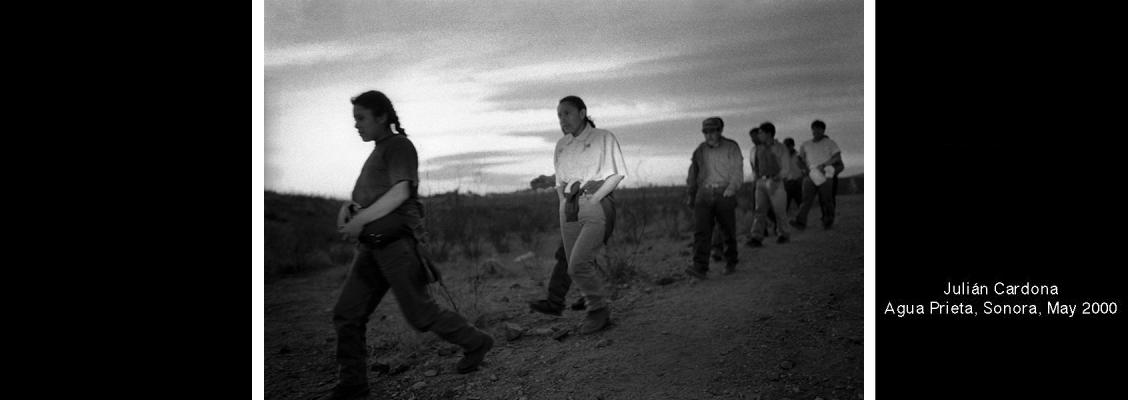

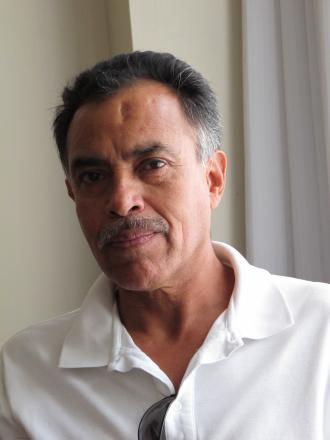

Julián Cardona's Commitment to Journalism

By Kent Kirkton, founder of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center

October 6, 2020—Julian was the epitome of a journalist. And we (Dr. Jose Luis Benavides and I) began to recognize this the first time that we met and interviewed him as the following conversation reveals

KK: You don’t think, as a journalist, you put yourself in riskier situations than the average citizens would?

Julian: I think journalism is, by definition, a risky profession. I used to think of me just as a journalist. Now the city is dangerous for everybody. If you do your job as a journalist it has always been difficult, going to war, going to dangerous places. That’s your job. You have to try to do it, try to do it well. I am not concerned about me. I am not the story.

KK: Chuck (Charles Bowden) reports in Murder City that the violence has become so capricious that it didn’t seem like you could take precautions any more that there were no longer any safe places in Juarez.

Julian. There is no safe place to go and the same thing can be said for many parts of Mexico. Juarez is, of course, the main place, the main dangerous place in the country. But I think you have to make a living and you have to stay in your city. You have to keep your friendships. And I feel happy to have a lot of friends. I think that is the part of my life that I have more friends during the most dangerous time in my city. I see many more people. I talk to more people.

KK: But Julian, you don’t have to stay in your city.

Julian: Why not.

KK: I am not saying you shouldn’t stay only that you don’t have to. You have made a commitment.

Julian: Yes. You make a commitment. But I am not the only one. There are many people who make a commitment. We may not have the answers but there are many people who have the same commitment. I have friends, reporters. I have activist friends who love the city.

We have interviewed many journalists who evoked the same notions (goals, aspirations.) However, when we reflected on the fact that we were sitting in the middle of what was at the time, the most dangerous city in the world his words began to take on a deeper meaning which have been many times over by his published work and the people who knew him best.

Julian first became known to us with the publication of “Juarez the laboratory of our future written by Charles Bowden with contributions by Noam Chomsky and Eduardo Galeano. It was published by Aperture books in1998. Julian was one of number of photographers that Bowden asked to participate in the publication, all of whom were colleagues of Julian’s. It was in addition to the prescient nature of the book, a significant moment because it led to a long association and collaborations between Julian and Bowden.

