which "Old Dobbin" is taking, it has occurred to me more and more often of late that I should set down, before time has dimmed my memory too greatly, the chronicle of an old and valued mechanical friend.

Chapter 1

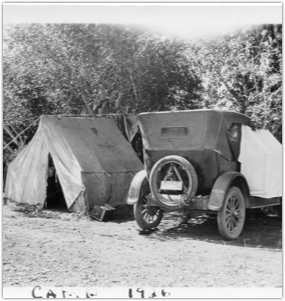

The tale begins in the then-small city of San Diego, California, in the year 1917. My father had been elevated to the position of shop foreman in the carpet department of one of the city's larger furniture stores, and as his salary had been increased to the imposing figure of $25.00 a week, the family's hope of acquiring an automobile naturally rose.

Since the San Diego back country had a wealth of interesting possibilities for an adventurous clan, and as we boasted reasonably good roads--mostly well-graded decomposed granite--and only an average number of washboards per mile, the idea of mechanized transportation simply would not stay in the background. Every mealtime and evening the subject would pop up. Strange as it may seem the matter of finances was the principal holdup, as we were all agreed on the advisability of spending our spare time patching tubes, and washing grease from our hands for the privilege of hitting the open road.

Suddenly, after a number of weeks of unfruitful talking and planning came the big "break."

Dad came home one evening looking like the cat that swallowed the canary, and we knew something was up, but since he delighted in keeping us in suspense, it was not till supper was nearly over that he broke it to us. Even then he dragged it out with a long story of how the management of the store was unhappy with the transportation arrangements for the carpet department. The store had two regular delivery trucks, but when they were down to National City or out to La Jolla, [that would be when] Dad needed a roll of battleship linoleum delivered to Pine Hills on a rush job. And, of course, most of the mechanics had to depend on the street car, or if the job was a good distance away, on the train. These factors made the labor cost out of proportion to the job value, and so The Great Decision. At least to us it was. "

Herman told me, this evening, this evening, that if I would buy [an auto] and use it for the shop the store would furnish all the gas and oil and allow me $25.00 a month for tires and upkeep.

Herman told me, this evening, this evening, that if I would buy [an auto] and use it for the shop the store would furnish all the gas and oil and allow me $25.00 a month for tires and upkeep.

That was "it.! You never heard so much noise from one small family of four people. If we had had a tape recorder then the tape could have been used for sound effects for a mob scene on T.V.

Within the next few minutes more plans for the financing of our automobile were proposed and discarded than the United States Congress has considered for the financing of the world, but in the end Dad and Mother, disregarding the contributions of my sister and myself, figured out a way to juggle the family budget, thus launching us on the series of incidents and adventures which follow.

Of course having been an avid motor-car fan ever since I saw my first auto, I knew exactly the car and model we should acquire, disregarding, of course, the initial cost and upkeep.

A Winton Six was my first choice, but a Packard would be a good substitute. Still on thinking it over I decided they were both out of our class, and came down to earth, deciding on a Buick. A Buick Four touring would just fill the bill.

It was, to put it mildly, quite a blow to my judgment and pride when Dad quietly announced, that since he was going to have to pay for it, and work to keep it going, our first car would be a Ford. A used one too, mind you.

After digging myself out of the ruins of my dreams of grandeur I finally convinced myself that even a used Ford was better than no car, and how right I turned out to be!

At the time I was attending high school, and was not permitted to absent myself to participate in the search for a suitable car, so I had not even had a peek at the job Dad picked out, as the family eagerly awaited the triumphant arrival that late summer evening in 1917.

At the time we thought Dad should be coming home we lined the rail, so to speak, and in that first glimpse, with the sun shining on the shiny baked enamel body, the polished brass radiator and the newly painted top "The Car" looked like a million dollars to us.

As he proudly wheeled into the driveway from Daley Ave., Dad experienced one of the few high spots in his life, and he sat there, monarch of all he surveyed, as we swarmed over, under, around and into the New Car.

After the furor had subsided a bit and we had thrilled to the smooth purr of the motor, punched the cushions, checked the tires, exclaimed over how good the paint looked, we quieted down enough to take a trial spin, and then we knew Dad surely had a bargain. It was a wonderful car.

As the primary purpose of the Car was for Dad's work and, as without the work clause we would have had no car, I missed the first weekend trip. Dad had to take a roll of linoleum and tools to lay it with up to Pine Hills on Sunday. So there was only room left for him and Mother. They left about five o'clock in the morning and for me, that was one of the longest days of my life.

