*

This file is under construction.

It is being converted from a scanned document into a more useful

format. Paragraphs in BLACK have been

converted and proofread at least once. Paragraphs in RED have not been converted and proofread..

Lary

M. Dilsaver

University of South Alabama

William

Wyckoff

Montana State University

William

L. Preston

California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo

Contents

Fifteen Events

That Have Shaped California’s Human Landscape. 1

Introduction. 3

Settlement by the First Peoples, 15,000 Years Ago. 4

Cabrillo’s Landfall at San Diego, September 28, 1542. 5

The Discovery of Gold at Sutter’s Mill, January 24, 1848. 8

Initiation of the U.S. Public: Land Survey, July 17, 1851. 10

San Francisco Takes Water from Lobos Creek, September 17,

1888. 13

Creation of Suburbs, 1864. 14

Yosemite State (and National) Park, June 10, 1864. 17

The Coming of the Transcontinental Railroad, May 10, 1869. 19

Electrifcation of Market Street, April 9, 1874. 21

Passage of the Wright Irrigation Oisto·id Ad,Mardt 7, 11187. 23

San Gabriel Timberland Reserve, December 20, 1892. 28

Sa1e of First Ford Model T,1903. 30

Wartime Buildup Begins, June, 1918. 33

National Environmental PoUc:y Ac:lyJanua ry 1, 1970. 35

Production of the Intel 8080 Microproecssor, December, 1973. 38

Conclusion. 40

The

year 2000 has many meanings for the people of California. Aside from the celebration and cerebration

occasioned by the end of the century and the millennium, it is the

sesquicentennial; of the state. It is

fitting then that among the numerous chronological analyses and rosters of

greatness accompanying the passage of the twentieth century, we reflect on

California and what kind of place it has become. Although many scholars, pundits, and personalities

have included California in their local and regional reviews, there has been

little attention to the historical geography of the state’s human legacy. With this article we hope to begin the

remediation of that deficiency.

We

have chosen to present the fifteen events that have most affected the human

landscape of California. The geographic

concept “landscape” means the visual “look of the land” as used by the German

geographer Otto Schluter and defined for American geographers by Carl Sauer

(1925) in his seminal article “The Morphology of the Landscape.” Indeed, Sauer

began a tradition of cultural landscape study that shaped much of twentieth

century cultural geography in the United States. Lowenthal and Prince (1964) provided the best

expression of the approach used in this article with their definition of the

landscape as a palimpsest in “The English Landscape.” Humans have inhabited California

for at least 150 centuries, possibly more.

Each generation has altered the landscape. However, all but the first began from a base

of earlier human modification. Some

changes came close to sweeping away earlier patterns. Not one completely erased those patterns. The cumulative effect of their activities has

altered and humanized the appearance and the substance of the state’s diverse natural

environments. These changes can be detected

at any scale, from the pedestrian’s viewscape to the California filmed from the

space shuttle.

The

human impact on the landscape is apparent in both what is present in a scene

and what is absent. Cities, roads, farm

fields, and channeled streams are deliberate impositions. The legacy of human error and improvidence is

also evident. Vegetation change stems

from accidental introduction of exotics or indirectly from alteration of the

fauna as well as from burning and clearing.

Even the persistence of a vegetation community often reflects deliberate

decision to preserve selected resources.

Geographers

do not often use specific events to explain the landscape and the human agency

acting upon it. However, it can be a

useful heuristic device. In the centuries

of continuous human activity in California, certain processes have had the

greatest cumulative impact. We choose to

identify the fifteen punctuations of the state’s timeline that began the most

influential processes. Where a process

such as the use of automobiles began elsewhere, we have generally chosen its

arrival in California as our event. These

processes, in turn, spawned related but independent processes and exerted both direct

and indirect impacts. Thus, the arrival

of the automobile directly set off the processes of large-scale road building, oil

drilling expansion of tourism, and the remaking of urban places. Indirectly, pollution from cars has impacted

natural scenes by harming vegetation from the coastline to the Sierra Nevada

and beyond.

One

of the difficulties in choosing fifteen events was deciding which stand apart

from the ongoing intertwined processes of human occupation. One could argue that the arrival of humans

was the main event and the rest followed as a matter of course. In each event we try to show a compelling

break from the trend of human activity and elucidate its direct and derivative

processes. Thus, the establishment of

wilderness areas in the state does not stand apart. It results from the creation of national forests

and the policies of land management that evolved to protect and use them. Alternatively, some forms of irrigation preceded

the Spanish, but the Wright Irrigation District Act enabled projects on a scale

so pervasive that it serves as separate event and process.

Why

fifteen events? There is a precedent for the number. Historian Rockwell D. Hunt (1958), in four consecutive

numbers of the Southern California Quarterly,

published “The Fifteen Decisive Events of California History.” He explained thathe based the number on Sir

Edward Creasy’s The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World from Marathon to Waterloo

(1851). We concur with Hunt’s statement that:

Certainly there is

no magic in the number fifteen-it is simply a convenient number that has

because suggested by Creasy; large enough to afford a respectable variety of

phases in human events...sufficiently small to avoid the pitfalls of particularism

(4).