Their collaboration on “Juarez” was also the first strand in a web of friendships that eventually included Professor Molly Molloy, an author and research librarian, who maintains the Frontera List a huge repository of information about the border; Jose Galvan, known as El Pastor, who single handedly established and maintains an asylum for lost people on the outskirts of Juarez; and Alice Briggs, an artist/activist with whom Julian recently co-authored “Abecedario de Juarez,” an illustrated dictionary of a new language that has arisen in the violent streets of Juarez; as well as many and ongoing collaborations with Charles Bowden, journalist and author of approximately 30 books.

It was through this group of friends that we were able to meet Carlos and Sandra Spector, who have been working for years in El Paso helping legally asylum seekers from Mexico escaping what Carlos defines as “authorized crime.” The Spectors generously gave us access to preserve the testimonies of a good number of asylum seekers. And in Juárez, Julián introduced us to Casa Amiga and its director at the time, Irma Casas, who helped us identify important stories and preserve a big part of their in-take records.

It was through this group of friends that we were able to meet Carlos and Sandra Spector, who have been working for years in El Paso helping legally asylum seekers from Mexico escaping what Carlos defines as “authorized crime.” The Spectors generously gave us access to preserve the testimonies of a good number of asylum seekers. And in Juárez, Julián introduced us to Casa Amiga and its director at the time, Irma Casas, who helped us identify important stories and preserve a big part of their in-take records.

(On a personal note: Jose Luis and I have been fortunate enough to spend a good deal of time with and among this group of people. Those hours have consistently been the most intellectually and emotionally stimulating one can image. It is no wonder that such exceptional work arose from their interactions.)

These long and fruitful friendships also attest to Julian’s early notion that, “You have to keep your friends.” He also stated that, If you do your job as journalist, “You have to try to do it, dry to do it well. You make a commitment.”

His commitment to doing his job well is on clear view in “Exodus/Exodo” in which he collaborated with Bowden. Julian had been investigating immigration from a Mexican for many years as a reporter in Juarez and he wanted to know about what happened when the immigrants arrived and settled in the U.S. He conceived of his self-assigned story title as “The New Americans.” When he and Chuck discussed the idea, Chuck’s idea was that people were fleeing Mexico.

Over the course of the project they worked at examining both sides of the same coin. For Julian, he followed immigrants from their home and along the torturous paths to Otro Lado. He went to their homes and work places to see how they lived once in the U.S. He thought of them as new Americans, especially the children that were born here as they took their places in the social and economic life of the country.

He and Chuck managed to produce an extraordinary book that balanced two approaches to a subject so well that one would never have imagined that they started from two different perspective. For the most part, they worked independently while also traveling together on occasion and collaborating at the end of the project. (They resolved and age-old problem of how wordsmith and a photographer can be free to follow their own instincts and end up with a synchronous literary effort setting the bar for those who follow.)

Finally, consistent with his recognition of the role of a journalist in today’s society and the fading notion that shining a light on a problem is going to lead to a solution, Julian donated his lifelong work in photography to the Tom and Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge in hopes that in the future that people who want to know what really happened on the border in these tumultuous times could be informed by his work which includes three oral histories completed in 2012.

Commemorating the 36th Anniversary of the Death of American Photographer Richard Cross

By José Luis Benavides

June 21, 2019—Today, 36 years ago, American photojournalist Richard Cross and the Los Angeles Times’ bureau chief for Mexico and Central America, Dial Torgerson, were killed in a car struck by a land mine in Honduras, near the Nicaraguan border. They were covering the contra war. Cross was 33 years old and Torgerson was 55.

June 21, 2019—Today, 36 years ago, American photojournalist Richard Cross and the Los Angeles Times’ bureau chief for Mexico and Central America, Dial Torgerson, were killed in a car struck by a land mine in Honduras, near the Nicaraguan border. They were covering the contra war. Cross was 33 years old and Torgerson was 55.

