SEDE VACANTE 1303

October 11, 1303 —Octoberr 22, 1303

Pope Boniface VIII proclaiming the Jubilee of 1300

Giotto, fresco in S. Giovanni Laterano

New Cardinals

During his pontificate, Boniface had created fifteen cardinals, none of them French [Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica I second edition, pp. 12-13; Cardella II, 49-70]. This was a deliberate policy, to redress the imbalance created by Celestine V under the influence of the Angevin Charles II of Naples. It was also a response to the breach between Pope Boniface and King Philip IV of France. Seven of the new cardinals were relatives of various popes. Three new Franciscan cardinals balanced the number of Benedictines created by Celestine. For the year 1296, around Pentecost, there is a list of cardinals, twenty-three in number, in the records of the Chamber of the College of Cardinals [J. Kirsch, Die Finanzverwaltung des Kardinalkollegiums (Munster 1895), p. 115].

- Benedetto Caetani, named Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano. (died December 14, 1296). Nephew of Pope Boniface VIII.

- Jacopo (Giacomo) Tomassi Caetani, OFM, former bishop of Alatri, named Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente. (died January 1, 1300).Nephew of Pope Boniface VIII.

- Francesco Napoleone Orsini, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in Orthea (Silice). (died after May 24, 1312). Nephew of Pope Nicholas III

- Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi, Auditor of the Sacred Roman Rota, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro. (died June 23, 1341). Grand-nephew of Nicholas III. [Cardella II, p. 51]

- Francesco Caetani, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin). (died May 16, 1317). Nephew of Pope Boniface VIII.

- Pietro Valeriano Duraguerra, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica (died December 17, 1302).

- Gonzalo Gudiel, Archbishop of Toledo, named Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano. (died December 1299).

- Teodorico Ranieri, Archbishop-elect of Pisa, Chamberlain of His Holiness, named Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme. (died December 7, 1306).

- Niccolò Boccasini, OP, Master General of the Dominicans, named Cardinal Priest of S. Sabina. (died July 7, 1304). Trevisanus.

- Riccardo Petroni, Sienese, Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. (died February 10, 1314).

- Leonardo Patrasso, Archbishop of Capua, named Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano. (died December 7, 1311). Uncle of Pope Boniface VIII.

- Gentile Partino, OFM, Doctor of Theology and Lector of Theology in the Roman Curia, named Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti. (died October 27, 1312).

- Luca Fieschi, of the Counts of Lavagna, of Genoa, named Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata. (died January 31, 1336). A blood relative of King Jaime II of Aragon. Nephew of Adrian V (Fieschi).

- Pedro Rodríguez, bishop of Burgos, Spain, named Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina. (died December 20, 1310).

- Giovanni Minio da Morrovalle (or da Muro), OFM, Minister General of the Franciscans, named Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto. (died August 1312).

He and the French King were, in fact, locked in what was both a struggle of wills and a power struggle, each trying to reduce the other to compliance. In September 1302 the Pope had excommunicated the King [Baronius-Raynaldus, sub anno 1302, xvi; p. 329; done on the Feast of the Dedication of St. Peter's Basilica]. But on November 24 Pope Boniface sent Cardinal Jean de Cressi "Le Moine", OSB, Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro, to France as his legate, giving him the power to lift the excommunication [Baronius-Raynaldus sub anno 1302, xv; p. 330]. This overture to composing their differences was rejected by King Philip.

Political Background: Anagni

King Philip had decided to carry the dispute to the Pope's front door. He sent his Chancellor, Guillaume de Nogaret, to Italy, to raise opposition to Boniface within the Papal States. Assisting Guillaume were Jean Monschet, a French gentleman, and two 'hommes de robe', Thierry d' Hiricon and Jacques de Gefferin [Baillet, 168]. They made the castle of Staggia near Siena, which belonged to Mussiato de Francesis of Florence, their headquarters. Giovanni Villani's chronicle (Book VIII, chapter 65) provides the dramatic outlines of the events of Boniface's last weeks:

After the said strife had arisen between Pope Boniface and King Philip of France, each one sought ot abase the other by every method and guise that was possible: the Pope sought to oppress the king of France with excommunications and by other means to deprive him of his kingdom; and with this he favored the Flemings, [Philip's] rebellious subjects, and entered into negotiations with King Albert of Germany, encouraging him to come to Rome for the Imperial Benediction and to cause the Kingdom to be taken from King Charles, his kinsman, and to stir up war against the king of France on the borders of his realm on the side of Germany.

The king of France, on the other hand, was not asleep, but with great caution, and by the counsel of Stefano della Colonna and of other sage Italians, and men of his own realm, sent one William of Nogaret of Provence, a wise and crafty cleric, with Musciatto Franzesi, into Tuscany, furnished with much ready money, and with drafts on the company of the Peruzzi (which were then his merchants) for as much money as might be needed; the Peruzzi not knowing wherefore. And when they were come to the fortress of Staggia, which belonged to the said Musciatto, they abode there a long time, sending ambassadors and messages and letters; and they caused people to come to them in secret, giving out openly that they were there to treat concerning peace between the Pope and the king of France, and that for this cause they had brought the money; and under this color they conducted secret negotiations to take Pope Boniface prisoner in Anagni.

