SEDE VACANTE 1362

September 12, 1362 —September 28 / October31, 1362

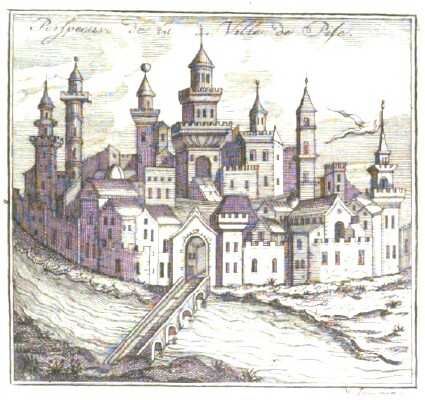

The Palace of the Popes, Avignon

Background

Because of the absence of the Papacy in France, conditions in Italy were gradually sliding into chaos. All of the changes taking place were to the detriment of the Patrimony of St. Peter and the influence and prestige of the Papacy. In France itself, the effects of the early part of the Hundred Years' War were devastating. The Battle of Crecy (1347), the capture of Calais (1347) and the Battle of Poitiers (1356) changed the political landscape of western Europe. Among other things, the Limousin—the native land of Pope Innocent VI and several of his cardinals—was now in the hands of the English. King John II of France and many of his nobles were also prisoners of the English. For the King this situation lasted until the Treaty of Bretigny in 1360, when he was replaced as prisoner of state by his son Louis d' Anjou.

The Black Death added to the unsettled conditions, destroying entire towns or the major part of them. Florence, for example, lost 3/5 of its population, according to Matteo Villani, the brother of Giovanni Villani. Petrarch, who was a Canon of the Cathedral at Parma, wrote to his brother (Fam. XVI. 2) that in Parma and Reggio around 40,000 persons were dead. His brother Gherardo, a monk in the Chartreuse at Monrieux near Toulon, was the only survivor of thirty five members of the community (Gasquet, 32-33; cf. Cochin, 77). The Carthusian Order lost 465 members altogether in 1348, another 165 in 1349, and 270 in 1350. Of the 140 Dominicans at Montpellier, seven survived (Gasquet, 40). Avignon, too, had been hard hit. Petrarch's muse, Laura, was dead at Avignon, on Good Friday.

An anonymous Canon of the Cathedral of Bruges in Flanders, who was in Avignon in 1348, wrote a letter home on Sunday, April 27 ("Breve chronicon clerici anonymi," in Smet, Recueil, 14-18; Gasquet, 44-49, at p. 47):

...And it is said that altogether in three months—that is from January 25th to the present day—62,000 bodies have been buried in Avignon. The Pope, however, about the middle of March last past, after mature deliberation, gave plenary absolution till Easter, as far as the keys of the Church extended, to all those who, having confessed and been contrite, should happen to die of the sickness. He ordered likewise devout processions, singing the Litanies, to be made on certain days each week, and to these, it is said, people sometimes come from the neighbouring districts to the number of 2,000; among them many of both sexes are barefooted, some are in sackcloth, some with ashes, walking with tears, and tearing their hair, and beating themselves with scourges even to the drawing of blood. The Pope was personally present at some of these processions, but they were then within the precincts of his palace.... Know, also, that the Pope has lately left Avignon, as is reported, and has gone to the castle called Stella, near Valence on the Rhone, two leagues off, to remain there until times change. The Curia, however, preferred to remain at Avignon, (but) vacations have been proclaimed till the Feast of St. Michael. All the auditors, advocates, and procurators have either left, intend to leave immediately, or are dead.... (tr. Gasquet)

As Boccacio and others noticed, it was a time for throwing off of all constraints, whether political, social or religious. The end, personal or collective, was in sight. One saw both pogroms against the Jews and the hyper-religiosity of the Flagellants. With populations, armies and resources depleted, and with political organizations under extreme stress, the ambitious and the greedy seized the opportunity to grab whatever they could. Others sank into despair.

The Plague and New Cardinals

In 1360 [1361], there was a visitation of the plague in the territory of Avignon. Between Easter (March 28) and the Feast of St. James (July 25) there died around six thousand persons, including approximately 100 bishops and eight or nine cardinals ("Secunda Vita Innocentis VI", Baluzius I, 341, 355). The "First Life of Innocent VI" (Baluzius I, 341), states: "anno sequenti (qui fuit LXI. [1361]) fuit mortalitas magna quasi universaliter, sed praecipue in regno Franciae, mortuaeque sunt personae quamplurimae de bossis, antraxibus, carbunculis, et similibus ulcerationibus et inflaturis; regnavit hujusmodi pestis permaxime in locis et regionibus montanorsis, quibus naturaliter consuevit esse purus aer; quae loca utplurimum non invaserat pestis alia quae regnavit anno quadragesimo octavo [1348]. In hac etiam dicuntur esse mortuae plures personae notabiles et magni status quam in alia, durationis ipsius tempore compensato. Non enim ultra sex vel septem menses duravit haec, alia vero per annum etc ultra."

