Every year, 5,000 new immigrants serve in the military with the promise that they will be granted U.S citizenship. However, that promise is broken when government policies allow for the deportation of these veterans against their will after they have served the country, a devastatingly common scenario the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) calls “discharged, then discarded.”

To bring visibility and awareness to deported veterans, the Veterans Resource Center and DREAM Center of the University Student Union (USU) hosted Deported Veterans on April 12. Four panelists shared their experience with deportation and their interactions with deported U.S. veterans.

“The VRC understands the importance of veteran deportation and is dedicated to lending a supportive hand to the community,” said Mayra Plascencia, manager of the Veterans Resource Center. “This diverse panel shines a light on the complex challenges deported veterans experience and motivates the CSUN community to extend their advocacy toward the deported veterans community.”

Panelist Andres Kwon speaks at Deported Veterans.

According to panelist Andres Kwon who is a policy counselor and senior organizer with the ACLU of Southern California, immigrants have been serving in the military since the American Revolution. By the 1840s, half of the military was made up of immigrants. Currently, as stated by fwd.us, the military has about 700,000 foreign-born veterans with 45,000 being active members. As of 2018, 17% of those foreign-born veterans have not been naturalized. An unknown number of veterans have been deported to 50 countries.

Kwon specializes in the intersection of immigrants’ rights, policing, and criminal justice reform. When discussing the criminalization of immigrants and how veterans are deported, he said that many immigrants enlist because they are promised naturalization, especially during times of war as stated in the Immunization and Naturalization Act of 1952. However, according to Kwon, the U.S government still may not grant naturalization.

“Even when veterans have or when people who are serving did apply, they still fell through the cracks because the U.S. government just misplaced their paperwork or for a while, you were deployed abroad and so they missed out...There have been a lot of obstacles with the U.S government actually following through,” Kwon said.

Being a deported veteran also has a significant impact on mental health. Laura Meza, a veteran who served in the Maryland and Washington D.C. area with hopes of becoming a dentist after active duty, was deported to Costa Rica in 2009. As a deported veteran and a victim of rape while serving in the military, she said she deals with depression and has had suicidal thoughts in the wake of this trauma. She said she currently is in therapy and treatment, and that her biggest loss is not being able to see her family who live in the U.S. She speaks to her children through video calls.

“I really miss my family and it’s been really hard not to be there. Not to be a mother to my daughter. Not to be with my family, my sisters and my mom and dad,” Meza said.

Deported veteran Laura Meza shares her story.

The media often politicizes immigration rights and excludes intersectionality, resulting in deported veterans being overlooked, observed Nancy Landa, a CSUN alumna and former president of Associated Students, who was deported to Mexico 11 years ago and still resides there. In her advocacy work, she has noticed how immigration rights often are U.S.-centric and neglect the complexity and diversity of global stories. Landa wonders if there will ever be a time when immigration justice will be served.

“In the end, if I’m not victimized or I don’t talk about my story in a traumatic or victimized way, it is not deserving of attention or inclusion in the advocacy agenda,” said Landa. “It feels like it’s always this frustration; when are we really gonna have this overarching conversation about immigration justice and does it have an expiration date?”

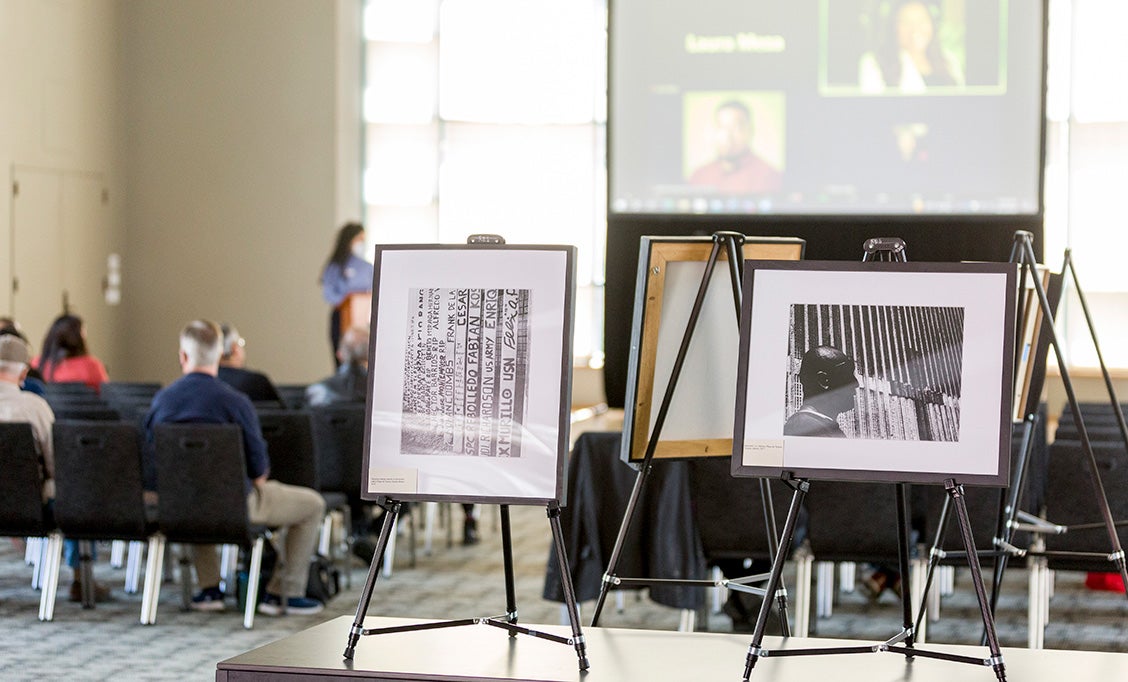

An exhibit of veteran Joseph Silva’s photography was displayed for attendees during the panel discussion. Each photograph focused on deported veterans doing various activities such as enjoying ice cream together in Tijuana, Mexico. Another photograph showcased dog tags from Tijuana’s Deported Veterans Support House. Silva started his work in 2015 when he saw a social media post about U.S. military veterans being deported. He said he appreciated getting to know deported veterans he got to work with on a personal level.

“What’s memorable is spending time with the guys and the women that are deported,” said Silva. “Spending time with their families. I always have my camera with me but I’m not always taking photographs. Sometimes I’m just in the moment with them.”

Veteran Joseph Silva’s photography on display.

For more information and all other upcoming events for the Veterans Resource Center, please visit www.csun.edu/vrc.