And as it had been purposed, so it came to pass. For Pope Boniface being with his cardinals and with all the Court in the city of Anagni in Campania, where he had been born and was at home, not thinking or knowing of this plot, not being on his guard, or if he heard anything of it, through his great courage not heeding it, or perhaps, as it pleased God, by reason of his great sins—in the month of September, 1303, Sciarra della Colonna, with his mounted followers, to the number of 300, and many of his friends on foot, paid by money of the French king, with troops of the lords of Ceccano and of Supino, and of other barons of the Campagna, and of the sons of Maffio of Anagni, and, it is said, with the consent of some of the cardinals which were in the plot, one morning early entered into Anagni, with the ensigns and standards of the king of France.... they rode through the city without any hindrance ... and when they came to the Papal Palace, they entered without opposition and took the palace, since the assault was not expected by the Pope and his retainers, and they were not on their guard. Pope Boniface—hearing the uproar, and seeing himself forsaken by all his cardinals who had fled and were in hiding, whether through fear or through malice, and by the most part of his servants, and seeing that his enemies had taken the city and the palace where he was—gave homself up for lost.... but he caused himself to be robed in the mantle of Saint Peter, and with the crown of Constantine on his head, and with the keys and the cross in his hand, he seated himself upon the papal throne.

And when Sciarra and the others, his enemies, came to him, they mocked at him with vile words and arrested him and his household which had remained with him. Among others, William of Nogaret, who had conducted the negotiations for the king of France, scorned him and threatened him, saying that he would take him bound to Lyons on the Rhone, and there in a general council would cause him to be deposed and condemned.... no man dared to touch [Boniface], nor were they pleased to lay hands on him, but they left him robed under light arrest and were minded to rob the treasure of the Pope and the Church. In this pain, shame and torment, the great Pope Boniface abode prisoner among his enemies for three days,,,. the People of Anagni beholding their error and issuing from their blind ingratitude, suddenly rose in arms... and drove out Sciarra della Colonna and his followers, with loss to them of prisoners and slain, and freed the Pope and his household. Pope Boniface... departed immediately from Anagni with his court and came to Rome and St. Peter's to hold a council... but... the grief which had hardened in the heart of Pope Boniface, by reason of the injury which he had received, produced in him, once he had come to Rome, a strange malady so that he gnawed at himself as if he were mad, and in this state he passed from this life on the twelfth day of October in the year of Christ 1303, and in the Church of St. Peter near the entrance of the doors, in a rich chapel which was built in his lifetime, he was honorably buried. [see at the end for the discovery of his tomb and body]

Bernard Guidonis says that the attack on the Pope took place on the Vigil of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, September 7, and he adds that the pope was deserted by all of the cardinals except Niccolò Boccasini and Pedro Rodriguez, and betrayed by some of his own household (Baronius-Raynaldus, sub anno 1303, xli, p. 357; Muratori, RIS, p. 672):

Eodem anno millesimo trecentesimo tertio in Vigilia Nativitatis B. Maria Virginis, dum Bonifacius Papa Anagnia in patrio solo et civitate propriae originis tum suae curiae resideret, ubi tutus esse amplius merito crederetur in gente sua, et populo et natione, ibidem consciis aliquibus domesticis suis proditus fuit, captusque, atque tentus; et thesaurus suus et ecclesiae depraedatur et asportatur, non sine ignominia ecclesiae et dedecore grandi. Cardinales vero timentes, relicto eo, fugerunt, duobus exceptis, scilicet Domino Petro Hyspani Sabinensi et Domino Nicolao Ostiense Episcopis. Hujus captionis et sceleris vexillifer fuit Guillelmus de Nogareto de Sancto Felice Diocesis Tholosanae, complicibus et consentaneis Columpnensibus ex quibus duos olim decapellaverit Cardinales. Super ipsum itaque Bonifacium, qui reges et pontifices ac religiosos clerumque ac populum horrendo tremere fecerat et pavere repente, tomor et tremor ac dolor una die pariter irruerunt, aurumque nimis ssitens perdidit et thesaurum, ut ejus exemplo discant superiores praelati non superbe dominari in clero et populo, sed forma facti gregis ex animo curam gerere subditorum, priusque avari appetant quam timeri.

Many of these details are confirmed by an anonymous account of the main part of the attack. The presence of Cardinal Niccolò Boccasini is confirmed by his own Bull as Pope Benedict XI, Flagitiosum scelus (Perugia, June 13, 1304: Tosti, pp. 544-545), haec palam, haec publice, haec notorie et in nostris etiam oculis patrata fuerunt. Saint Antonino, son of Niccolo Pierozzi, Bishop of Florence (1389-1459), in his universal chronicle, continues the story of Boniface's confrontation with Philip's Chancellor, Guillaume Nogaret, a man whose grandfather had been burned by the Inquisition as a Patarene heretic (Raynaldus, sub anno 1303, xli; p. 357):

Animadvertent civitatem captam et palatium suum, judicavit [Bonifatius] se mortuum esse; sed ut magnanimus et inperterritus ait:"Ex quo proditore sicut Jesus Christus captus sum et deditus sum in manibus inimicorum ut occidar, ut Papa mori decerno." Et fecit se parari vestibus sacris cum pallio seu ammictu B. Petri et corona aurea a Constantino Silvestro Papae collata, et cum clavibus et cruce in manibus resedit in papali throno. Ad quem accedens dictus Sciarra cum aliis suis inimicis verbis contumeliosis aggressi sunt Pontificem et deriserunt circumstantes eum et familiares ejus et qui cum ipso remanserunt. Inter alios eum illusit Guillelmus de Lungbarreto, qui pro Rege Franciae tractatum duxerat captura Pontificis, et minatus est ei, quod ligatum upsum doceret Lugdunum ut in generali concilia solemniter deponeretur. Cui Papa, non corde deficiens, respondit: "Patienter feram me condemnari et damnari et deponi per Patarenos cujusmodi ipse erat cum progenitoribus suis ut Patarenis igne conbustis." Quibus verbis confusus Dominus Guillelmus cum rubore reticuit. Domino autem disponente ob dignitatem Apostolicae Sedis nemo ex inimicis ejus ausus fuit mitter in eum manus, sed indutum sacris vestibus dimiserunt sub honesta custodia et ipsi insistebant praeda, diripientes thesaurum ejus et ecclesiae quem in palatio Papae invenerunt.