We

hope to satisfy two ends with this essay.

First, we reiterate that this not a definitive statement. Instead we hope this is the beginning of a scholarly

debate. Most likely, everyone who reads

this will disagree with at least one or two of our choices. We encourage all to challenge our analysis and,

in so doing further historical geographic inquiry about the Golden State. Second, this article may serve as a ready paradigm

for teaching geography at the K through 12 grade levels. The type of diagnostic landscape analysis we

employ is eminently useful for getting students to reflect on the reality of

geographic themes in the scenes that they view.

Each student can choose an area and evaluate how important these events

or any others have been in shaping the landscape.

We

believe the following fifteen events began processes that have had the greatest

impact over the widest area on the visual appearance of California’s landscape. The first two are the arrivals of the first

people thousands of years ago and the Spanish nearly five centuries ago. The pervasive influence of the American

cultural legacy can be divided into four categories. The imposition of settlement form includes

the initiation of the rectangular land survey and the earliest suburbs. Economic development came with the discovery

of gold, the diversion of water to cities, the establishment of irrigation

districts, and World War II. Looming

large throughout the landscape are technological innovations including the

railroad, heralded by the arrival of the transcontinental line,

electrification, the appearance of mass produced automobiles, and the invention

of the Intel 8080 microprocessor leading to the personal computer revolution. Finally, the feverish expansion of

development has been blunted or shaped by three signal events in conservation. These are the establishment of Yosemite, grandfather

to all national and state parks in California, the creation of forest reserves,

today’s national forests, and the passage of the National Environmental Policy

Act. We have chosen them based on their

impacts throughout the continuum of scale.

Some effects are most apparent to the individual on the ground. Others impact the tapestry that is the entire

state, accounting for both the range and spatial distribution of human

phenomena. We present them in

chronological order beginning with the most fundamental event of them all.

Landscapes

in California have been dramatically altered and shaped by humans for at least

fifteen millennia. Indeed, approximately

15,000 years ago people settled permanently in California and began humanizing

processes that are revealed in the state’s contemporary settings. The aboriginal legacy is observed most readily

in the wild lands of California but is expressed as well among settled

landscapes.

California

was sporadically visited during the initial migrations that introduced Old

World humans to the Western Hemisphere. This

period coincided with the last glacial, or Late

Wisconsin, stage of the Pleistocene epoch.

By 15,000 years ago, descendants of these first migrants accompanied by

more recent arrivals from the Old World, came to stay

and make California their permanent home.

They trave1ed to the area of the future state by both land and sea and

adapted to environments governed exclusively by natural processes (Erlandson et

al. 1996).

At

the same time, California was experiencing rapid climate-induced changes as the

glacial period subsided and the transition to modern or Holocene conditions

progressed. Despite these environmental

fluctuations, the first permanent settlers skillfully and successfully adapted

previous lifeways to a variety of habitats within California. Immigrants who arrived by sea initially subsisted

on plants, small terrestrial animals, and marine life that thrived along

California’s coast (Jones 2000). Those who

entered California by land were accustomed to big game hunting as a means of

survival. They discovered a fertile

setting for their traditional economic pursuits owing to the state’s diverse

assemblage of late Ice Age megafauna. Due

to the hunters’ skill as well as the animals’ inexperience with human predators,

approximately 75 percent of the larger (100 pounds or more at maturity) genera

of game animals were liquidated within a few thousand years (Martin 1984, 258). As a consequence, subsequent human residents inherited

a relatively impoverished zoogeographical landscape where such animals as

mammoths, saber toothed cats, and ground sloths were no longer part of the

biota. One can only conjecture what

portion of the megafauna would have survived to the historic period had these

hunters not come when they did. However,

the composition of the contemporary fauna and the structure of associated habitats

would be markedly different (Owen-Smith 1987).

Owing

in part to the substantial reduction of the state’s large game, Native

Californians redirected their predation to the remaining fauna and intensified

their utilization of the state’s impressive array of plants. Although few large species were driven to

extinction after 6000 years ago, favored marine and terrestrial animals were

locally decreased by hunting to the point that they became insignificant in

aboriginal diets and resource areas (Broughton 1994, 372; Douros 1993, 557-58). These animals include various pinnipeds, otters,

bears, beavers, and ungulates such as elk, antelope, and deer.

Ancient

animal depletions and extinctions continue to influence contemporary landscape

expressions in myriad ways. The

structure and species content of ecosystems are determined from the bottom up

by flora that is largely an expression of climate and also from the top down through

the actions of animals. A change in any

one of these factors results in alterations that cascade through much of, if not

the entire, ecosystem (Huntly 1995). The

relationship between otters and kelp beds provides an example. California’s kelp bed habitats are dependent on

solar energy as well as upon otters that prey on sea urchins that, in turn destroy

kelp. The removal or reduction of sea Otters

by humans will unleash alterations that ripple through the kelp habitat (Estes et

al. l978). Every terrestrial animal, to a greater or

lesser extent, also exhibits analogous engineering roles in their respective

ecosystems. The elimination of at least

75 percent of the megafauna and the subsequent reductions in the spatial and numerical

presence of surviving wildlife by California’s first peoples yielded

environmental changes that are interwoven into the character of the state’s

contemporary aquatic and terrestrial landscapes (Lawton and Jones 1995, 141).

