The Great Gallery Beyond: CSUN Art Alumnae in the Public Sphere

written by Teresa Morrison

Beatriz Cortez has long made work inspired by planetary forces, migration, and the malleable nature of time. In Glacial Erratic, her sculpture installation that was on view at New York City’s Rockefeller Center this fall, she struck all those chords. Made of steel frame and sheet metal, the epic sculpture evokes stone masses that settled in earthen grooves and crevices formed during the last Ice Age by melting ice. Hidden in plain sight, these glacial erratics blend with the landscape but differ from native rocks in content, appearance, size, and shape. Cortez’s sculptural equivalent is no subtle mass. Mammoth and glinting, set amid the art deco glamour of Rockefeller’s city within a city, the work is meant to stop visitors in their tracks to consider potential meanings.

Cortez earned her M.A. in studio art at CSUN and went on to earn an MFA at California Institute of the Arts, all while teaching full-time as a professor of contemporary Central American literature in CSUN’s Department of Central American and Transborder Studies. She is the most recent in a prestigious line of alumnae to distinguish CSUN in the public art realm, including Judy Baca, Michele Martínez, and Betty Beaumont.

Glacial Erratic embraces community through monumental gesture. Cortez taught herself to weld while studying art at CSUN, an essential skill if she was to actualize her futuristic nods to ancient earth machinations and human practice. Commissioned by the inaugural Frieze Arto LIFEWTR Sculpture Prize, which selected Cortez’s proposal from 120 applications representing artists across 30 countries, Glacial Erratic was intentionally designed to age with exposure to elements and foot traffic, highlighting vulnerability amid strength on a planet where geologic time is corrupted by intensive human activity. Speaking with Inga Nelli in Coeur et Art magazine, Cortez said she hoped that in encountering the work passersby would read the material, ponder the form, and “imagine migration and movement in planetary ways, through processes that have taken millions of years and that continue into the future.”

Installation was fraught. Frieze Sculpture at Rockefeller Center was meant to coincide with Frieze New York in the spring, but the citywide fair was cancelled for 2020 when New York City emerged as the first Covid-19 hotspot in the United States. Some exhibits shifted to virtual viewing rooms, but Frieze Sculpture went forward, offering an artful respite to a city under siege and in desperate need of hope. The circumstances complicated Cortez’s plans, but she called on her community of friends, family, and colleagues to make the installation happen. They worked from their homes in quarantine pods and with diligent social distance and personal protective equipment at the studio. As Cortez watched her communities come together to help realize Glacial Erratic at such an uncertain time in U.S. politics and history, she was reminded of the essential goodness that finds us in hard times. “It was so beautiful,” she told a virtual audience at the inaugural speaker series of the California State University system’s new ConSortiUm art collective. “So difficult not to start to cry, thinking what an amazing gift we have with our community, what an amazing gift to employ the labor of our community to tell our stories together.”

Born in El Salvador, Cortez’s work examines difficult topics—memory and loss in the aftermath of war, the experience of migration, global climate crisis. For her contribution to In Plain Sight, a multimedia art performance event that straddled the U.S. Independence Day weekend in 2020, Cortez had the phrase “NO CAGES NO JAULAS” skytyped in monumental letters by a fleet of planes directly above the Los Angeles Immigration Court on Olive Street. In Aquí Estamos (We Are Here), a 2019 installation at John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, she highlighted existential crisis with a humble cairn of boulders that had been buried under ice for millions of years but exposed in our lifetime by global warming. Importantly, Cortez refuses to embrace nihilism in tackling these weighted issues. That she surrounds the Ice Age boulders with a garden of corn, beans, and potatoes—sustenance for people on a threatened planet—highlights the humanity that is ever present in her work, generous measures of optimism and confidence in the potential for divergent entities to coexist.