By five in the afternoon, when they should have been home, I began to get worried. The road to Pine Hills, near Julian, led over several pretty stiff grades for those days, and as two or three cars had gone over the edge recently I was picturing Dad and Mother at the bottom of the canyon, a picture which became more and more vivid as the hours dragged on. Seven, eight and nine--and finally a little after ten I heard what sounded something like a man wheeling broken bottles and old stove lids in an iron-wheeled cart over cobblestones coming down the street. This terrific commotion turned in our driveway and I knew then that they were dragging the mangled remains home.

When I forced myself to open the door and look everything looked normal. But on a second look I saw that while the car had not gone over the cliff and Dad and Mother were all in one piece, the rear end did sag and the car seemed rather tired-looking. A closer inspection showed three bare rims, and Dad said "Something's wrong with the differential." What an understatement that turned out to be, as we gathered tools, jacks, two-by-fours and blocks of wood the next evening and went to work. When we had the rear end disconnected from the car and spread papers and what have you on the ground, we loosened the bolts holding the differential housing together, and Brother!! The whole rear end dropped out in pieces about the size of a walnut. Pieces of gears, bearings, housings, washers and grease gave some idea of what caused the noise on the previous night. Right then we knew if a Ford could actually run with that mess for a rear end, nothing could ever stop us from getting home from a trip. While it was terrifically disheartening to look at the remains of what had once been a transmission unit, it gave us that confidence in our car which enabled us to take trips and come back again, which to the average motorist were impossible.

Up to this time neither Dad or I had ever had occasion to even see what the inside of a car's rear end looked like, and the picture in the parts and instructions books gave us very little help. In fact, they did more harm than good at that time, as they made the job seem worse than it even was.

Dad had, over the years, accumulated a few wrenches and tools suitable for the repair of bicycles, kitchen faucets, and the like, but we had no idea of the number and variety of wrenches and tools necessary to repair a car, so in spite of the instructions we started the job very inadequately equipped. Also due to the fact that we had never seen the insides of the critter, naturally we forgot some of the necessary parts. To anyone reading this case history that may not seem very important, but remember, we had only ONE car then, and it was temporarily indisposed, necessitating a six-block walk to the car line, and then when the car came along, a fifteen or twenty minute ride to the nearest Ford agency, and a few minutes spent trying to make the parts man understand what it was that we were in need of. Then with all this accomplished, the return trip--and better than an hour had been lost. Multiply this by six or seven, and you have some idea of the sped with which we were proceeding.

All this lost motion due to parts deficiency was as nothing to what overtook us when we started to put her together. Oh me! Oh my!, as Tugboat Annie would say. No one who has not had that inexpressible experience can know how many times it is possible to put so simple a thing as a Model T rear end together wrong. But it can be done. We did it. First we could not get the pinion gears off the axle shaft. Then the combination of thrust washer was wrong, and the differential spider assembly would go together backwards but would not run.

At last, due no doubt to the intervention of divine providence, we got it assembled and back in the car, and I doubt if any father and son combination ever were prouder of an achievement.

That rear end job was the beginning of an education and the start of a collectors career in accumulating wrenches, tools and parts.

Oscar

Oscar, when he came to us, was a youth with a past. Not a lurid past, but nevertheless he was well traveled and sophisticated. His appearance was, shall we say, sharp. Well brushed and polished, he looked very capable and efficient. How deceiving can looks be? Shortly after he adopted us he suffered a complete breakdown. I said adopted advisedly, as the papers cost Dad three hundred and twenty five dollars. No sales tax then.

This adoption was not completed without due process and consideration. Consideration mainly of the three hundred and twenty five dollars which at the time was more than a considerable sum, and nearly spoiled at the very beginning what turned out to be a beautiful friendship. This friendship grew and endured three good years and bad, fair weather and foul, and I mean there was plenty of foul weather and bad years, until Oscar attained a ripe old age. He was a faithful friend and traveling companion and while at times he had some of the characteristics of that venerated animal known as the army mule, the general relationship was extremely pleasant.

To go back a bit, at the time the adoption was considered we felt it necessary to inquire into the past of Oscar and learned that he first saw the light of day quite early in 1916, was well dispositioned, and as we said before, well traveled; to be exact, about one hundred thousand long and weary miles. To hold a little more closely to the truth, we did not find out exactly the distance he had traveled until after he joined the family, and to tell the truth we always thought his travels had some direct bearing on his breakdown.

Further questioning disclosed the fact that he came from a family named Ford. When the question of adoption had been taken care of it was necessary, of course, to provide adequate quarters for our new friend. Since at the time our domicile consisted of a one-story, flat roofed, up-and-down board California house about sixteen feet wide and thirty feet long, with a six foot jog in one long side, the question was solved by extending the jog to form a nook eight feet wide and continuing the flat roof to cover the area, thereby completing, with the addition of lattices on the sides, the first car port to my knowledge.