Pre-Columbian

people also contributed to the con temporary presence of certain animals by

transporting species to alien habitats. The

introduction of foxes to the Channel Islands by Native Californians is one

example (Schoenherr 1992, 708-09). The intentional

modification of vegetation communities by fire and other means further altered

animal demographics and distributions by increasing or decreasing the carrying

capacity of some habitats. For example,

the expansion of grassy prairies in the redwood forests of northwestern

California increased the carrying capacity for preferred animals like deer

(Dasmann 1994, 19; Lewis and Ferguson 1999, 167-68). These modifications then

rebounded onto the vegetation communities due to the resulting increases or

decreases of these animals’ engineering influence.

Due primarily to population pressure

and the depletion of large game, Native Californians compensated by using a host

of techniques to increase their vegetative resources.

These included the applications of fire, pruning, coppicing,

weeding, transplanting, and broadcasting (Blackburn and Anderson 1993). Where the first Californians used these

practices on a sustained basis, they markedly restructured landscapes and

altered their species content.

Sustained burning reduced understory

in both coastal and inland woodlands. In

frequently burned oak groves, a spacing of single oaks developed that later

colonial people described as “oak park woodlands” (Anderson and Morratto 1996,

200; Rossi 1979, 84-90). Furthermore, the

distribution of chaparral associations on coastal and interior hill slopes

still reflects the ancient effects of anthropomorphic fire (Schoenherr 1992, 28-362). At higher elevations in the Sierra Nevada and

Cascade ranges, intentional aboriginal burning complemented lightning fires in

allowing the expansion of fire-dependent forest trees such as ponderosa pine

and sequoias. Indeed, everywhere in the state’s

lowlands where human-set fires were common, grasslands expanded at the expense

of brush and woods (Bakker 1971, 168-69, 186).

In

some locations, native peoples augmented fire with other horticultural techniques

to improve the quality and abundance of floral resources. Plant species were both intentionally and unintentionally

disseminated by broadcasting and transplanting as well as through processing

and storage. For example, many of the

oak trees observed around bedrock mortar sites result from acorns the Native

Californians transported there (Anderson et al. 1997, 37-38; Bonnicksen et al. 2000,

453). These practices had consequences

that extended beyond the organic world. For

instance, intense management by native peoples increased and made more reliable

local water yields (Biswell1989, 156; Shipek 1993). Colonial processes curtailed and quickly terminated

native people’s manipulation of vegetation.

Nevertheless, over thousands of years Native Californians shaped the

organic stage on which these subsequent, often extreme, developments occurred. Their ancestral practices thus remain integrated

in various degrees within the fabric of many contemporary wild lands (Anderson

and Moratto 1996, 194). Modern land managers

in government reserves like Sequoia National Park have adopted one of these

ancient practices, prescribed burning (Biswell 1989).

The

heritage of Native Californians is also manifest in a variety of settled

landscapes. Historically, the altered

aboriginal territories first observed by European and North American explorers

helped formulate impressions of the settlement and economic opportunities in

the region. These initial

interpretations had bearing on the eventual geography and economy of coastal

settlement by the Spanish. The siting of missions and the associated infrastructure

of roads, ports, presidios, and pueblos are cases in point (Butzer 1990, 50;

Hornbeck 1983, 4045). Albeit not as

pervasive, a variety of prehistoric cultural settings endure

in many locations and influence modern landscapes. For example, portions of many roads and highways

follow ancient aboriginal pathways (Davis 1961).

Remnants

of native settlements, resource processing areas, art work, and battle sites

accentuate the rural environs of nearly every county, and at times provide

destinations for tourists. These include

Captain Jack’s (Kientpoos) stronghold in Lava Beds National Monument in Modoc

County and Indian Grinding Rock State Park in Amador County. Furthermore, nearly every one of the state’s

missions, presidios, and military forts boasts Native Californian interpretive

components (Eargle 1993 155-79). Roadside

businesses, signs, and interpretive centers are just few of the landscape

features generated to entice visitors to these locations.

The

contemporary descendants of California’s first people also have a measurable and

growing impact on the state’s landscape.

More than a quarter of a million Native Americans populate the state in

the year 2000 and their numbers continue to grow. Many of these people live on

over one-half million acres of tribal lands that are distributed in more than

100 locations (Peters et al. 1999, 180-83). Beginning in the 1980s, gaming casinos began

to proliferate on tribal lands and number more than forty at present. They lure thousands of visitors and generate

unparalleled wealth for various Native California groups. A portion of the earned revenue has been

invested in infrastructure additions and improvements on tribal lands. In addition, native peoples hold an

impressive number of festivals, dances, powwows, and other events on and off tribal

lands that are open to the public (Eargle 1993, 180-83). All of these attractions have spawned an

increasing presence of lodging, advertising, and other business opportunities

in their vicinities. These most modern additions

combine with the millennia of alterations that have permanently affected

California’s human landscape to belie the familiar axiom that colonial peoples

erased the Native Californian legacy from the earth.