Futurism imbues much of Cortez’s work in material content and form, referencing space travel, timeless wisdom, and speculative fiction to realize transcendent possibilities for communities often ignored by mainstream art worlds. She has constructed space capsules with indigenous influences and steel renderings of artisanal and ancient architecture, paying tribute to the migrant labor that’s typically invisible in historical records. When Tzolk’in, an otherworldly steel sculpture based on an ancient Mayan agricultural calendar, was commissioned for the Made in L.A biennial in 2018, she discussed her intent with curators that in addition to the installation at the Hammer Museum, a companion piece commissioned by Clockshop was to be placed at the side of the Los Angeles River. Hammer curators agreed, and the two sculptures were installed 20 miles apart, one in the rarefied space of the museum—where it was protected but also invisible to Angelenos who don’t frequent museums and galleries—and one on the humble concrete bank of a city aqueduct. Cortez highlighted the concept of entities bound by common characteristics but separated in space and circumstance. At the same time, she challenged notions of art placement and conservation by taking art objects of equivalent importance and value, placing one in pristine gallery space and exposing the other to potentially destructive elements and interactions.

While Cortez often welcomes an artwork’s evolution through interaction, other artists see preservation and restoration as inevitable necessities when installing work in public environments. Judy Baca, one of Los Angeles’s most celebrated artists, formed the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) 45 years ago with a mission not only to create “sites of public memory” for historically disenfranchised communities, but to preserve those sites for future generations.

Baca, who earned both her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Art at CSUN, is perhaps best known for the Great Wall of Los Angeles, which employed over 400 youths and family members from disparate social and economic backgrounds to complete an epic mural depicting the often silenced and distorted history of ethnic peoples in California. The mural, completed over five summers, occupies one half mile of the San Fernando Valley’s Tujunga Wash flood control channel, a tributary of the same L.A. River where Cortez’s Tzolk’in was sited. The placement is not coincidental. The river cuts through L.A. neighborhoods in all their varied demography and geography, a physical and metaphorical link that binds Los Angeles’s diverse populations. Such placement makes the art accessible but exposes it to damage—elemental and intentional—requiring phases of restoration over intervening decades. SPARC manages all expenses and labor and routinely applies for grant funding to maintain Baca’s work.

While the Great Wall is Baca’s best-known work, her most widely viewed is more likely Hitting the Wall. The mural, commissioned by the 1984 Olympic Summer Games in Los Angeles and painted on an I-110 underpass near the 4th Street exit, celebrates the debut that year of women in Olympic marathon competition. For the better part of four decades the mural was a staple of freeway commutes through the downtown Los Angeles corridor. A lean runner—muscular, powerful, and unmistakably female—extends her arms like wings as she appears to burst through the freeway wall, sending pieces of masonry flying as she snaps a cable finish line. It is stylistically resonant with classic Mexican mural art, including a traditional glaze that made light appear to emanate from the masonry. The runner’s skin tone and facial features leave ethnic and racial identity to the viewer’s interpretation, allowing women from many backgrounds to see themselves breaking their own barriers. Behind her, golden light bathes a downtown cityscape with a group of women following at her heels.

That light disappeared in February 2019, when the mural was abruptly and mysteriously covered with multiple coats of light gray paint. At first no one stepped up to take responsibility for the mural’s destruction, but a couple of months later the L.A. County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) admitted that a graffiti abatement contractor working for their Freeway Beautification Program had hastily whitewashed it, failing to recognize that underneath the graffiti was an important work of art registered through the L.A. Department of Cultural Affairs and protected by the Visual Artists Rights Act. Such works are routinely subject to tagging, but SPARC has developed extensive technical expertise in removing destructive graffiti while preserving the integrity of the original art. It remains to be seen how extensive the damage is under all those layers of gray paint and graffiti, but SPARC has vowed to fully restore the work for the community. It’s what they do.

That thread of vulnerability is ever present in public art installations. Michele Martínez, who earned her MFA in visual arts at CSUN, works largely with glass, ceramics, and other delicate materials to create mosaics and murals in high-traffic spaces. The CSUN campus is home to Martínez’s graduate thesis project, Wall of Changes, installed at the Student Center Plaza. She recalls some nervousness while installing the 36- by 6-foot work, which includes ceramic tiles created in collaboration with over 100 students, staff, faculty, and community members. It all seemed so fragile. And yet, the fragility was intrinsic to the concept. Inspired by the small folk devotional paintings known as retablos, Martínez helped participants to design and create tiles about a moment of meaningful change in their personal lives. It was an enormous undertaking and Martínez is forever grateful to ceramics area head Patsy Cox, who made the studio and kilns available 24/7 for her marathon sessions. Twelve years on, the installation remains intact and undamaged.