Matteo Villani (Cronica Liber X. capitolo LXXI, pp. 366-367 Dragomanni) records as "morti per la moria":

Erano morti in pochi di nella corte di roma il Vicecancelliere di Preneste [Pierre des Près, d. May 16, 1361], il Cardinale Bianco [Guillaume Court, OCist., d. June 12, 1361], quello d' Ostia e di Velletri [Petrus Bertrandi, d. July 13, 1361], quello di Calamagna [Jean de Caraman, d. August 1, 1361], messer Andrea da Todi detto il cardinale di Firenze [Francesco degli Atti, d. August 25, 1361], il cardinale della Torre [Bernard de la Tour, d. August 7, 1361], e quello che fu generale dei frati minori [Guillaume Farinier, d. June 17, 1361], e un altro [Petrus de Foresta, d. June 7, 1361]. Il papa volendo riformare santa Chiesa di cardinali, nel tempo delle digiune del mese di settembre detto anno ne fece altri otto: il cancelliere di Francia, l' arcivescovo di Ravenna assente, che poi mori in cammino, ed era Caorsino, l' abate di Clugni Borgognone, il vescovo di Nemorsi Francesco, l' arcivescovo di Carcassone nipote del papa, messer Guglielmo suo referendario ch'era di Limosi, il figliuolo di messer Pietro da san Marcello, e l' arcivescovo d' Aques in Guascogna, tutti oltramontani, e niuno ne fece italiano, dimostrando che di visitare la cattedra di san Piero a Roma era strano al tutto del desiderio e appetito degli' Italiani.

To those dead, according to Villani, should probably be added Pierre de Cros (d. September 23, 1361) [cf. the obituary of the Sorbonne, which places the death on September 11: A. Molinier & A. Lognon, Obituaires de la province de Sens. Tome I (Diocese de Sens) (Paris 1902), 749], who died shortly after the creation of new Cardinals.

Death of Pope Innocent VI

The early lives agree that Innocent was suffering from both physical and mental deterioration in his last months. The "Second Life" (Baluzius, column 356) states, "Post haec Dominus Innocentius modicum decumbens, cum esset senio et infirmitatibus confectus, die XII mensis Septembris obiit, et XIV. sepelitur in Ecclesiae Beatae Mariae de Donis." The "First Life" (Baluzius I, 344), states: "Tandem vero post labores multos et anxietates innumeras, quas habuit tam in corpore quam in mente propter varias et plurimas infirmitates et turbationes quae suo tempore tam sibi quam toti mundo, ut praemittitur, continguerunt, in pace quievit, anno Domini MCCCLXII. die XII. Septembris , pontificatus sui anno decimo." Innocent VI died on September 12, 1362, in the tenth year of his rule. He was buried initially in the Cathedral of Avignon, on September 14, but his remains were subsequently transferred to the Carthusian house at Villeneuve les Avignon, which he had chosen as his last resting place. The Papal Throne was vacant for forty-five days.

As soon as the funeral was over, the Cardinals wrote to their colleague, Cardinal Aegidius Albornoz, Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina, who was serving as Papal Legate in Italy, informing him of the death of the Pope [Baronius-Raynaldi 7, 66; Baronius-Theiner 26, no. 4, p. 63-64]; they wrote to the people of Bologna on the same day, to hold firm against Bernabo Visconti and to obey the commands of the Legate. It appears as though the Cardinals expected Cardinal Albornoz to remain in his Legation. Matteo Villani states (XI. xxvi, p. 422 Dragomanni) that there were twenty-one cardinals in the Conclave ("I cardinali essendo chiuso in conclave in numero ventuno"), but this is not correct. It is true that there were a total of twenty-one cardinals. But Cardinal Albornoz did not make the journey to Avignon. The day after his coronation, Pope Urban V wrote a letter to Cardinal Albornoz (quoted in full below), in which he informed him of his election and his coronation, and encouraged him in his work in Italy as Legate. If Albornoz had been present at the Conclave and Coronation, no such letter would have been written. The letter begins like the usual encyclical letter, announcing to one and all (with minor adjustments for a particular recipient) the election and coronation of the new Pope, but the second paragraph makes it an entirely personal document. Nonetheless, both paragraphs require the assumption that Cardinal Albornoz was not present to participate in the events announced in the first paragraph.

The Electors

Pope Innocent VI (Roger) had named fifteen cardinals in three creations during his ten-year reign (1353: Baluze I, 321-322; 1356: Baluze I, 331, 359; 1361: Baluzius I, 341and 973). Five of them died during his reign. In the same period fourteen cardinals from the Conclave of 1352 had died. There were therefore twenty-one surviving Cardinals at the time of Innocent's death. (Eubel I, 20 n. 4; Baumgarten, "Miscellanea Cameralia II," 41-42). Eighteen of them were French. Ten of the twenty-one cardinals were papal relatives.

Innocent appointed only one Dominican, Nicolas Roselli (1357-1362) of Tarragona, who had died at Majorca on March 28, 1362 [His life: Manuel de Medrano, Historia de la Provincia de España de la Orden de Predicatores IV (Madrid 1731), 67-88]. He appointed one Benedictine, Elias de S. Eredio (1356-1367); and two Franciscans, Guilelmus Farinerii (1357-1361), and Fortanerius Vassalli (1361, a cardinal for one month). Of these four, only one survived to attend the Conclave of 1362.

Cardinals attending:

- Élie Talleyrand de Périgord, Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano (1348-1364). His sister, Agnes de Perigord, married Giovanni duca de Gravina, son of King Charles II of Naples, in 1321. Archdeacon of Richmond (1322-1328) [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 138]. Dean of York (1347-1364) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers 3, 255]. [Eubel I, p. 16 and n. 4; Baluzius I, 770] (died January 17, 1364).