Permansit Pontifex ipse custoditus tribus diebus. Tertia autem die surrexit a custodia liber sine precibus alicuius aut procuratione, Domino illustrante et velamen suae caecae ingratitudinis a populo Anagniae auferente. Recognoscentes ergo errorem suum cives Anagniae cum popula arma corriupuerunt in favorem Antistitis, clamantes per urbem, "Vivat Papa et moriantur proditores!" Et discurrentes per civitatem Anagniam ejecerunt Sciarram de Columna suosque complices de ea, pluribus ex eis captis et aliis occisis. Liberatus igitur Pontifex Bonifacius cum familia sua, dolore nimis absortus ex tanto dedecore cum tota Curia inde discedent, Roman remeavit ad S. Petrum, disponens concilium convocare ob injuriam sibi et eccleisae factam vindicandum contra Regem Franciae.

After a three day captivity at the hands of Guillaume Nogaret and Sciarra Colonna, Boniface was liberated by the citizens of Anagni and returned to Rome first to the Lateran Palace (according to Jacopo Caetani Stefaneschi: Raynaldus, xlii, p. 358) and then to the Vatican, intent on summoning a council to deal with the outrage. It is said by the Continuator of the Ecclesiastical History of Ptolemy of Lucca that Cardinal Matteo Rosso Orsini protected the Pope during his return to Rome (quoted in Cipolla, p. 155 n. 2):

populus Anagninus conversus est ad ipsum, cum aliquibus cardinalibus, et sic liberatus est Bonifacius de manibus eorum, et deductus Romam, sub protectione quorumdam cardinalium et praecipue d. Matthaei Rubei de Ursinis et in palatio Sancti Petri locatus, licet primo venerit ad Sanctum Iohannem de Laterano.

This confirms what Ferreto reports, quod Ursinorum primi Matheus et Iacobus prescientes ne hostis Urbem intraret neve Bonifacius de ipsis male conciperet, magna virorum copia fulti obviam exierunt, et apostolicum adventantem inter se capientes, illum ad sedem iuxta templum Apostolorum magno impetu perduxere. One of the cardinals who had betrayed the pope was Napoleone Orsini (Ferreto, p. 153 Cipolla; Tosti, 384), another Riccardo Petroni of Siena (Tosti, 387). News of what had happened at Anagni brought King Charles from Naples, along with his two sons, Robert Duke of Apulia and Philip Prince of Taranto, as well as military forces.

Pope Boniface died in the Vatican Palace on October 11, 1303, thirty-five days after the assault against him at Anagni. Jacopo Caetani Stefaneschi, an eyewitness, wrote of his return and his last days:

Protinus hunc solvit rediens festinus in almam

Urbem, quippe sacram, miro circumdatus orbe,

Vallatusque armis. O mira potentia tantis

Enodata malis! Numquam sic glorius armis,

Sic festus susceptus ea, cleroque decorus,

Insignisve fuit, cunctos ubi ferrea texunt.

Prima patrem sedes Lateranensis suscipit: inde

Aetherei Petri, cujus miracula seclo

Clara patent. Siquidem proprium defendere servum,

Tutarique patrem curae est devotius illi

Obnixum, tumulumque suum procumbere templo

Claviger imperitas. Paucl nam tempore fluxo,

Decursoque die, lecto prostratus anhelus

Procubuit, fassusque fidem, veramque professus

Romana ecclesia, Christo tunc redditur almus

Spiritus, et saevi jam nescit judiciis iram.

Sed mitem placidamque patris, ceu credere fas est.

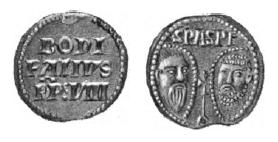

Lead bulla of Boniface VIII

The Electors

During the reign of Boniface VIII, twelve cardinals had died: from the group which had elected him were Hugues de Billon, Matthew of Acquasparta, Gerardo Bianchi, Simon de Beaulieu, Berardus de Got, Pietro Peregrosso, Tommaso de Aquila, Pietro de L' Aquila, Guillaume Ferrières, Nicolas de Nonancourt, Simon de Caritate, and Giovanni Castrocoeli. With his own death nine cardinals from the conclave of 1294 were still alive. Boniface himself had created fifteen cardinals, of whom four had died. Benedetto Caetani, Giacomo Tommasi-Caetani, Pietro Duraguerra, and Gonzalo Gudiel. A list of the cardinals who were alive at the time of the death of Boniface VIII has been assembled by Conrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica I second edition, p. 13 n. 10. See also: Cardella II, pp. 49-70. Ferreto of Vicenza gives a complete list of the cardinals (p. 170-171 ed. Cipolla).