Forty years ago, in June of 1979, Cross landed for the first time in a Central American country, Nicaragua. He was hired as a stringer for AP to cover the last offensive of the Sandinistas before the overthrow of dictator Anastasio Somoza. It was a transformative experience for a young photojournalist, who preferred to capture images of people, not leaders, in their struggle for liberation against an oppressive government. Later, when he prepared a selection of 76 photos to be published in a 1982 book co-authored with Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal, Nicaragua: la guerra de liberación, Cross put in writing his process for selecting the photos for that book. He didn’t want to portray newsworthy events, he didn’t want to create a visual chronology of the war, neither include press conferences, nor big leaders. He wanted to portray people not because of their idiosyncratic psychological identity, but because of their social (group) identity—in other words, he didn’t want to portray individuals, but archetypes of the Nicaraguan people.

Cross worked for several news organizations and covered the wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, and the refugee crisis in Chiapas, Mexico—the most visible symptom of a larger crisis that forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee to other Central America countries, Mexico, and the U.S. By the end of 1983, 46,000 of the 200,000 Guatemalans who had escaped to Mexico, Mayans most of them, were living in refugee camps in Chiapas. Guatemala’s military forces killed 150,000 Mayans on the suspicion of cooperating with the guerrillas. Over 400 massacres were documented by the Truth Commission between 1981 and 1983, some of which constituted what is legally defined as “acts of genocide.” In El Salvador, the United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees estimated that around a quarter of a million Salvadoran refugees were living in Mexico and other Central American countries in August of 1982. The following year, these estimates increased to 326,000, besides the half a million Salvadorans who were already living in the United States without papers.

At the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, we are getting ready to open an exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum of Social Justice of Richard Cross's work in Central America. We want to celebrate his life’s work and the fact that his photographs are now available for the public to see at the digital collections site of the California State University, Northridge’s Oviatt Library. In doing this exhibition (to open on August 15), we want to honor Cross’s commitment to the people in that region. For that reason, we titled the exhibition “Visualizing the People’s History: Richard Cross’s Images of the Central American Liberation Wars, 1979–1983.” We would love to see you there. Our work has been possible thanks to a grant by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Maxie L. Floyd, Jr. (1934–2019)

By José Luis Benavides

February 26, 2019—It is with great sadness that we learned about the passing of photographer Maxie Lee Floyd, Jr. last February 11. Floyd was born on January 12, 1934, in Temple, Texas. His family moved to Los Angeles, where he attended the 36thSt. Elementary, Foshay Jr. High, and Polytechnic High School. During that time, he developed a strong interest in football and track. After finishing high school, he attended Los Angeles City College and the University of Southern California. Floyd served in the United States Army as military police in Fort Lewis, Washington. He was a very successful salesman for the National Distribution Company and he was also president of Huckster International, an association of liquor salesmen.

Maxie Floyd was an award-winning photographer who began his career over 40 years ago. Self-taught, Floyd’s work has been exhibited at the Black Gallery, UCLA, Duke Ellington’s Centennial Celebration, The Museum of African American Art, William Grant Still Center, Mt. San Antonio College, the Queen Mary, and the art venues of the Monterey Jazz Festival. Floyd was a founding member and vice-president of The Jazz Photographers Association of Southern California. He received the Los Angeles Jazz Society Annual Tribute Award for his photographic work.

Floyd’s philosophy on photography was something he compared to the lone athlete running a race—one race at a time, one photograph at a time. He photographed, among others, international jazz luminaries Bo Diddley, Chuck Mangione, Flora Purim, Nancy Wilson, Dizzy Gillespie, Michael Petrucianni, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Miles Davis, Gerald Wilson, Ray Charles, Herbie Hancock, Lionel Hampton, Chick Corea.

Richard Cross's Photo Digital Collection goes live

January 29, 2019—CSUN's Tom & Ethel Bradley Center and the Oviatt Library have put live Richard Cross's digital collection site with the first group of 1,410 images of Central America (1979-1983). We will continue uploading new photos throughout the year.

El Centro Tom & Ethel Bradley de CSUN y la Biblioteca Oviatt han puesto en marcha el sitio de la colección digital de Richard Cross con el primer grupo de 1,410 imágenes de Centroamérica (1979-1983). Seguiremos subiendo nuevas fotos durante todo el año.