Not

long after the legions of Cortez laid siege to the Valley of Mexico in 1519,

Old World peoples and organisms began to probe California’s frontiers. The earliest substantial visitation was the voyage

of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542-1543.

Cabrillo’s exploration along California’s coast initiated

landscape-altering processes that equaled if not surpassed those of the first

people at the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

Cabrillo

and his crews did not establish permanent settlements. However, his and other foreign explorations

unwittingly introduced Old World germs and weeds to California during the

period prior to the founding of the first mission 1769 (Erlandson and Bartoy

1995; 1996; Preston 1996; 2001). These

organisms persisted, became naturalized, and radically changed the nature of

land and life over much of the state. Afterwards,

colonial settlers augmented these unintentional processes with conscious

introductions of alien attitudes, settlement frameworks, a wide variety of

domesticated plants and animals.

Californians

and their environmental relationships were especially vulnerable to the exotic

contagion that accompanied pre-mission explorations and colonial settlement

(Preston 1996, 20-22). Diseases such as

smallpox, measles, malaria, and virulent forms of syphilis progressively reduced

native populations and destroyed traditional land use practices. As a consequence of reduced human predation,

maritime and terrestrial game exploded in numbers and expanded spatially within

native resource areas. Furthermore, native

horticultural and associated practices such as burning, transplanting, and plant

processing were disrupted and eventually terminated. These alterations resulted in more brushy

understories in forests, changes in the distributions of some fire dependent

plants, and extensive soil erosion caused by greater numbers of ungulates

(McCarthy 1993, 223; McCullough 1997, 69; Preston 1997, 269-70, 277-81). In every environment where Native

Californians were diminished or eliminated as top predator and keystone species,

organic, hydrologic, and geologic aspects of the supporting ecosystem were

altered (Garrott et al. 1993, 946).

The

periodic forays to the state by foreigners prior to missionization also

conveyed Old World weeds like wild oats and other Mediterranean annuals that

spread rapidly and extensively at the expense of native species (Mensing and Byrne

1999). The transformation of California’s

floral landscapes continued unabated during the colonial period. Indeed, Cabrillo and his associates initiated

a process of botanical replacement that is still in progress today. As a result, approximately eighty to ninety percent

of California’s contemporary grass and shrub lands are now covered with exotic

plants, and about 17 percent of all plant species growing wild in the state are

of non-native origin (Blumler 1995, 310; Stein et al. 2000, 135). Elna Bakker (1971, 149) stated that, ‘this

successful invasion is one of the most striking examples of its kind to be

found anywhere.” Alterations of

California’s other visual signatures abound, most notably the golden color of

the grasses that lie beneath the state’s oak groves during dry seasons. Californians deem it a quintessential characteristic

of the state’s natural heritage. However,

prior to the arrival of Cabrillo, these same vistas displayed greener hues

owing to the prominence of indigenous perennial grasses. Furthermore, the regeneration capacity and

current distribution of many of the oaks in these settings are influenced by

greater soil moisture losses and an increased presence of rodents afforded by

exotic grasses (Griffin 1980; Danielsen 1990, 59). The widespread encroachment of Old World

invasives such as tumble weeds also influences the diversity and distribution

of a wide selection of plants and animals that occupy California’s roadsides and

wildland habitats. Relative differences

in seasonal coverage and soil holding capacities between exotic grasses and indigenous

species also have caused changes in runoff and associated soil erosion that

have modified the appearance of some watersheds.

In addition to these

unintentional invasives, Spanish exploration led to the introduction of a variety

of domesticated plants and animals that comprise much of the state’s contemporary

agricultural landscape. Although Native

Californians cultivated a small number of food plants, modern agriculture in

the state began with the first permanent settlement at San Diego in 1769 (Bolton

1949, 165, 174). An impressive array of

Old and New World crops such as grapes, maize, wheat olives, and citrus were

cultivated around the missions, pueblos, and presidios (Fig. 1) (Bryant 1967, 282,

316; Hornbeck 1983, 52-53). Later,

Mexicans and Americans took note of these successful Spanish plantings and

disseminated the crops and practices more widely throughout the state.

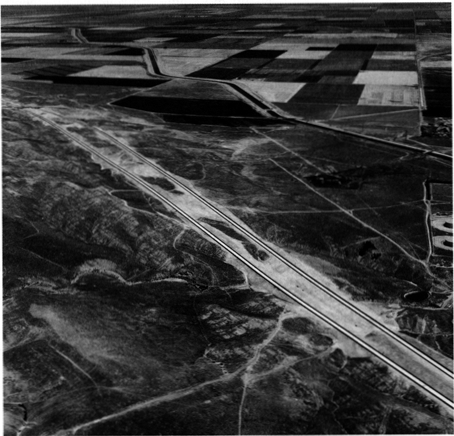

Figure 1. Mediterranean

grasses sweep down to an orange grove on Highway 180 near the Sierra Nevada

foothills. The influence of the Spanish

extends well beyond the areas they actively settled and used. Photograph by W. Preston.