Of Boniface VIII's fifteen cardinals, one was a Dominican, Nicolas Bocasini (1298-1303), who became Pope Benedict XI; and three were Franciscans, Jacopo (Giacomo) Tomassi Caetani (1295-1300), Gentile Gentile Partino de Montefiori (1300-1312), and Giovanni Minio da Morrovalle (or da Muro) (1302-1312). By contrast, six out of thirteen of Celestine V's cardinals were Regulars.

Cardinals in the Sacred College:

- Giovanni Boccamati (Boccamazza) [Romanus], a relative of Pope Honorius IV. Suburbicarian Bishop of Tusculum (Frascati). Chaplain of Pope Nicholas III. Archbishop of Monreale and Administrator of Monreale (1278-1286) [R. Pirro, Sicilia sacra I (Panormi 1733), 463], by appointment of Nicholas III [Registres de Nicolas III, no. 120, pp. 38-39]. He continued to administer that Church until the appointment of a successor [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 491-492, p. 347]. The successor, on July 22, 1286, was Peter of Reate [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 560, p. 388]. It was Cardinal Boccamazza who delivered the news of the Sicilian Vespers to King Charles I [V. D'Avino, Cenni storici sulle chiese arcivescovili, vescovili e prelatizie (nullius) del Regno delle Due Sicilie (Napoli 1848), 359]. On May 22, 1286, he was named by Honorius IV Sedis Apostolicae Legatus to Hungary, Bohemia, Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Prussia, Pomerania, etc. [Registres d' Honorius IV, no. 772-805; pp. 551-558; and cf. no. 585 and 771; Potthast 22466. Cardella II, p. 27], with powers to absolve former supporters of Conrad and Conradin [Potthast 22498 ((June 14, 1286); Eubel, Hierarchia catholica I, p. 11 n.2]. He entered Milan on August 30. He was certainly back at the Curia in Rome on April 22, 1288, two months after the election of Nicholas IV [Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 582, p. 116]. He subscribed on September 3, 1288 at Reate [Langlois, Registres de Nicolas IV, I, no. 243, p. 40]. His brother Angelo was Bishop of Catania in Sicily (1296-1303). He died in 1309 in Avignon.

- Niccolò Boccasini, OP [Prato; his actual birthplace is variously given], son of Boccasio a notary and his wife Barnaba; he had a sister, Adeletta [Fietta, 12]. At the age of ten his widowed mother placed him with the Dominican fathers in Venice; in 1254 he took the habit. Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia e Velletri. In April, 1301 he was instructed to consecrate Bishop Fernando of Segovia [Digard, Registres de Boniface VIII, no. 4043]. Between May 13, 1301, and May 10, 1303, Cardinal Niccolò was Apostolicae Sedis Legatus in Hungary, Poland, Dalmatia, Croatia, Rama, Serbia, Lodomeria, Galatia and Comania [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1302, no. 20, p. 308; Digard, Les registres de Boniface VIII, no. 4338]. He was one of the two cardinals who had remained with Boniface VIII when he was attacked by the French and the Colonna in September, 1303 [Baronius-Raynaldus, sub anno 1303, xli, p. 357; Muratori, RIS, p. 672]. He died. as Pope Benedict XI, on July 7, 1304. The cardinals each received a gift from the new Pope [Kirsch, Finanzverwaltung, p. 128].

- Teodorico Ranieri [Urbevetanus], Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (Civitas Papalis) [Registres de Boniface VIII, no. 3196, 3417]. Former Chamberlain of His Holiness. In 1299 he had been Capitaneus Patrimonii [Annales Urbevetani, in Ephemerides Urbevetanae (ed. Luigi Fumi) (Citta di Castello 1903) RIS XV.v, p. 172]

- Leonardo Patrassi, Suburbicarian Bishop of Albano

- Pedro Rodriguez, Suburbicarian Bishop of Sabina. He was granted the titulus of SS. Giovanni e Paolo in commendam by Boniface VIII on December 17, 1302 [Digard, Les registres de Boniface VIII, no. 5089].

- Giovanni Minio, OFM, Suburbicarian Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina.