- Guy de Boulogne, son of Robert VII, Comte d' Auvergne et de Boulogne, and Marie de Flandre, niece of Robert de Bethune, Comte de Nevers et Flandre [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 115-118; and especially 120-129]. Cardinal Guy's niece, Jeanne d' Auvergne, was married to King John of France on September 26, 1349 [Etienne Baluze, p. 114]. He was also a relative of Emperor Charles IV. He was also Uncle of Cardinal Robert of Geneva (1371-1378), Pope Clement VII, 1378-1394 [Etienne Baluze, p. 119-120]. A cardinal for some twenty years, he was Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1350-1373) [Eubel I, p. 19 n. 3; Baluze I, 823], previously Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1342-1350), with the title of S. Crisognus in commendam.

He had been Archbishop-elect of Lyons (1340-1342); at the time of his appointment by Benedict XII he was still in minoribus ordinibus, being only about twenty years of age [Gallia christiana 4, 164-166]. Archdeacon of Flandres in the Church of Therouanne (Morinensis). In 1342 he was provided benefices in the Dioceses of Cologne, Trier, and Mainz by Clement VI [H. Sauerland, Urkunden und Regesten zur Geschichte der Rheinland III (Bonn 1905), no. 71 (October 5, 1342)]. He was appointed Legate to the King of Hungary in 1349, with the mandate to reconcile King Ladislaus and Quenn Johanna of Naples. In 1350, he was mandated to participate in the Jubilee; he met Petrarch in Padua in February, 1350. His mother, Marie de Flandre, was present in Rome for the Jubilee [Baronius-Theiner 25, sub anno 1350, no. 2, p. 478; Baluze I, 888]. He was one of the Cardinals appointed to examine the disorders in Rome, including the attempted assassination of Cardinal Annibaldo di Ceccano, Legate for the Jubilee of 1350. In 1352, he was in Avignon, where he provided the blessing for the new Abbot of l'Isle-Barbe near Lyon, Jean Pilfort de Rabastencs, appointed by Clement VI [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 124; Gallia christiana 4, 230 (May 15, 1352)]. Baluze states that the appointment came from Innocent VI, which cannot be correct; Clement VI was still alive until December 6, 1352. Cardinal Guy was provided Dean of S. Martin de Tours on November 12, 1352, on the recommendation of King John II of France, and held the office until his death [Baluze, Histoire, 121; Gallia christiana 14, 182]. Innocent VI was elected pope on December 18, 1352, and crowned on December 30, 1352. Cardinal Guy, suggested to Clement VI (according to Baluze) an embassy which he would undertake at his own expense to bring peace between the Kings of England and France; Clement, however, died before the embassy could begin, and it was actually authorized by Innocent VI. Cardinal Guy was in Avignon and did participate in the Conclave of December 16-18, 1352, despite the statement of Salvador Miranda, on information provided him by Dr. Francis Burkle-Young. In 1353 Guy de Boulogne was actually Legate in France, and then in England, though his efforts to bring about a peace were doomed to failure. In 1359 he was sent to Spain to mediate the differences between the King of Aragon and King Pedro of Castile; he was in Spain for three years [Martène et Durand, Thesaurus novus anecdotorum II, Letters XXVII, 868 (January 26, 1361); CXXXVII, 964 (May 15, 1361); CLXVII (June 13, 1361)]. Later in 1361, on the death of Robert VII, Comte d' Auvergne, Cardinal Guy returned to France, and, with his brothers, settled the estate [Baluze, 126]. "Boloniensis" - Audouin Aubert, from the diocese of Limoges, Bishop of Ostia e Velletri (1361-1363), previously Cardinal Priest of SS. Johannis et Pauli (1353-1361). Notary Apostolic. Papal Chaplain. Provost of S. Pierre d' Aire (1342). Canon and Prebend of Saint-Gery de Cambrai (1344). Prebend of Limoges. Dean of S. Irieix de Limoges. Archdeacon of Brabant (1348). Canon and Prebend of Liège (1348-1349). Bishop of Paris (1349-1350) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 158-159]. Archdeacon of Lincoln [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers 3, 503, 565]. Archbishop of Auxerre (1350-1352). Bishop of Maguelonne (1353). Nephew of Pope Innocent VI [Cardella II, 190-191; Baluzius I, 925]. He died on May 10, 1363.

- Raymond de Canilhac, Canon Regular of Saint Augustine, Bishop of Palestrina (1361-1373), previously Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1350-1361). Both of his uncles, Pons and Guy, were abbots of Aniane (Diocese of Maguelonne, 30 km. from Montpellier). His mother was the sister of Cardinal Bertrand de Deaulx. His sister, Dauphine, married Guy III d' Auvergne. His niece, Guerine, married in 1345 Guillaume Roger, the brother of Pierre Roger (Clement VI) [Etienne Baluze, Histoire de la maison d' Auvergne (Paris 1708), p. 195]. Raymond was Canon Regular and Provost of Maguelonne. Archbishop of Toulouse (1345-1350). He died on June 20, 1373.