Colonial

peoples also carried domesticated animals such as cattle, horses, sheep, and

fowl to California. Livestock numbers

quickly grew to enormous proportions in the mission realm and spread into the

state’s interior (Hornbeck 1983, 54-55).The impacts of these animals on plants,

animals, soils, and watersheds were additive to the changes wrought by the disruptions

of wildlife (Burcham 1957, 186-88; Schoenherr 1992, 718). Periodic droughts exacerbated the devegetation

and soil erosion caused by overstocked ranges (McCullough 1969, 15). Today, the residuals of these effects are

still observed in much of the gullying found in the coastal ranges and on the

margins of the Central Valley (Latta 1936).

The

presence of colonial livestock influenced subsequent economic pursuits and

their contemporary landscape expressions.

Owing to the Spanish and Mexican preference for domesticated animals as

well as their late colonial ubiquity, many early Americans viewed much of the

state as suitable only for livestock ranching.

As a result, the San Joaquin Valley was initially utilized as a great unregulated

pasture (Preston 1981, 86-87). Many of

the state’s lowlands have now been subsumed by other economic pursuits;

however, the legacy of traditional livestock ranching remains visible in

contemporary landscapes. One fifth of

the state’s land is currently used for grazing livestock (Peters et al. 1998, 302) and their terraced trails show

prominently on hillside lands. Barns, fences,

and corrals are ubiquitous in many rural areas.

California’s long history of ranching has altered a variety of physical

environments that range from valley riparian areas to mountain meadows in the

Sierra Nevada. The livestock industry accounts

for the alfalfa and some of the feed such as yellow corn,

that grace the state’s agricultural regions. Furthermore, livestock raising

has directly contributed to the presence of thousands of small dams, ponds, and

wells that appear on rangelands. Indeed,

agriculture is the foremost consumer of fresh water in the state and the

livestock industry demands the largest share of it (California Department of

Water Resources 1998, 4-26).

The

origin of many of the altitudes, practices, and institutions that have contributed

to California’s evolving landscape can also be traced to the colonial of the

Spanish. The Spanish as well as other foreign

peoples arrived in the state with environmental attitudes that were considered different

from those of the native inhabitants (Preston 1997, 264).

They

viewed the state’s physical resources initially as inexhaustible and entirely divorced

from their own spiritual existence. As a

consequence, colonial people possessed few inhibitions about changing the

physical environment for the purposes of settlement, economics, and sport. Both sustained commercial forestry and irrigation

began in the colonial period (Clar 1959, 12-44; Hornbeck 1963, 51-53). Furthermore, some of the rules that governed

the exploitation of natural resources survived to influence post-colonial

landscapes. As David Hornbeck (1990, 51,

60) explains, the “principles of mining, irrigation, water, and property rights

of women stem from the Spanish regime...and the large corporate farmers of

California share in a common water-rights system that is a thinly disguised copy

of Spanish water law. Indeed, the state’s

ultimate adoption of “the doctrine of prior appropriation” as the legal framework

for water use resembled the Spanish water law and allowed for the vast irrigated

landscape currently observed (Hundley 1992, 72).

The

initial Hispanic settlement infrastructure is also strongly reflected in California’s

contemporary pattern of roads, settlements, tourist destinations, property

boundaries, and architecture. A number of

colonial transportation pathways provide routes for important highways and roads. The conformance of Highway 101 with long

portions of El Camino Real is a noteworthy example. The pueblos, missions, and presidios served

as nuclei for most of California’s largest urban areas. Today over seventy percent of the state’s

population live in one of the twenty-eight sites originally founded by Spain

(Hornbeck 1990, 61). Many of California’s

twenty-one missions are important tourist destinations and they generate a host

of landscape elements in the form of advertising and urban and roadside

businesses. Furthermore, portions of the

boundaries of many of the hundreds of ranchos that were granted during the

colonial period have influenced the spatial patterns of countless urban and

rural roads, fences, trees, power lines, and town boundaries in coastal regions

such as the Santa Clara Valley (Broek 1932, 86, 94).

Most

of the foregoing landscape expressions of California’s colonial past are restricted

to the western portion of the state. However,

the adoption of colonial themes in built environments is more spatially

pervasive. The aesthetics of the Hispanic

architectural legacy (e.g. mission revival, arroyo culture, and ranch-style

houses) are significant and increasingly common attributes of domestic and commercial

landscapes (Pitt 1970, 29l-96; Starr 1973, 390-414; Rice et al. 1996, 165). Housing tracts replete with red tile roofs

and Hispanic decor for fast food outlets and banks are typical examples of the

heritage, appeal, and timelessness of the state’s colonial legacy. (Figure 2) Also in many rural and urban areas are

signature elements of a cultural scene created by todays Hispanic residents. Although most settled California after it became

American, they represent continuity in Spanish heritage that lies heavily on

the visible landscape.