Martínez, who early in her career worked with Judy Baca on The Guadalupe Mural Project in central California, is full of gratitude for the women who inspired her along the way. Women in public arts tend to support one another. It was while she was assisting multimedia artist Robin Strayhorn on a Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) project that Martínez was urged to submit her own project proposal to MTA. The MTA allocates 0.5% of station construction project budgets to the Metro Art program, which has commissioned over 300 projects since it was established in 1989. Artists are selected through a peer review process with community input. As Martínez worked with Strayhorn to construct and install sweeping concrete benches with colorful mosaics honoring the life and activism of Rosa Parks for the MTA Blue Line Willowbrook Station, Strayhorn told her the new San Fernando Valley Orange Line was accepting proposals. Martínez submitted and was selected to head up a project of her own design at the Orange Line’s Sepulveda Station in Van Nuys.

Martínez said she had that not-yet-completed commission in hand when she arrived at CSUN’s MFA public art program to study with Kim Abeles, whom she considers a role model. Abeles embraces the title artist-activist with work exploring biography, geography, feminism, and the environment, and she’s created major projects with the California Science Center, county agencies, and the National Park Service. Among many lessons Martínez learned from Abeles, she cites two: First, be your best self when you’re out there working in the world and commissions will likely follow. Second, “If you hear about a call for public art and an idea comes to mind, that idea wants to go somewhere.”

“Being a public artist isn’t for everyone,” Martínez says. “It means maintaining flexibility and sometimes throwing caution to the wind. Nine out of 10 proposals don’t make it, so you have to be an optimist.”

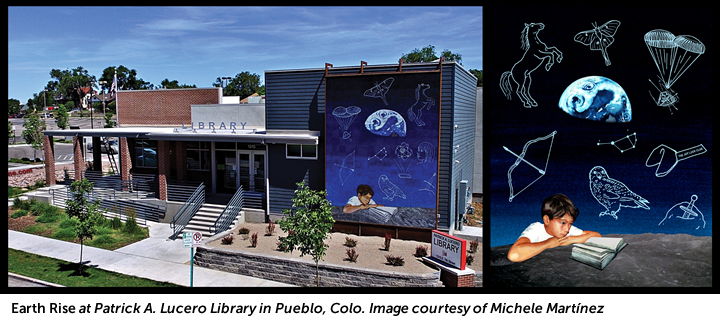

Martínez’s most ambitious project required a healthy dose of optimism. The city of Pueblo, Colorado’s Patrick A. Lucero Library building project put out a call for proposals to design art for its entrance portico. While Martínez is based in Los Angeles, she had relatives in Pueblo and had become intimate with the social and arts culture of the library’s historic eastside neighborhood when she worked there as a door knocker for the 2010 Census. She submitted and her design was selected: a 15- by 19-foot night sky mosaic with a rising earth and references to reading, nature, science, and space. The mosaic comprised nearly 300 square-foot sections containing 334,000 quarter-inch cubes made from salvaged window glass that she sintered and colored. Installation was no small feat, requiring steel fabrication for a support structure as well as architectural and engineering consults. She also needed a staging site, and the St. Leander Church across the street graciously offered its basement as a makeshift studio. Nearly two years in the making, Earth Rise was unveiled in July 2017 to a community who felt included and invested in the process from the start.

Asked about the most rewarding part of making public art, Martínez immediately cites interaction with the community where it’s installed. She noted an “electric” feeling at doing something for a specific community. Her goal is to make art that communicates and resonates with its site. That aforementioned MTA commission, completed while she was still an MFA student at CSUN, features a terrazzo mosaic on a westbound platform called “the Butterfly Cycle.” Adjacent is a porcelain-enameled steel wall mural featuring excerpts of Pablo Neruda poetry that grapple with attachment and loss in nomadic life, speaking to the many commuters who would pass through who might have been born elsewhere but were making new lives for themselves in the bustle of Los Angeles. The overarching title of the Sepulveda Station installation: Todos vuelven/Everyone Returns. Martínez told a story about the Orange Line’s opening day, when the MTA staged events highlighting the newly unveiled art across its route. As she rode the bus through the San Fernando Valley express corridor she talked to families and asked one little girl what her favorite part had been. “I like the one with the butterflies,” the girl grinned. It was a perfect moment for a public artist.