- Nicola Capocci, Bishop of Frascati. (died July 26, 1368) [Baluzius I, 259, 898]

- Hughes Roger, OSB, son of Guillaume I Roger and Guillaumette de Mestre. His uncle, Nicolas Rogier, was Archbishop of Rouen (1343-1347). Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Damaso. (died October 21, 1363). Brother of Pope Clement VI. "Cardinal de Tulles" [Baluzius I, 845]

- Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille, OSB, of Limoges, Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere. Canon of Salisbury, Prebend of Charminster and Bere [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 97 (November 16, 1371)]. Canon of Salisbury, Prebend of Charminster and Bere [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 97 (November 16, 1371)]. Archdeacon of Berks [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 168 (October 10, 1371)]. Archdeacon of Taunton in the Church of Wells [Bliss-Twombley IV, 187 (August 24, 1373); Le Neve, Fasti I, 167]. (died October 4, 1369) "Consanguineus et cubicularius ipsius Papae [Clementis VI]" [Baluzius I, 259, 902; Eubel I, 19.]

- Elias de S. Eredio (Élie de Saint-Yrieix), OSB, born in the diocese of Limoges, Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1356-1363). Doctor of law, Doctor of Theology. Bishop of Uzès (1344-1356) [Gallia christiana 6, 635-636]. Abbot of S. Florentii Salmuriensis (diocese of Angers) (1335-1344) [Gallia christiana 8, 638]. He died in Avignon on May 10. 1367. [Baluzius I, 931]

- Pierre de Monteruc, of Donzenac in the Limousin, Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1356-1385). Papal Chaplain. Provost of S. Pierre de Lille (1353). Canon, Prebend and Archdeacon of Elne (1354-1385). Treasurer of Bayeux (1355). Canon of Liege. Notary Apostolic. Prebend and Archdeacon of Hesaye (1355). Bishop of Pamplona (1355-1356). Prebend of Notre-Dame de Aix-La-Chapelle (1357) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 202-204]. (died May 20, 1385). Vice-Chancellor S.R.E.. Nephew of Innocent VI [Baluzius I, 934]

- Pierre Itier de Sandreux, of Perigord, Cardinal Priest of Ss. IV Coronati (1361-1364), subsequently Bishop of Albano (1364-1367). Doctor of laws. Previous to the cardinalate he had been Bishop of Sarlat (1341-1359 ?) [cf. Gallia christiana 2, 1515-1516], Bishop of Dax (1359-1362) [Gallia christiana 12, 320-321]. Treasurer of Wells (1362-1367). Precentor of Chichester [Bliss-Twombley, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 26 (January 29, 1368)]. In 1363, he was made Canon and Prebend of Liège and Archdeacon of Brabant [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 162]. He died on May 20, 1367. "Aquensis (Dax)"

- Joannes de Blandiaco (Jean de Blauzac), born at Blauzac near Uzés, he was the nephew of Cardinal Bertrand de Déaulx Bishop of Sabina (1348-1355). Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (1361-1372). Doctor in utroque iure. Bishop of Nîmes (1348-1361). (died 1379). "Nemausensis" [Cardella II, 204-206]

- Aegidius (Gilles) Aycelin de Montaigu, born in the Auvergne, Cardinal Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti (1361-1378), on the recommendation of King John of France. Chancellor of the King of France (1356-1361) at the time of his promotion to the cardinalate [Duchesne, Histoire des chancelliers , 344-346]. Bishop of Therouanne (1356-1361). Nephew of Clement VI [Baluzius I, 956], Doctor of Canon Law (Paris). (died December 5,1378)

- Androuin de la Roche, OSB.Clun., Burgundian, Cardinal Priest without titulus, then Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello, created at the request of the Kings of England and of France. Former Abbot of Cluny (1350-1361). Nuncio to England in 1360, he arranged the Treaty of Bretigny between King John II and King Edward III [Baluzius I, 364, 958; Cardella II, 202-204; Calendar, pp. 630-631; Rymer, Foedera 3, 160, 206, 230]. He was also commissioned to inform the King about the depredations of Bernabo Visconti of Milan in papal territories in Italy, and to enlist his help [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, 631 (July , 21, 1360)]. Legate in the Romandiola (1363-1368). He returned to Rome on April 13, 1369 [Eubel I, p. 20 n.2]. (died October 29, 1369) Androuin's brother was the Comte de la Roche.

- Guillaume de la Jugié, son of Jacques de la Jugié and Guillaumette Rogier, sister of Clement VI. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin. (died April 28, 1374). Archdeacon of Canterbury (1370-1374) [Bliss-Twombley, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 133 (June 24, 1374); Le Neve I, 41]. [Baluzius I, 854]

- Nicolas de Besse, of Limoges, son of Jacques de Besse, Seigneur de Bellefaye, and Almodie, sister of Clement VI. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1344-1369). Canon of Paris. Canon and Prebend of Liège (1351-1369). Archdeacon of Condroz in the Diocese of Liège (1344-1369). Rector of the parish of Neerlinter (1351-1369) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 179-180] (died November 5, 1369). Nephew of Clement VI [Baluzius I, 874]. "Lemovicensis"

- Pierre Roger de Beaufort (aged ca. 31), of Limoges, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova (1348-1370). Provided as Archdeacon of Canterbury (1343-1370) [Bliss, Calendar of Papal Registers III, p. 2 (June 25, 1343); p. 263 (November 20, 1347); Le Neve Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I, 40-41]. (died March 27, 1378). [Baluzius I, 259, 275] Nephew of Clement VI.