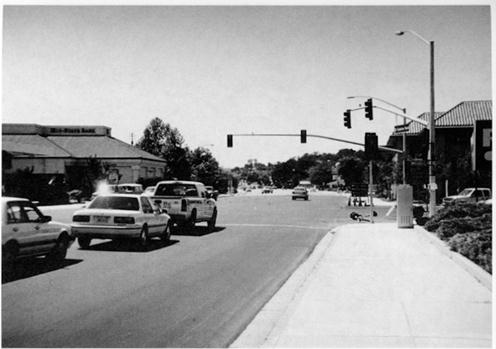

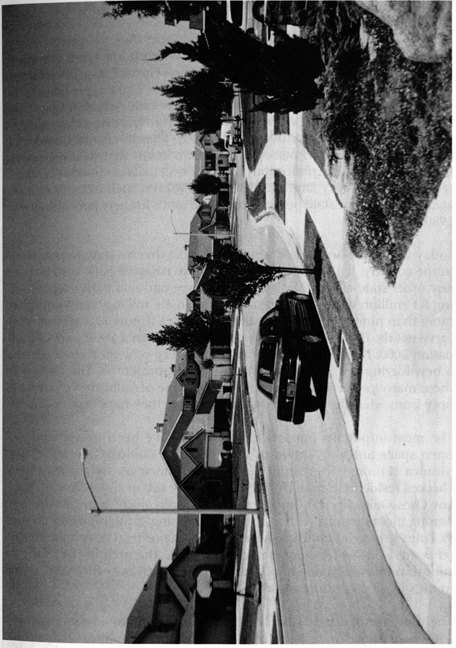

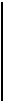

Figure 2. The use of El Camino Real as a modern highway and Spanish

style roofing in late twentieth century architecture are two persistent

landscape legacies of Spain shown here in Atascadero. Photograph by W. Preston.

Figure 2.

The use of El Camino Real as a modern highway and Spanish style roofing in late

twentieth century architecture are two persistent landscape legacies of Spain

shown here in Atascadero. Photograph by

W. Preston.

The

story of the California Gold Rush with its compelling and romantic character is

one of the most exhaustively researched topics in the West. Its inauspicious start, its ephemeral and unbalanced

economic focus, and the mania that drew 250,000 people to the state in less

than three years have become part folklore, part cultural genealogy (Gressley

1999; Holliday 1999; Paul 1947; Rohrbough 1997). Nobody denies its profound historical consequences

not only for the region, but also for the nation and the world. Yet, two years ago, on the occasion of its

sesquicentennial, several historians disputed its lasting effects on the modern

state. Richard White (1998) posited that

its immediate effects were superseded by later economic, demographic, and

political processes. Others added that

the transport, agriculture, and industry it brought would have come anyway to such

a resource rich state (Bethel 1998). However,

the discovery of gold ignited processes of economic development, settlement,

environmental modification, and political adaptation that have spatial and

visual resonance in California’s landscape of today.

The

most recognizable landscape legacies of the mining era are the mines, towns,

water systems, and transport links that litter the foothill and desert districts

of the state. Mining directly established

the settlement framework in those otherwise undesirable nineteenth century

locations. In Amador, El Dorado, Nevada,

and Placer counties, the major towns, including all four county seats, and the

roads that link them, began as parts of the gold rush infrastructure (Dilsaver

1982, 400-103). The historic character

of towns like Auburn, Nevada City, Sutter Creek, and Sonora has made the Sierra

foot hills the fastest growing part of the state (Figure 3). Even abandoned towns, like Bodie and

Columbia, entertain thousands of tourists and sustain a nostalgic idyll that

draws the new rush of mobile workers and retirees. Mining towns are among the most recognized of

historic landscapes in the country. They

display a convoluted morphology and historical authenticity that stem from

their adaptation to geomorphology and their unsuitability to functions other

than tourism and telecommerce.

The

abandoned infrastructure of mining is also present in these zones. The ruins of conveyors, mills, sluices, and

equipment, and tell-tale piles of debris spotlight thousands of former

mines. Due to their structural

instability and the frequent presence of dangerous chemicals, state and federal

agencies seek to identify and rehabilitate these sites. The Bureau of Land Management

(1996) estimates that its lands alone (13.8% of the state) contain 11,500 “Abandoned

Mine Land” sites. Miners dug or constructed

more than 7000 miles of ditches and flumes, among the earliest in the state. In many cases these also lay in ruins. However, these early water engineers also included

sources and water transport routes in the mountains that have been adapted for modern

use by towns and agriculture (Rohe 1983).

Their accession to high mountain water sources

and elaborate distribution systems helped pave the way for California’s

adoption of appropriation and massive agricultural irrigation a few decades

later.

Mining

also helped plot the settlement pattern and urban character of California. Gold

mining established the relative importance of Sacramento, San Francisco, and

Stockton. Sacramento became the state

capital based on its role as a mining supply center. San Francisco dominated banking and mining

finance. The presence of mining wealth

drew entrepreneurs who brought the state’s earliest industry to the Bay Area

and shaped its characteristics of light to medium assembly and consumer products

(St. Clair 1998).The crowded and vertical financial district of today’s San

Francisco lies atop sunken gold rush ships.

Limerick (1998) suggests that California’s urban focused population also

stems from the entrepreneurship and manufacturing derived from the mining industry. Furthermore, the distinctive Asian landscapes

within California’s largest cities ultimately owe their origins to Chinese

gold-seekers.