- ? Jean de Cressi "Le Moine", OSB [of Cressi, in the Diocese of Amiens, in Picardy], Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro. Chamberlain of the College of Cardinals from November 6, 1305 to 1311. He had studied Canon Law, and was Doctor utriusque iure. Canon of Amiens, of Bayeux, and of Paris. He had been Dean of the Cathedral of Bayeux [Registre de Benoit XI, no. 81, p. 80]. Auditor of the Rota. Vice-Chancellor S.R.E. He was the executor of the Last Will and Testament of Cardinal Jean de Cholet, who had died of fever on August 2, 1292. He was sent as Legate to France after the Roman synod of October 31, 1302 [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1302, no. 16, p. 305], in the wake of the publication, on November 18, 1302, of Unam Sanctam [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1302, no. 13-14, pp. 303-304; Potthast 25189]; Cardinal Jean was given the faculties necessary to absolve King Philip IV if he submitted to papal authority. He was also given a list of twelve articles to present to the King [Roy, pp. 34-37]. The King rejected the approach, and forbade the publication of the pope's bulls and letters [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1302, no. 33, p. 325]. On March 4, he wrote to Cardinal Jean about liturgical matters in France, giving him permission to do as he thought best [Potthast 25218]. On April 13, 1303, Boniface wrote to Charles of Alençon that he had just received a letter from Cardinal Jean, which contained King Philip's responses to Boniface's demands: "responsiones eaedem certae et examinatae veritati contradicunt; nec rationi congruunt, nec consonant aequitati, nec sunt tales neque reperimus in eis illa, de quibus debeamus merito contentari..." [Baronius-Theiner 23, sub anno 1302, no. 16, p. 305; Potthast 25229]. On April 13, Boniface complained in a letter to the Cardinal that he was being given contradictory information about King Philip's position by the Bishop of Auxerre, Pierre de Mornay; by Charles of Alençon; and by the Count of Chartres [Potthast 25228; and cf. 25230]. [Roy, Histoire nouvelle des cardinaux françois V (Paris 1788), no. 1; Kirsch, p. 44]. On June 24, Philip held a colloquy in which France appealed to a General Council the proposition that Boniface VIII was an heretic. On August 15, Boniface suspended and interdicted the Bishop of Nicosia, who was inspiring Philip's moves, and excommunicated any and all subjects of France who tried to reach the Curia. The personal interdict was imposed upon the King [bull of Boniface VIII, Super Petri solio, September 8, 1303, in Bullarium Romanum Turin edition 4, xxii, pp. 170-174]. It seems unlikely that he would have left France without instructions from Boniface, and Boniface was dead and his successor elected (October 11—October 22) before the news could have reached Cardinal Jean in France and Jean could have reached Rome for the Conclave. (died August 22, 1313).

- Robert de Pontigny, OCist, Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana. (died October 9, 1305). Protector of the Cistercians, promotor assiduus [Dupuy, "Preuves," p. 85 (December 18, 1302)]

- Gentile Partino, OFM, Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti. He and Cardinal Niccolò Boccasini, OP, had been appointed by Boniface VIII to settle disputes between the Franciscans and Dominicans over distances between their establishments; their report was sanctioned by Benedict XI on December 5, 1303 [Registres de Benoît XI, no. 1165, pp. 707-711]. He frequently acted as Assessor in various minor cases, usually along with other cardinals. In February, 1304, he was a member of a committee that chose the new Bishop of Fossombrone [Registres de Benoît XI, no.518]. (died October 27, 1312).

- Matteo Rosso Orsini, a Roman, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (died September 4, 1305). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica [Potthast, no. 24945 (April 27, 1300); 24989 (November 3, 1300); 25001-25002 (January 3, 1301); no. 25028 (March 16, 1301)].

- Napoleone Orsini, son of Rinaldo Orsini, a Roman, Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano (died 1342). Nephew of Pope Nicholas III. [Cardella II, 33-37]. He was an examiner of bishops in the case of the Elect of Toulouse [Registres de Boniface VIII, p. 46, no. 2451 (17 March 1298)]. He was Apostolic Legate and Rector of the Duchy of Spoleto in February, 1301 [Digard, Registres de Boniface VIII, no. 3958]. Rector of the county of Sabina, July 6, 1301 [Digard, Registres de Boniface VIII, no. 4377].

- Landolfo Brancaccio, Neapolitanus, Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria. He was Legate to the Kingdom of Naples and King Charles II. [Registres de Boniface VIII, nos. 3402-3404]. On 11 February 1298 he was granted the power to name a Bishop for the diocese of Cassana [Digard, Registres de Boniface VIII, no. 2882]. (died October 29, 1312).

- Guglielmo Longhi [Pongo], of Adraria (Bergamo), Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano. He was granted the Basilica XII Apostolorum in commendam by Boniface VIII on March 3, 1302 [Registres de Boniface VIII, no 5010]. He held degrees in Theology as well as in Canon and Civil Law. He did not, as Olduin points out, share in editing the Sextum; that was Guillaume de Mandegot, Archbishop of Embredun (1295-1311). In 1298 he was appointed Auditor by Boniface VIII in the case of the reform of the Monstery of S. Gennaro in Vercelli [Registres de Boniface VIII, nos. 2761 (May 30, 1298)]. He was a Cardinal for twenty-five years. (died April 9, 1319, according to his monument in the Franciscan church of S. Nicolas in Bergamo: Olduin, Athenaeum Romanum, 205).

- Francesco Napoleone Orsini [Romanus], Nephew of Pope Nicholas III. Cardinal Deacon of S. Lucia in Orthea (Silice). Archpriest of S. Maria Maggiore (Basilica Liberiana) December 17, 1295. [Registres de Boniface VIII, no 2525 (March 21, 1298)].He was appointed with four other cardinals to perform the coronation of Emperor Henry VII, but he died before May 6, 1312. The Emperor Henry VII states in his letter to the King of Cyprus on his coronation day that Cardinal Francesco Orsini was deceased [MGH, p. 803]; and the surviving Cardinals remark in their Testimonium to the coronation [MGH, p. 797]: "nos praefati domini, nostri summi pontificis volentes oboedire mandatis, ad Urbem accessimus, bene memorie Albanensi episcopo et Domino Francisco prefatis viam universe carnis ingressis, invenimus ecclesiam Beati Petri apostoli taliter occupatam..." This statement could be taken to imply that Orsini was dead before they reached the city of Rome on May 6.

- Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi [Romanus, Trastevere], grand-nephew of Nicholas III. His father was Pietro di Stefano Stefaneschi, Senator of Rome. His mother Perna, daughter of Gentile Orsini, was sister of Cardinal Matteo Rosso Orsini. Giacomo was created Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1295-1341) by Boniface VIII. He had been made Canon of S. Peter's and Auditor of the Rota by Celestine V. He died on June 23, 1341 at Avignon. [The family tree is given by G. Navone in Archivio della società romana di storia patria 1 (1877) 239, and see p. 234].

- Francesco Caetani [Anagni], Son of Goffredo of Anagni, brother of Pope Boniface VIII. Canon of the Cathedral of Porto. Papal Chaplain. Treasurer General S.R.E. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1295-1317). Treasurer of York (1303-1306) [Rymer, Foedera III, 578; Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae III, 159]. He died on May 16, 1317 in Avignon.

- Riccardo Petroni [Senensis], Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio. Doctor utriusque iuri. He was granted the Deaconry of S. Maria Nova in commendam by Boniface VIII on December 17, 1302 [Digard, Les registres de Boniface VIII, no. 5089-5090]. He and Guglielmo Longhi were responsible for the editing of the Sextus Decretalium. His Last Will and Testament is reproduced in Benedetto Trombi, Storia critico-chronologica diplomatica del Patriarca S. Brunone e del suo Ordine Cartusiano VI (Napoli 1777), Appendix I, no. xlv., pp. lii-lvi. (died February 10, 1314).

- Luca Fieschi [Genoa], of the family of the Counts of Lavania, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1300-1305), with SS. Cosma e Damiano and S. Marcello in commendam [Eubel I, p. 13 n. 7]. Later he was Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (1306-1336) (died January 31, 1336)

There were two cardinals who did not attend, because they had been excommunicated and deposed by Pope Boniface:

- Jacopo (Giacomo) Colonna, a Roman, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata, with S. Marcello in commendam. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica. (died August 14, 1318 in Avignon.)

- Pietro Colonna, a Roman, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (died 1326). Nephew of Cardinal Giacopo Colonna {Cardella II, 37-38] His brother was the notorious Sciarra Colonna.

Conclave and Election of Cardinal Boccasini

The Conclave of 1303 took place in the Vatican Palace, as the regulations of Gregory X specified, not, as some 19th century authors relate, at Perugia [Funke, 9]. The Mass of the Holy Spirit was sung on October 21 [Piatti, VII, 393]. From the beginning the attention of the electors was fixed on Cardinal Niccolò Boccasini, the former Master General of the Dominicans, one of the two cardinals who had remained with Boniface VIII at Anagni. Boccasini had been ambassador to King Philip IV in 1297, in an attempt to bring about peace between France and the England [Funke, 10-11; Ferretton, 29-32]. In the words of Ferreto, "benignus et mitis iurgia oderat et pacem amabat;" he was kind and gentle, hated strife and loved peace.

Benedict XI speaks of the Conclave which elected him in his election manifesto, Opera divinae potentiae (issued from the Lateran on November 1: Raynaldus, sub anno 1303, xlvii; p. 360):

Nuper enim felicis recordationis Bonifacio Papa VIII. praedecessore nostro, sicut Domino placuit, de hac luce subtracto, et sicut speramus post labores impensos ad praemium evocato, ejusque corpore cum exequiarum solemnitate debita tradito ecclesiasticae sepulturae, nos tunc ut praetangitur Episcopus Ostiensis, caeterique fratres nostri episcopi, presbyteri et diaconi Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae Cardinales ad tractandum de Romani substitutione Pontificis in palatio S. Petri de Urbe in quo decesserat pridem ipse, convenimus. Nobisque ac ipsis ad id eligentibus per viam procedere scrutinii, contingit illo faciente, qui concordiam diligit, quod unico facto a publicato scrutinio, tanta finaliter in votis eorumdem fratrum est inventa concordia quod per eos de nobis licet immeritis fuit ad apostolatus officium xi Kal. Novembris proximo futuri electio celebrata.

The day before Benedict signed his Manifesto, October 31, 1303, he had written to the Archbishop of Milan and his suffragans in the same terms, Dominus ac Redemptor noster [Grandjean, Registre de Benôit XI, no. 1, pp. 1-4].

The date of Cardinal Boccasini's election was October 22, 1303. On his own testimony he was elected on the first ballot.

Coronation of Benedict XI

Coronation of Benedict XI, with Charles II at right

Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Cardinal Niccolò Boccasini was crowned as Pope Benedict XI in the Vatican Basilica on Sunday, October 27, 1303, by Cardinal Matteo Rosso Orsini, the Cardinal Protodeacon. In attendance were King Charles II of Naples and his sons (Ferreto, 169-170 ed. Cipolla, though Ferreto's dates of the death of Boniface and election of Benedict are wrong, and he states that the coronation took place in the Lateran Basilica). He reigned for eight months and seventeen days (Raynaldus, sub anno 1304, xxxi; p. 387), or nine months and six days (Panvinio), dying at Perugia on July 7, 1304 [Grandjean, Mélanges d' archéologie et d' histoire 14 (1894), 241-244].

During his brief reign, Benedict created three cardinals—all Dominicans. Two were named on December 18, 1303: Nicholas Alberti, OP, the Bishop of Spoleto; and William Macclesfield, OP, the Prior of his Order in England. William died at the end of 1303 or at the beginning of 1304, and he was replaced by Walter Winterburn, OP (who died on September 4, 1305). It was already being said in Rome on January 16, 1304 that William Macclesfield was dead [Finke, Acta Aragonensia no. 109 p. 160]. King James II of Aragon had asked the new Pope for a cardinal or two [Finke, Acta Aragonensia no. 106 p. 156 (Valencia, January 1, 1304)]—and he recommended Raymond Despont of Valencia (1291-1312), Arnoldus de Jardino of Dertosa (1273-1306), Bernardus Peregrini, OP, Prior of the Dominicans in Aragon; and A. Olibe, OMin., Minister of the Franciscans—but he received nothing.