- Rinaldo Orsini, Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (1350-1374). Archdeacon of Campine in the Church of Liège (1323-1374) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 168-171]. Dean of Salisbury (June 14, 1347-June 6, 1374 [Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae II, 615]. (died June 6, 1374) [Baluzius I, 907]

- Stephanus Alberti (Étienne Aubert), Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro. (died September 29, 1369). Former Abbot of St. Victor in Marseille. Prebend of Wistow in the Church of York, attested 1369-1370 [Le Neve III, 226]. Grand-nephew of Pope Innocent VI, nephew of Cardinal Audouin Aubert [Baluzius I, 961; Cardella II, 206] "Carcassonensis"

- Guillaume Bragose, of the Diocese of Mande in the Limousin, Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1361-1362); after the Conclave he was promoted Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1362-1367). Major Penitentiary. "Vabrensis" [Baluzius I, 365, 961; Cardella II, 207]. He died on November 8,1367.

- Hugues de Saint-Martial, born in the diocese of Toul in Aquitaine, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (1361-1403). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica. Doctor in utroque iure [Cardella II, 207-208]. Provost of Kilmacduagh, Ireland. Canon and Prebend of Milton Ecclesia in the Church of Lincoln, attested in 1365, but resigned before 1372 [Le Neve Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae II, 187]. Archdeacon of Meath [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, 120 (April 1, 1372)]. Canon and Prebend of York [Bliss-Twemlow, p. 123 (March 20, 1373)]. (died 1403).

- Aegidius (Gil) Álvarez de Albornoz, Canon Regular of Saint Augustine, Bishop of Sabina. (died August 23, 1367) [Baluzius I, 259, 891]. A descendant of Alfonso V of Aragon. He was Papal Legate in Italy from 1353. On December 23, 1361, Pope Innocent refused him permission to return to Avignon from his Legateship [Martène et Durand, Thesaurus novus anecdotorum II, Letter CCXLVII, 1068-1069]. During the Sede Vacante, the College of Cardinals wrote to the Marchesi d' Este, habeatis efficacioribus favoribus studiisque ferventioribus commendatum, hostibus et persecutoribus ecclesiae predicte ac vestris resistendo viribus, ac venerabili fratri noswtro domino Egidio dei gratia Episcopo Sabinensi, apostolice sedis legato, et dilectis in Christo filiis populo Civitatis Bononiensis favorabiliter assistere [A. Theiner, Codex diplomaticus dominii temporalis Sanctae Sedis (Roma 1862) II, no. CCCLXVI, pp. 402-403 (September 14, 1362)] (See Pope Urban V's letter to him on November 13, 1362, below—Theiner no. CCLXVII, p. 403).

A special situation arose with the appearance in Avignon of Cardinal Andouin de la Roche. This Abbot of Cluny (1351-1361) had been appointed a Cardinal Priest in the Consistory of September 17, 1361, nearly a year before Pope Innocent's death. He did not, however, make his appearance in the Curia until the very day of the Pope's death, indeed (unless the sources exaggerate) at the very hour when the Pope was in extremis. Though he had never been in Consistory in the Pope's lifetime, had never had his mouth opened or closed, he now was given a voice in the Conclave ("Prima Vita Urbani VI", Baluzius I, 364-365; 980-981):

In hac autem electione fuit praesent et tanquam in ipsa vocem habens admissus et in conclavi cum aliis Cardinalibus introductus Dominus Androinus de Rocha prius Abbas Cluniacensis, qui per dictum Innocentium Papam VI. factus fuerat Presbyter Cardinalis, tamen cum nondum haberet titulum, nec vivente dicto Innocentio in consistorio fuerat installatus. Intravit enim primo curiam dum dictus Innocentius laborabat in extremis, immo et quasi hora qua moriebatur. Quod ideo hic notanter inserendum duxi ut appareat quod sola assumptio seu promotio ad cardinalatum dat vocem in electione Papae, et non titului assignatio. Et hoc expresse denotat regularis seu communis observantia, quae habet quod noviter promoto ad dictum statum per Papam clauditur os antequam sibi titulus assignetur; sicque manet ore clauso, et vocem in nullo habens, donec demum sibi aperiatur; et tunc sibi titulus assignatur. per quod ut inposterum loquatur, vocemque liberam habeat tam in dicta electione quam in aliis actibus ad statum hujusmodi pertinentibus, tribuitur eidem et conceditur facultas quae per dictam oris clausuram suspensa fuerat et effectualiter interdicta. Hoc etiam denotat verbum claudere, quod non potest locum habere nisi in re jam aperta. Et ita pro vero et indubitato et de jure tunc tentum, habitu, et determinatum extitit concorditer per Dominos Cardinales.

The Camerarius S. R. E. was Msgr. Arnaud Aubert, Archbishop of Auch (1357-1371), nephew of Innocent VI and brother of Cardinal Audouin Aubert, the Bishop of Ostia. He died on June 11, 1371. The letter granting him judicial powers as Camerlengo (December 6, 1361) is published in C. Samaran and G. Mollat, La fiscalité pontificale en France au XIVe siècle (Paris 1905), pp. 168, 221-224.

Conclave

The novendiales for Pope Innocent concluded on September 22, 1362. The Conclave opened in the evening of the same day, the Feast of Saint Maurice, in the Apostolic Palace in Avignon ("Vita Secunda Urbani V", Baluzius I, 399; Baronius-Raynaldi 7, sub anno 1362, viii, p. 69).