The

environmental effects of mining have been the topic of intense study and comment

since the time of the gold rush. Grove Karl

Gilbert (1917) calculated that the industry, especially through hydraulic

mining, had deposited more than 1.6 billion cubic yards of sediment dwarfing

the amount generated by natural processes and other human causes such as

agriculture, grazing, and deforestation.

The channel bottoms of some mountain streams rose several inches per

year. In some cases river channels moved. Vast outwash deposits lay over the Sierra

Nevada piedmont. Towns and agricultural fields

flooded. The bed of San Pablo Bay rose

more than three feet and 9000 acres of tidal mudflat were created around its

edges. Mine sites like Malakoff Diggings

at North Bloomfield became moonscapes as hydraulicking carved away these vast

sediment loads (James 1994; Rohe 1983; USGS 2000).

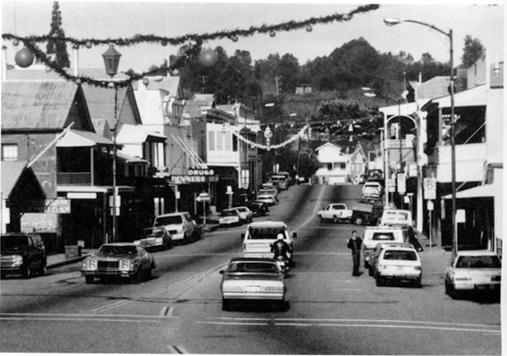

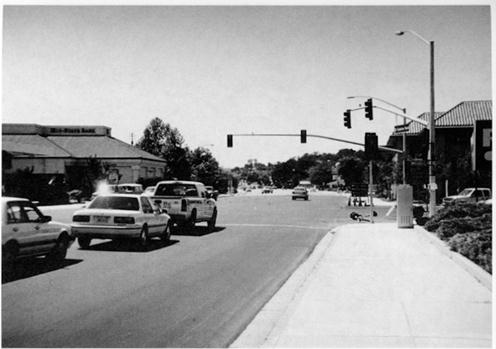

Figure 3: The

historic landscape of the Mother Lode is well represented by the town of Sutter

Creek. Photograph by L. Dilsaver.

Modern

research has shown that erosion and revegetation have ameliorated much but not

all of this amazing landscape disruption.

Rohe (1983) suggests that six feet of debris along the Yuba River is

probably permanent. James (1994) found

terraces formed by mining debris where rivers recut their channels into the raised

beds. He concurs that they are “permanent

over centennial time scales.” All modern

researchers agree that many millions of cubic yards of sediment still line

Central Valley rivers (USGS 2000). Dredging overturned much of that sediment and

left it in parallel rows of man-made eskers.

Dredge spoils cover dozens of square miles along Sacramento River

tributaries. At hydraulic mine sites,

vegetation has reclaimed some cuts and tailings while others remain largely

barren.

Mining

introduced many other environmental impacts, some of which shaped the landscape

in unexpected ways. Dasmann (1999) found

that the mining era wiped out much of the large mammal population, especially

bears. The latter are noteworthy because

they function as ecosystem engineers in their natural habitats moving soil,

uprooting trees and logs, dispersing seeds, and preying on other species (Lawton

and Jones 1995). Mining, like no other

function, impacted the fauna of mountainous areas where many minerals concentrated. At Grass Valley the collapse of shafts and

slopes in the Empire Mine caused surface subsidence noticeable to anyone

driving its streets. Most of the

deforestation that raised the foothills tree line by up to 2000 feet and

decimated the Tahoe area has been reversed. Yet the forest composition has been altered. In semiarid areas chaparral and digger pine

often replaced ponderosa pine (Rohe 1983).

The

gold rush also shaped the politics and culture of the state in ways that show

in the landscape. The rush drastically accelerated

Indian displacement or elimination. The

widely scattered distribution and small size of reservations in California are

byproducts of the geographically expansive search for wealth (White 1998). The international

character of the rush brought large numbers of Chinese to California, resulting

in enclaves of mixed Chinese and American appearance in most major cities.

The

disorganized society of the early mining camps led to social attitudes and laws

that have landscape expression. Batabayal

(1998) suggests that they spawned an “economic liberalism” that decries

government influence in use of public lands.

Later Congress institutionalized this in the Mining Law of 1872 (30 USC

21-54 as amended). Among the effects of

this sweeping law are more than 27,500 extant mining claims on federal land in

California (BLM 1996). The California

Division of Mines and Geology reported 917 active mining operations in the

state during 1995 (Youngs 1996). Individuals

hold most of the remaining claims. As

early as 1944, the Forest Service reported that 21 percent of the claims on its

lands were used for residential or commercial purposes (Friedhoff 1944). The agency now estimates that more than half

the mining claims in the national forests are used for these purposes (Stone

2000). Thus, much of the infrastnrcture

on California’s federal lands owes its existence and distribution to a system

of egalitarian and economically liberal laws devised hurriedly amid the placer

mines of the state.

One

final impact of the gold rush’s legal legacy can affect the landscape in ways

as startling as the hydraulic operations of twelve decades ago. Major corporations use the gratuitous Mining

law of 1872 to open-pit mine for gold. Some

companies confidently plan to pulverize entire hills and retrieve the gold by a

chemical process known as heap leaching.