The election of Benedict XI did not go unchallenged. A manuscript from the National Archives in Paris [Finke, Acta Aragonensia I (Berlin 1908), no. 104, pp. 153-154] rehearses a long list of defects in the orthodoxy of Boniface VIII and in the circumstances surrounding the Conclave of 1303. While the author is unknown, it is not unlikely that it derives from the same circle that was seeking to exculpate the Colonna and the French by blackening the reputation of Boniface VIII. Among other things, it is alleged that Boniface had had contacts with an heretic (Arnold of Villanova), who had been condemned by the University of Paris and by Boniface himself. This alone made him an heretic. The election of Benedict XI was uncanonical, it was alleged, because it began by violating the Constitution of Gregory X, Ubi majus , which required ten days to elapse between the death of the late pope and the beginning of the Conclave; Boniface died on October 11, and Benedict was elected on October 22. It was also alleged that the participants had been followers of Boniface the Heretic, and were therefore excommunicated. Real cardinals were not summoned and awaited, as required by Ubi majus, and when they wanted to come, they were not admitted (This would refer to the Colonna cardinals, who had been excommunicated and degraded). The Cardinals had permitted Charles of Sicily and his soldiers to be present in the City, but had refused a similar request from the King of France. It was alleged that the Elect had been ordained by a heretic, and was therefore ineligible.

Discovery of the Tomb of Boniface VIII.

In 1605, during the demolition of some altars of the Old St. Peter's basilica, the tomb of Boniface was discovered. The details are provided by the Ceremonial Diaries of Giovanni Paolo Mucanzio [Gattico I, 478-479]:

Anno 1605. die XI. mensis Octobris dum demolirentur altaria antiquae ecclesiae S. Petri post altare S. Bonifacii Papae IV. in loco eminenti et sub imagine B. Mariae opere musivo depictae in polo marmoreo, inventum est corpus Bonifacii VIII., qui obiit anno dom. 1303. Erat autem ejus corpus fere integrum, et in alia capsa lignea inclusum, quae cum corpore portata fuit in Sacristia Canonicorum et ibi conservata per duos menses, et corpus dicti Pontificis fuit a multis visum. Ego etiam ad illud curiositatis causa videndum semel atque iterum accessi; et vidi dictum corpus integrum conservatum in dicta capsa lignea, in qua fuerat sepultum, post trecentos et duos annos. Facies tamen ejus aliquantulum consumpta erat, ita ut nec narices nec labia, sed tantum mentum et dentes apparerent. Habebat in capite mitram albam admodum parvam, ut conjectare potui, ex tela bombacina, et corpus indutum erat inbibus pontificalibus indumentis, idest caligis, et sandaliis ex tela aurea in summitate acutis, et sine cruce, rocchetto longo, alba, stola, cingulo, dalmatica, tunicella, planeta laba sericea coloris nigri, fanone, et pallio, quod consumptum erat, sed plumbum apparebat et pendebat fere usque ad pedes. Spinulae tres etiam aderant gemmatae. Manus ejus chyrothecis albis sericeis acu factis, et margaritis ornatis indutae erant. anulum pretiosum in digito gestabat nempe zaphyrum, ut quidam dicunt, valoris 300. scutorum.

The body was found nearly intact in a wooden coffin. It was carried to the Sacristy, where it was on view for nearly two months. This is vouched for by Giovanni Paolo Mucanzio, the papal Master of Ceremonies, who saw the body several times. The face was somewhat decayed, so that it had lost both nose and lips, though the jaw and teeth were intact. He had been wearing a short white mitre on his head, and the body was dressed in full pontificals, with stockings and sandals, though many of the vestments were decayed. His hands wore white silk jeweled gloves, and he had a jeweled ring on his finger.

Bibliography

Charles Grandjean (editor), Les Registres de Benoit XI. Recueil des bulles de ce pape Premier fascicule (Paris; E. Thorin 1883).

Giovanni Villani, Ioannis Villani Florentini Historia Universalis (ed. Giovanni Battista Recanati) (Milan 1728) [Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Tomus Decimustertius].

Carlo Cipolla (editor), Le opere di Ferreto de' Ferreti Vicentino I (Roma: Forzani 1908). Max Laue, Ferreto von Vicenza. Seine Dichtungen und sein Geschichtswerk (Halle: Max Niemeyer 1884). [ca. 1295/1297-ca. 1337]

Henry Richards Luard (editor), Flores Historiarum Vol. III. A.D. 1265 to A. D. 1326 (London: HM Stationery Office/Eyre & Spottswoodie 1890).

Georges Digard, "Un nouveau récit de l' attentat d' Anagni," Revue des questions historiques 43 (Paris 1888), 557-561.

J. J. J. von Döllinger, "Ex Chronicis Urbevetanis ab eo qui hoc tempore vixit scriptis (Cod. lat. Monac. 149, fol. 150 sqq.," Beiträge zur politischen, kirchlichen, und Cultur-geschichte III. Band (Wien 1882), 347-353.