The six Limousin cardinals were prepared to use their collective influence to elect one of their number as pope. This might seem a reasonable hope, since thirteen of the twenty-one cardinals were of French origin. The Limousin, however, had recently fallen under the control of the King of England, which greatly diminished the attractiveness of a Limousin candidate. According to Jean de Froissart, Cardinal Élie Talleyrand de Périgord was happy to be under consideration as papabile, as was Cardinal Guy de Boulogne. According to the "First Life" (Baluzius I, column 363-364), there were many strong and well-prepared candidates, but the electors were unable to agree on one of their number:

Modus autem suae assumptionis seu electionis magis a Deo quam ab homine videtur processisse; attento praesertim quod dicta sede apostolica tunc vacante erant in collegio Cardinalium multi valentes et sufficientes viri, qui tamen, ut creditur, Deo sic disponente, concordare nequiverunt ut ipsorum aliquis eligeretur.

Matteo VIllani, however, tells a different story in his Cronica, that the Cardinals were able to come to an agreement. Their choice fell on an aged cardinal from the Limousin of the Benedictine Order—this would appear to be Hugues Roger, OSB—who received fifteen votes. The spiritually-minded Cardinal Hughes, however, made the 'Great Refusal', which was accepted by the Cardinals. Yet another monk making a refusal of the Throne of Peter! (Book XI, capitolo xxvi, p. 422 Dragomanni; Baronius-Raynaldi 7, 65, note by J. D. Mansi):

I cardinali essendo chiusi in conclave in numero ventuno a di 28 di settembre [sic!], si trovo che dato aveano quindici voci al cardinale ... che fu vescovo di ... monaco nero, e di nazione Limogino, uomo per eta antico e per vita di penitenza, e del tutto dato allo spirito, a cui essendo revelato lo squittino, avanti che pubblicato fosse papa con molto fervore d'amore e umilita rinunzio. I cardinali, perche per avventura non era chi arebbono voluto, accettarono la rifutagione.

Whether Villani believes that the Conclave began on September 28 or that the election took place on September 28 depends upon the punctuation of his sentence. After Cardinal Roger's refusal, according to Matteo Villani, votes were widely distributed among three candidates, including apparently the Cardinal of Toulouse (Étienne Aubert, nephew of Andouin Aubert ? or Raymond de Canillac?). The issue appears to have been whether to choose another Limousin, the grand-nephew of Pope Innocent, or not:

Appresso il cardinale di Tolosa nipote del cardinale d' Aubruno ebbe undici voci delle ventuno, un altro dieci, un altro nove, onde a'trenta di settembre gara entrò tra' cardinali, ed erano in grande discordia, ch'una parte d'essi il volea Limogino, e l'altra no. In fine ... il di ultimo d'ottobre elessono in papa messer Guglielmo Grimonardi...

Yet another story is told by the chronicler Jean de Froissart, who records the visit, in the Fall of 1362 of King John II—now free of his English detention— to his newly acquired dukedom of Burgundy (Premier Livre, § 500; Volume II, p. 78-79 ed. Luce):

Environ le Noel, trespassa de ce siècle li papes Innocens. Si furent li cardinal en grant discort de faire pape, car çascuns le voloit estre, et par especial li cardinaulz de Boulongne [Guy de Boulogne] et li cardinaulz de Pieregorch [Élie Talleyrand de Périgord], qui estoient li plus grant de tout le collège. De quoy, par leur dissension, et qu'il furent grant temps en conclave, li collèges se misent et arrestèrent dou tout en l' ordenance et disposition des deux cardinaulz dessus nommés. De quoi, quant il veirent que il avoient falli à le papalité et qu'il ne le pooient estre, il disent ensamble que nulz des aultres ossi ne le seroit. Si eslisirent l'abbé de Saint Victor de Marselle, qui estoit moult sains homs et de belle vie, grans clers et qui moult avoit travilliet pour l'eglise en Lombardie et ailleurs. Si le mandèrent li doi cardinal que il venist en Avignon. Il vint au plus tost qu'il peut: si reçut ce don en bon gré, et fu creés papes et appellés Urbains Ve.

The King was in fact in Avignon long before Christmas. On November 22, 1362, he participated in the solemn transfer of the remains of Pope Innocent VI from the Cathedral of Notre Dame des Domps to the Chartreuse of Villeneuve-les-Avignon, which the late Pope had founded (Prou, p. 8 and n. 7). Froissart's chronology is often defective. The King could well have been in the neighborhood of Avignon in September. On September 12, he was in the Chalonnais, and on October 19 at Chalons-sur-Saone [Prou, 2-3]. Apparently, however, Froissart's account of the Conclave does not leave room for the election of Hughes Roger, as Matteo Villani would have it. Froissart's account is consistent, though, with the narration of the "First Life".