It seemed quite acceptable to Oscar and remained his home for several years.

Another Version

The addition to the family of Oscar was made possible only by means of a plan whereby he was to serve as Dad's transportation to and from the daily round of toil, for a consideration, of course. This plan kept him [Oscar] away from home six days a week and so it was not until the first week end that we were able to really get acquainted.

It was on this first weekend as, as we were carefully washing and polishing his shining black enamel and gleaming brass that we noticed the first symptom of that coming breakdown. Dad and I had moved him back out of the carport for the wash job and I noticed a small pool of oil where his middle stood. "Hey Dad, what's this from?" I queried. Dad rubbed his chin a minute. "Well," he said, "looks like he had too much mineral oil--goes pretty fast you know." That explanation didn't quite satisfy, so we took the floor boards out and the hood off and looked. We might just as well have left them on, there was so much oil on the transmission case and the crank case. We had secured some waste and rags in preparations for such an emergency and went to work on his carcass, but the more we wiped, the worse it got. Then Dad got the bright idea of washing him down with some coal oil and shortly we could see bare metal. When we finally got the crank case and transmission case visible a rather thorough inspection gave no hint of where the leak was. Being completely inexperienced in the ways of a motor car we never thought to start the motor while we had things exposed and watch for the oil to run out, so we put things back together with the mystery unsolved.

Next night when he drove into the yard, Dad's long face told me there was bad news coming with him. "Had to put a quart of oil in this critter today. It's running out some place." he said. "Well I guess that means another look after supper." I replied. "Say, do we have any tools if we have to take anything apart?" "I guess there are some under the back seat. We may have to get one or two new wrenches."

Dad was accustomed to making under or over statements, but that one was the understatement of his life. Before we were through bringing Oscar out of the coma induced by his long overdue breakdown we had enough new tools to stock a small machine shop. The only part of the deal that kept Dad from following Oscar in a dual breakdown was that the wrenches and parts were relatively cheap and buying them one at a time was not so painful. Later on Dad used to say "That darn car is two bitsing me into the poor house."

Anyway, after supper we found the cause of the oil leak. Somewhere along the merry way of his travels someone had replaced the conventional cast iron transmission case cover with one of cast aluminum and this, not having quite the resistance to vibration of the iron, had cracked during one of Oscar's occasional spells of hiccoughs. The crack was in the corner that tightened up on the arch gasket when the cover was replaced, so there was nothing for it but removal of the whole cover so the cracked corner could be welded.

To the mechanic that is a very simple job and before Oscar finally departed this troubled world, it was a small matter for us. But that first time the thought of its possibilities almost unnerved us.

By the time we knew for sure that the cover had to come off it was dark, so the extension cord had to be set up and by the time we figured out the wrenches we needed there was just time to make the first of uncounted trips eight blocks over the Ford agency.

Fortunately, although we did not have all the necessary tools for the job, we did get the important speed wrench and holding box wrench and so two hours, four barked knuckles and some hot language later we triumphantly lifted his bruised shell and carefully covered the raw exposed innards of his transmission with a piece of canvas.

The transmission cover with the three pedals bobbing back and forth was a rather ungainly thing and even though it had been washed with gasoline and water till it shone like one of mother's kitchen pans the passengers on the street car shied away from us as we clambered aboard.

"What are you going to do with that piece of junk, Frank?" queried Roy, who worked with Dad at the store. "That sir, is no piece of junk" Dad came back. "It is a perfectly good transmission case cover except for the broken corner which we are going to have welded."

"Oh Yes," said Roy, "Where is the corner?" At that Dad's jaw dropped a trifle and he grinned rather weakly. "Darned if I didn't leave it on the shelf in the garage."

"Won't get lost there, anyway." laughed Roy.

Dad took the cover to the welding shop and made arrangements to bring the broken piece in early next morning so it could be ready that night. With the cover repaired as good as new we went all through getting on the street car again, only this time the cover was not so clean and the car was more crowded. We had to get it home somehow, thought, and didn't know anyone with a car living out our way, so we just had to hang on to the thing and hope for the best. All the men who knew Dad, instead of sympathizing, had some smart crack to make about getting a horse or something equally as stupid and when we neared home old Jo Garside even had to say "Boys, I thought that critter was to ride in stead of carting around on the street car." I was pretty mad by then but Dad just laughed and allowed that we'd be riding again soon.