Odoricus Raynaldus [Rainaldi], Annales Ecclesiastici ab anno MCXCVIII. ubi desint Cardinalis Baronius, auctore Odorico Raynaldi. Accedunt in hac Editione notae chronologicae, criticae, historicae... auctore Joanne Dominico Mansi Lucensi Tomus Quartus [Volume XXIII] (Lucca: Leonardo Venturini 1749), sub anno 1294 (p. 26).

Bernard Guidone, "Vita Bonifacii VIII," in Ludovicus Antonius Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores Tomus Tertius (Milan 1723), 670-672. Bernard Guidonis [Gui], OP, of Royères in the Limousin, Bishop of Lodève (ca. 1261—1331): U. Chevalier, Repertoire I, 1919-1920. Cardinal Giacomo Caetani Stefaneschi, "Vita Coelestini Papae V Opus Metricum," in Muratori, 613-641. Ignaz Hösl, Kardinal Jacobus Gaietani Stefaneschi. Ein Beitrag zur Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte des beginnenden vierzehnten Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Emil Ebering 1908). Ivano Sartor, Papa Benedetto XI (Nicolo Boccasino) beato di Treviso (Editrice S. Liberale: 2005).

Iacobus Schwalm (Editor), Monumenta Germaniae Historia. Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum Tomus IV. inde ab a. MCCXCVIII usque ad a. MCCCXIII. Pars II (Hannoverae et Lipsiae: Hahn 1909-1911) nos. 777-812. [MGH]

Bartolomeo Platina, Historia B. Platinae de vitis pontificum Romanorum ...cui etiam nunc accessit supplementum... per Onuphrium [Panvinium]... et deinde per Antonium Cicarellam (Cologne: Cholini 1626). Bartolomeo Platina, Storia delle vite de' pontefice edizione novissima Tomo Terzo (Venezia: Ferrarin 1763). Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa Tomo secondo (Roma: Pagliarini 1792). Giuseppe Piatti, Storia critico-cronologica de' Romani Pontefici E de' Generali e Provinciali Concilj Tomo settimo (Poli: Giovanni Gravier 1767). 385-395 Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Annali d' Italia Volume 19 (Firenze 1827).

Ioannes Rubeus, Bonifacius VIII e familia Caietanorum Principium Romanus Pontifex (Romae: Corbelletti 1651). Adrien Baillet, Histoire des demeslez du pape Boniface VIII avec Philippe le Bel Roy de France 2nd ed. (Paris: Florentin Delaulne 1718). Antonio Scoti, Memorie del Beato Benedetto XI. (Treviso: Eusebio Bergami 1737). Constantin Höfler, Rückblick auf P. Bonifacius VIII. und die Literatur seiner Geschichte (1842). J.-B. Christophe, L' histoire de la papauté pendant le XIV. siècle Tome premier (Paris: L. Maison 1853) 78-175. Lorenzo Fietta, Niccolò Boccasini e il suo tempo (Padova 1874). Martin Souchon, Die Papstwahlen von Bonifaz VIII bis Urban VI (Braunschweig: Benno Goeritz 1888), pp. 15-23. Félix Rocquain, La papauté au Moyen Age (Paris 1881), 211-291. Louis [Luigi] Tosti, [OSB,] History of Pope Boniface VIII and his times (tr. E. J. Donnelly) (New York 1911; original edition in Italian 1846). Charles Grandjean, "Benoît XI avant son Pontificat, 1240-1303," Mélanges d' archéologie et d' histoire 8 (1888), 219-291. Charles Grandjean, "La date de la mort de Benoît XI," Mélanges d' archéologie et d' histoire 14 (1894), 241-244. Arsenio Frugoni, Il giubileo di Bonifacio VIII ed. A. De Vincentiis (Rome- Bari: Laterza, 1999). Ferdinando Ferretton, Beato Benedetto XI Trivigiano (Treviso:Enrico Martinelli 1904). F. Gregorovius, History of Rome in the Middle Ages, Volume V.2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell, 1906), Book X, chapter 5, pp. 515-525. H. Denifle, "Die Denkschriften der Colonna gegen Bonifaz VIII. und der Cardinale gegen die Colonna," Archiv fur Literatur- und Kirchen- geschichte V (Freiburg im Breisgau 1889), 493-529. Paul Funke, Papst Benedikt XI. (Munster 1891). Vito Sibilio, Benedetto XI: Il papa tra Roma e Avignone (2004).

Giulio Navone "Di un mosaico di Pietro Cavallini in S. Maria in Trastevere e degli Stefaneschi di Trastevere," Archivio della società romana di storia patria 1 (1877) 219-239. Ignatz Hösl, Kardinal Jacobus Gaietani Stefaneschi (Berlin 1908) [Historische Studien LXI]. Arsenio Frugoni, "La figura e l'opera del cardinale Jacopo Stefaneschi," Rendiconti dell' Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 3a s., 5 (1950), 397-424.

Hermann Ströbele, Nicolaus von Prato, Kardinalbischof von Ostia und Velletri. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Kardinalates zu Beginn des 14. Jahrhunderts (Freiburg i. B. 1914). V. Fineschi, Supplemento alla vita del Cardinale Niccolò da Prato, religioso domenicano (Lucca: Vincenzo Giuntini, 1758).

John Marrone and Charles Zuckerman, "Cardinal Simon of Beaulieu and relations between Philip the Fair and Boniface VIII", Traditio 21 (1975), 195–222