Finally, whatever the details of the political in-fighting, the Cardinals came to give attention to Abbot Guillaume Grimoald, who at the time was serving as Legate in Naples. According to a report in the "Prima Vita Gregorii XI," (Baluze I, 376), it was Cardinal Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille (one of the cardinals of Limoges) who directed the attention of the Conclave toward Abbot Grimoald, in return for which favor, five years later on May 20, 1367, Pope Urban created Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille, "the Younger", OSB, of Limoges, a 27 year-old canon lawyer and Notary, nephew of the Cardinal of Santa Maria trans Tiberim, a Cardinal. This sounds excessively post hoc, ergo propter hoc. In any case, the Cardinals gave Grimoald their votes (perhaps on September 28), but did not publish the result of their scrutiny. Nor could they, because a response from the successful candidate was required, "Acceptasne electionem de te canonice factam?" They sent for Abbot Grimoard to come to them personally, uncertain as to whether they should achieve a consensus as to his election, and whether he would accept ["Prima Vita Urbani V", Baluzius I, 364]:

Non tamen ea publicaverunt donec et quousque ipse personaliter ad ipsos venit, haesitantes an electioni suae hujusmodi suum vellet praebere consensum, quem, licet cum tremore et timore, praestitit...

The same situation, the election of a non-cardinal who was not present at the Conclave, had pertained in 1264-1265; in 1271-1272; and in 1304.

Election

Villani says (Book XI, capitolo xxvi, p. 423 Dragomanni) that the election was kept secret until October 31, the day after he arrived in Avignon:

I cardinali perchè non era in Avignone, come scritto avemo, quando fu eletto, lo tenono celato, e mandarono per lui fingendo per certe cagioni averne prestamente bisogno, e segretamente a di 30 d'ottobre entrò in Avignone, e a di 31 fu pubblicato papa, e nomato Urbano quinto: prese il manto e la corona a di 6 di novembre.

On October 28, according to the "Prima Vita Urbani V" (Baluzius I, 363), Guillaume Grimoald was elected Pope, that is, he had arrived in Avignon and met with the Cardinals and made his formal acceptance of the offer of the papacy. The "Secunda Vita Urbani V" (Baluzius I, 399), however, says that he did not arrive until October 31, since his journey was delayed by flooding on the Rhone and Durance rivers: "tanta vero fuit inundatio Rhodani et Durantiae quod usque ad fossata pertingeret civitas, et dominus papa intrare non potuit usque in vigilia Omnium Sanctorum" (Prou, page 4 and n. 4, and page 5-6). The Introitus and Exitus, however, give the date of the election as October 31 [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers IV, vi], which would have been the date of the acceptance.

The New Pope

At the time of his election, Guillaume Grimoald was Legate of the Apostolic See in the Kingdom of Sicily. Matteo VIllani says that he was about sixty years of age.

His father Guillaume (who was still living) was a knight and the seigneur de Grisac, in the diocese of Mende (Prou, 3-4; Baluzius I, 974). His mother was Amphélise de Montferrand. The new pope's brother was Armand, Vicomte de Polignac. Guillaume had begun his career as a monk in the Priory of Chiriac (which had been founded from Saint Victor de Marseille), where his uncle was the Prior (Magnan, 86). It was there that he was ordained a priest. He was a student at Montpellier (where he studied literature), then Toulouse and finally Paris. He took his doctorate in Canon Law at Montpellier on October 31, 1342 [Guiraud III, i-v]. He was professor of Canon Law at Montpellier (as had been Cardinal Pierre Bertrandi in his earlier career), and he also taught in Avignon—a total of twenty years. He had been Vicar-General of Clermont and of Uzès, and then Abbot of St. Germain d' Auxerre from February 13, 1352 ( or 1357: Magnan, 88 n. 2). After the appointment he was immediately sent on an embassy to Milan, to Archbishop Giovanni Visconti (Archbishop since 1342, died October 5, 1354), who had become ruler of Milan after the mysterious death of his brother Luchino Visconti. Archbishop Visconti's ambition was to create a Lombard empire for himself, and he had invaded the Papal territory of Bologna, for which outrage he had been excommunicated by Clement VI (Lecacheaux, 410 f.). The excommunication did not prevent the Archbishop from occupying Bologna, however, and adding it to his growing empire. Grimoard was able to put together an agreement, signed on April 27, 1352, which made Visconti the Pope's vicar for Bologna (Lecacheaux, 416-417), thereby turning Archbishop Visconti from an enemy of Papal government into its agent. On August 18, Grimoard's legateship was prolonged for another three months, and on October 2, he was able to formally proclaim Archbishop Visconti as Vicar of Bologna in the name of the Pope. He was back in Avignon by December 20, 1352.

Pierre d' André, Bishop of Clermont (1349-1357), at some point chose Abbot William Grimoard to be his Vicar-General. In 1357, the new Bishop of Uzès, Pierre d' Aigrefeuille (1357-1366), also made Grimoard his Vicar-General (Magnan, 87). In April 1361, however, he was made Legate again by Pope Innocent VI and sent to Italy to deal with Barnabo Visconti (the Archbishop's nephew) and reinforce Cardinal Albornoz (Magnan, 116-118). One of his associates on this mission was John of Novavilla, Prior of the Carthusians at Avignon (Petrus Dorlandus, IV. 24). His mission, however, was not successful, and he was back in the Curia in June. It was Albornoz who was able to save Bologna from the Visconti. As a recompense for his services, the Pope named Grimoard Abbot of St. Victor en Marseille in 1362 (Magnan, 119-120; the date is uncertain). He had little time to settle in, however, since the Pope immediately sent him to Italy again, this time to Naples, to console Queen Joanna on the death of her husband, Louis of Taranto, who had died on May 26, 1362.