Betty Beaumont makes art that resonates with its environment while also highlighting elements lost to time or environmental degradation. Toronto-born and L.A.-raised, Beaumont earned her B.A. in art at CSUN before studying environmental design at the Berkeley School of Architecture. Those disciplines coalesce in installations that help reshape and rectify environments.

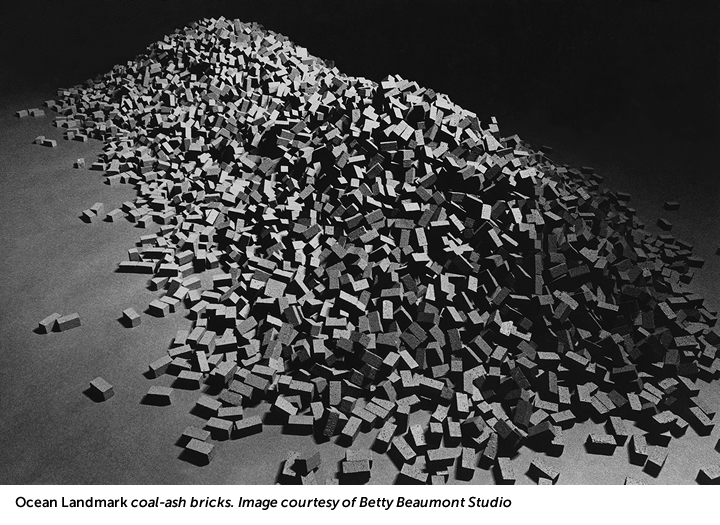

The now New York–based artist’s best-known work is the epic Ocean Landmark. Completed over two years and installed in 1980 on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean near the Fire Island National Seashore, the work was a collaborative effort of the artist, scientists, and engineers investigating environmentally sound ways to neutralize coal-ash waste. Beaumont proposed that they render the waste as inert bricks and deposit them in the ocean at a depth amenable to life and development of reef habitat. Her proposal was adopted and jointly sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy, the Smithsonian Institution, Bell Labs, and Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory. Beaumont’s project also received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the America the Beautiful Fund, Media Bureau, and in-kind contributions. Five hundred tons of coal waste were cast into 17,000 bricks, towed to a designated ocean coordinate, and released to settle as a mound on the ocean floor. Beaumont’s sculpture/reef exceeded expectations, transforming over the years into a thriving habitat for sea life that has since been designated as a “fish haven” on the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s coastal navigation map.

Ocean Landmark challenges traditional art categories, being a monumental yet essentially unviewable work. Beaumont has more recently turned toward very visible structures that highlight environmental and financial crises. Photography projects have documented proliferation of cell phone tower concealment strategies (in lieu of telecommunications companies addressing risk research and abatement), abandoned homes and businesses in the wake of the subprime mortgage disaster, and structures slated for demolition due to contamination by industrial toxic waste.

For the past five years Beaumont has been working on a project that highlights the tragedy of language attrition. She’s collecting audio recordings of songs in dormant languages with intention to broadcast them from an array of sound towers. The effect will be a visual and aural sensory experience that will challenge visitors to consider losses in cultural heritage when languages pass out of living memory. So far Beaumont has more than 400 recordings, but she had to put the project on hold during the pandemic, as her plans require a team of assistants as well as active collaboration with the relevant cultural groups.

Quarantine is hard on public artists. While there are certainly solitary aspects in the work, all of the major projects discussed here called on teams to fabricate, paint, assemble, consult, and more. In the meantime, Beaumont has pivoted to smaller studio pieces that can be completed in isolation. But all the artists continue to make designs and submit proposals for larger, more participatory works in the near future, when we can bring the public back to public art.