The Beat on 1 interviews Keith Rice

January 27, 2019—Last Monday, Jan. 21, Spectrum's The Beat on 1's Lisa McRee, Melvin Robert, and Giselle Fernández conducted an interview with Keith Rice, the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center's historian and archivist on the significance of the Tom & Ethel Bradley's collection of images by African American photographers from Los Angeles preserving the visual history of Martin Luther King and the residents of Los Angeles.

John Kouns (1929–2019)

By José Luis Benavides

January 21, 2019— The Tom & Ethel Bradley Center regrets to inform the passing of photographer John Kouns on Saturday, January 5, 2019, in Sausalito, California. Kouns (1929–2019) was not only an accomplished photographer but also an outstanding and generous human being who fought for social justice.

His images, housed at the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, are meant to document people’s history. They portray people making history by struggling for worker’s rights, for civil rights, and for social justice. Above all, they portray people that hoped for a better future for their country.

A self-described “concerned photographer,” Kouns’s images open an intimate window to the work of these anonymous history makers. He spent years documenting two of the most important social movements of the 1960s and 1970s in America—the civil rights struggle in the South and the worker’s and civil rights struggle of the United Farm Workers Union in California.

Born in Alameda, California, on Sept. 21, 1929, John Alexander Kouns grew up in San José. A high-school teacher introduced him to Richard Wright’s novel Native Son, a book that shaped Kouns’s perspective on race in America. “It affected me tremendously,” said Kouns. After finishing the book, he went and ask his teacher what he could do. “John,” the teacher said, “what you should do is belong to the NAACP.” And that’s exactly what he did. He joined the organization at age 15.

In the late 1950s, Kouns studied at New York Institute of Photography where he met and got inspired by Eugene (Gene) Smith. After working for a couple of years for UPI in San Francisco, he became a successful industrial photographer who practice, on the side, what he described as Social Work Photography, a free-of-charge work for agencies on deaf and handicapped, the blind, and the Salvation Army.

In 1963, he decided to give himself a “self-imposed Guggenheim in the South” as a prelude to a plan to visit the South. He traveled to the March on Washington where he took photographs of the participants. Later, while he was in Birmingham, he photographed the aftermath of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four girls. In Selma, he photographed the struggle for civil rights from 1963 to 1965, including two of the three marches from Selma to Montgomery.

Later, Kouns went to California’s San Joaquín Valley because the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) was trying to unionize farmworkers and he wanted to photograph that process. He ended up staying with the workers and continue following the struggle of Filipino and Mexican-American farmworkers during the 1960s and 1970s.

Here is a short video with some of his images during an oral history interview conducted by James Moore in 2004 as part of his MA thesis work at California State University, Northridge.

Who is Richard Cross?

By Pilar de Haro

A couple of months have passed since I began working on the Richard Cross collection at the Tom and Ethel Bradley Center, at California State University, Northridge. As a technical archivist, my role is to preserve and digitize photographs and provide supporting metadata and research for each photo. Although metadata can be limiting based on photographer notes and what I can find to corroborate names, events, and people --research is the best part of metadata.

Richard Cross was a photojournalist who documented the wars and genocides in Central America in the 1980s. He freelanced for news outlets including the AP, Newsweek, U.S. News & World Report, and others during his visits to Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. He was a young guy traveling to dangerous places to take photographs.

My immersion into the Richard Cross collection has led me to learn more about him, and understand his approach as a photographer and visual anthropologist. My mentor here found a snippet of his handwritten notes, that was titled, “Why risk life” which lists four reasons:

1. “Social Concern”

Cross writes, “This came as a result of living in a third world country for 5 years and experiencing first-hand the poor and class struggle.”

2. “Practical”

“Since photojournalists is medium and committed to and trained for, and since I am not adequately wealthy, I must make a living from this visual medium,” said Cross, in his notes.

3. “Adventure”

He writes, “Escape the boredom and alienation one feel(s) in U.S. society.”

4. “What does El Salvador have to with the U.S.?”

“Photographing war in Central America, for me has to do not only with getting good shots which tell the news at the moment, but also with getting pictures which, when joined with other images and text, tell a story which reflects a more systematic and synthetic approach to the situation. An approach which is perhaps more historical because it attempts to show relationships existing between the present and the past,” wrote Cross.

In the next couple of months, I plan to advance my research by learning more about the personal stories and historical context of the Central American revolutions through the lens of Richard Cross.