Coronation of Urban V

Pope Urban V was consecrated a bishop by Cardinal Andouin Aubert, the Dean of the Sacred College (Baluzius I, 976), and crowned on November 6, 1362. He was not crowned, as Ciaconius-Olduin state, by Cardinal Arnaud de Via, who had died in 1335.

Urban V himself speaks of his coronation of November 6, in his Electoral Manifesto, Nuper videlicet, written to Cardinal Albornoz, Legate in Italy (Baronius-Raynaldi 7, sub anno 1362, viii, p. 69; Baronius-Theiner 26, p. 66):

Urbanus, etc. Venerabili fratri Aegidio [Albornoz] episcopo Sabinensi A(postolicam) s(alutem) D(icit):

Nuper, videlicet 11. Idibus septembris proxime elapsi, piae recordationis Innocentio Papa VI. praedecessore nostro viam universae carnis ingresso, ejusque corpore cum solemnibus exequiis in ecclesia Avenionensi deposito, ad locum alium, quem ipse (dum ageret in humanis) elegerat, postmodum transferendo, venerabiles fratres nostri S. R. E. Cardinales, tempore debito secundum praecepta canonum missarum solemniis in honorem Spiritus sancti in electionem summi Pontificis, quae facienda imminebat, eisdem per suam affuturi gratiam, devotissime celebrandis, convenerunt insimul in palatio apostolico Avinionense, in quo idem praedecessor tempore sui obitus vivitabat, de substitutione ejusdem Pontificis tractaturi, aliquibusque tractatibus in hoc praebabitis, prout tanti negotii qualitas requirebat, tandem iidem fratres ad nos, qui tunc in minori constituti officio certae nuntiationis ministerium a praefato praedecessore nobis injunctum gerebamus in partibus Italiae, intuitum dirigentes, nos in Summum Pontificem et pastorem universalis ecclesiae concorditer elegerunt. Nos autem, qui sumus cinis et pulvis, ex hoc fuimus non immerito stupefacti, cum oculi nostri imperfectum nostrum evidenter cernerent, et nec vires corporis, nec virtutum merita, nec scientiae donum nobis suppeterent ad apostolici culminis speculam conscendendam, et gravissiman totius orbis sarcinam nostris debilibus humeris perferendam. Cogitantes tamen quod ecclesiae praedictae diuturna vacatio, praesertim diebus istis, quibus (peccatis exigentibus) totus fere orbis in maligno est positus, magna posset pericula generare; ac confidentes in Deo, qui nos, licet indignos, ad pascendum oves universi sui gregis elegit, quod sua consueta misericordia ad ipsius laudem et gloriam, ac nostram et totius populi Christiani salutem in ejusdem populi salubri regimine dabit fortitudinem debili, indigno virtutem et scientiam ignoranti; cum timore ac tremore divinae voluntati paruimus, ac eorumdem fratrum desideriis annuentes, fragilitatis nostrae colla jugo submisimus apostolicae servitutis, et hesterna die octavo idus novembris consecrationis et benedictionis munus et coronationis insignia recepimus, ut est moris.

Ad praemissa itaque nobis necessaria obtinenda facilius tuarum orationum suffragiis tuae praegrandis prudentiae solicitudine prosequaris in terris tuae legationis, charitative comportans studio impositam nobis universalis oneris gravitatem, ut mediantibus tuis auxiliis de grege nobis a supremo episcopo et pastore commisso bonam eidem rationem reddere valeamus.Caeterum pragravem tuorum laborum farcinam, solicitudinis indefessae solertiam, et variaorum cogitationum aufractus aetatis tuae gravedine cumulatos, quibus pro felici statu et honore sanctae Romanae ecclesiae, cujus honorabile membrum existis, adeo vexaris assidue, quod dulcedinem quietis ignoras, per experientiam, qua illos tecum quandoque communicaveimus in minori officio constituti, certa scientia cognoscentes, tibi de illis paterne compatimur, et majoris adstringimur vinculis charitatis; gerentes in votis ac proposito illa (Domino adjuvante) peragere, quae tuis consolatione ac desideriis reddantur accepta, honorem ejusdem fraternitatis adaugeant, ac nostris et ecclesiae praedictae subjectis, quos provide regis et protegis, expectatae quietis tribuat incrementum.

Datum Avin(ione) VI. id novembris anno 1 [November 13, 1362].

Had Cardinal Albornoz been at the Conclave, all of the information contained in the letter would have been known to him, and there would have been no point to the letter.

The Papal Chamberlain was Archbishop Arnaud Aubert of Auch (1357-1371) [L. Grandmaison, Cartulaire de l' Archevêché de Tours I (Tours 1892), p. 27 no. xviii (June 26, 1364); Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 121: in cujus rei, etc., praesentes litteras fieri fecimus et sigilli nostri camerariatus appensi munivi]. There was no Cardinal Chamberlain.

It was Urban V who ordered the Campanile of the Vatican Basilica to be repaired and fitted with three bells (April 10, 1363); two years later he demanded a report on the repairs on the Campanile and on the building of the Vatican Palace from Peter Bohier Bishop of Orvieto (1364-1378), his Vicar in spiritualibus in Rome [Cennius and Martinetti, Collectio Bullarum Sacrosanctae Basilicae Vaticanae III, no. 1, no. 6]. This belltower played an important role in the uncanonical election of "Urban VI" in April, 1378.