We felt a lot better after a good supper and when we went out to Oscar's domicile and saw him patiently waiting, with his floor boards neatly leaning against the wall we were all enthused to get him together right now. That wasn't as easy as it seemed thought. Since the carport or garage which housed him had a dirt floor it was necessary to spread papers around to set things on, and after carefully placing the newly repaired cover on the papers I proceeded to upset the case containing the nuts and bolts, washers and cotters. Unfortunately they didn't go on the paper so for the next few minutes I was picking pieces up and then washing the whole can full. Finally we were ready for the major operation of replacing the cover. since Oscar was of that vintage of automobile where the right front door opened but the left side of the driver's compartment was solid, that operation of balancing and setting the transmission cover in place with the foot pedal rods in the proper forks was for us a monumental task.

However, with our natural resourcefulness liberally mixed with ouches and small pieces of skin, we did it. Now all that remained, so we thought, was to insert the bolts and tighten them up. While we stood admiring our first achievement, Dad seemed to sag a little and I swear I could hear Oscar chuckle. "That does it," said Dad. "Let's take it off again and put the arch gasket where it belongs." Seems like we had forgotten to cement that little strip of felt over the magneto arch and it now reposed down in the transmission. Full of oil, of course, and no shellac would stick to it. Very carefully and tenderly we removed the cover again so as not to damage the other gaskets.

After what seemed endless attempts and dozens of stripped bolts we triumphantly replaced the floor boards on a completed job. Carefully wiping Oscar clean and doing the same for ourselves, I went around to his forward end and as Dad adjusted the gas and spark levers I applied pressure to the starting crank, and with an audible sigh of satisfaction at release from his enforced idleness, Oscar gave a few preliminary hiccough and then settled down to his usual soft purr.

Oscar's Breakdown

When the operation turned out successfully we all had high hopes that our troubles with Oscar were at an end, at least temporarily. They were, temporarily. For the balance of the week he transported us forth and back without a murmur and in the evenings we gaily motored to town, out the back roads and around where we had only dreamed of going. The world was rosy and we were on top.

Came Saturday night and the first cloud darkened our new-found paradise. Dad had a job at Pine Hills, some forty or fifty miles up in the hills back of town. That sounded fine at first reading but the joker was that the material for the job took up so much room there was only space enough for one passenger. Room for only one, and there were three of us waiting for such a chance. A trip to the mountain back country and only one to go. Susy and I were under voting age, so it didn't take long to decide who was going, and it wasn't us.

After the edge wore off the disappointment though, I got into the spirit of the occasion and helped Dad load the roll of heavy gauge linoleum, the buckets of paste and sand bags and tools. Oscar protested by various squeaks and groans the imposition of this unusual load and it took a little fast work in checking his oil, filling the side and tail lamps with coal oil, giving him a brisk rub-down and a check of the air in the tires to mollify him. He seemed satisfied at last as we added two spare casings to the load and made sure that the tire patch kit was in the box under the rear seat.

As they pulled out of the yard in the early dimness of that Sunday morning with Oscar weighted down by that immense load, I was certain that I detected a slight off-color note in the otherwise close harmony of the three voices, Dad, Mother and Oscar.

"Hold the place down children" came Dad's familiar expression as they turned into Daley St., "We'll be back around sundown."

Since the hour was much earlier than our usual Sunday morning rising schedule called for, I suggested a few hours more sleep as there was no one home to keep us up. Susy okayed the idea and thus a few of the long, slowly moving minutes of that day were disposed of.

When the harsh light of full daylight, aided by the rumbling of hungry young stomachs, finally forced us to abandon that method of killing time, we figured that we would make a project of breakfast.

There were a number of things in the cupboard that we knew were meant for the following week, but since there had been no specific prohibition on their use--well Mom won't care, too much, and anyway she got to go with Dad. Seemed good, sound logic to us.

The cost of living then, as now, always seemed to be one or two jumps ahead of the family income and we had a fair idea of the difficulties of maintaining a balanced budget. Mom never could quite arrive at that point of equilibrium anyway, so we figured a little more on the wrong side wouldn't make too much difference.

Normally if we had toast and jam with mush and milk we did not have bacon and eggs, or if we had the bacon and eggs, no flapjacks, so we decided to see what it was like to group them into one large, economy-size job.

"Susy, I have had more experience cooking," I told my sister, "so I'll cook and you can wash the dishes." "That's all right if you wipe them and put them away", she agreed, always ready to slip one over on me. in the ensuing argument breakfast was almost forgotten, but finally I got almost an even break and went to work on the food.

In the light of what happened to Dad, Mother and Oscar that day, it is a good thing they never saw that breakfast. As it was Mother never could quite figure out where those eggs, bacon and flapjack flour went, to say nothing of nearly a whole jar of jam. And for my part, in spite of cooking the meal I got hooked into doing most of the cleaning up.

Harvey Lee Bohanon