A landscape left behind by this operation will have its physiography,

soil profile, and biota dramatically altered.

Furthermore, as scientists ponder the significance of the world’s most

acidic water at Iron Mountain near Redding, both the landscape and the health

consequences of mining’s chemical residue remain unknown.

When

California joined the United States in 1850, it became part of the nation’s

public domain and subject to the federal laws governing cadastral surveys. Congress enacted the law of the land, now

known as the United States Public Land Survey or Township and Range System, on May

20th 1785 (Thrower 1966, 4). Sixty-six

years later, on July 17th 1851, a contract surveyor named Leander Ransom

inaugurated the survey in California by establishing an initial point on Mount Diablo

(White 1982, 115). This solitary act initiated

a process that has shaped landscapes throughout the state.

The

Public Land Survey is noteworthy for its geometric organization and grounding

in coordinates of latitude and longitude.

Two sets of lines govern the grid.

A north-south line, or principal meridian, intercepts an east-west parallel,

or base line, at the initial point. Running

parallel to both the base line and principal meridian are lines that form a latticework

of rectangles that are called townships.

Each township incorporates thirty-six square miles and is, in turn,

subdivided into square mile sections. Furthermore,

each section is progressively quartered into smaller and smaller geometric units

(Campbell 1993, 171). Three initial

points, including the original monument at Mount Diablo, were utilized to map

approximately eighty-two million acres, or about four-fifths of the state. The only portions of California not mapped in

this fashion were the colonial ranchos, the Channel Islands, and certain

mineral lands (Uzes 1977, 147-148, 157; White 1982, 117). The main intent of the survey was to exactly

describe and identify land so that it could be readily transferred by the

United States, by the State of California, and by private individuals.

The

Congress of the United States enacted a number of land alienation policies -

the body of laws that govern land transfers - that assisted in the distribution

of the public domain to state and private concerns. Many of these measures, such as the Homestead

Act of 1862, allocated parcels of land concomitant with the quarter sections of

the Township and Range System. Furthermore,

the Land Ordinance of 1785 also contained provisions for the transfer of larger

units such as the full sections granted in considerable numbers to the Southern

Pacific Railroad. However, in an effort

to inhibit the monopolizing of land in large contiguous units, only alternate

sections were initially available for ownership by any individual concern (Johnson

1976, 143). These alienation policies

and their cadastral context are visibly distinguishable on the landscape today.

In

the San Joaquin Valley, for example, the moister eastern regions were settled

relatively early during the 1850s and 1860s as the public domain was transferred

to homesteaders through a variety of alienation acts (Eigenheer 1976, 275-284).

Although these initial land ownerships

were relatively small, the cadastral framework assured that farmsteads were

spatially scattered and isolated from those of neighboring landholders (Jordan-Bychkov

1999, 79). On the other hand, where

alternate railroad sections were present in the Central Valley, these lands were

initially unavailable or avoided by early immigrants. Later, in the 1870s and 1880s when the rail

road owners began selling off the sections that had been previously granted to

them, landholders from adjoining sections or newcomers to the region began purchasing

the available land in larger units. This

explains why in some rural areas of California east of the coast range there are

fewer farmsteads and associated settlement forms visible in sections once owned

by the railroad (Preston 1981, 109).

Visual

contrasts between alternate sections of townships are apparent in a number of

other locations in California. A case in

point is the pattern of planned housing developments in the Mojave Desert. Contrasting landscapes between alternate

sections are distinctly revealed in the vicinity of California City where

subdivided sections containing roads and houses are interspersed among sections

of desert. Similarly, oil drilling and

pumping in western Fresno and Kings counties began on

alternate sections during the first decades of the twentieth century. Since then, oil development has spread in

some areas to adjoining sections, but the checkerboard contrasts between the

landscapes of oil and ranch or farm land still exist (Jennings 1953).

The

Public Land Survey has contributed both directly and indirectly to the

contrasting landscapes between certain regions of the Great Central Valley. In

contrast to the east side, a much greater portion of the land on the west side

of the valley was monopolized during the 1860s and 1870s. Owing to the inaccurate environmental assessments

of the original surveyors, the availability of land, and the fraudulent use of

alienation policies such as the Swamp and Overflowed Lands Acts and Military

Scrip, the public domain on the west side was acquired by relative few

claimants (Eigenheer 1976, 312-320). Land

speculation was often the motive for these endeavors, and resulted in the

removal of huge portions of the public domain.

Most notorious among the monopolists was Henry Miller whose acquisitions

included a one hundred mile stretch of land along the San Joaquin River

(Robinson 1979, 192-193). The

contemporary legacy of his and other land monopolies during the nineteenth

century is readily visible in the extensive corporate landscapes that contain

larger fields and fewer homesteads than the rural landscapes on the eastern

side of the valley (Preston 1981, 111-112).

An indirect consequence of this division is that settlements on the west

side of the valley such as Mendota and Corcoran tend to be more impoverished

than those in the east as fewer landowners contribute less to the local economy. The corporate settings on the west side are

largely responsible for these economic and settlement disparities and the

visible landscapes of poverty bear testimony to the linkage between the Public

Land Survey and community health (Goldschmidt 1978).

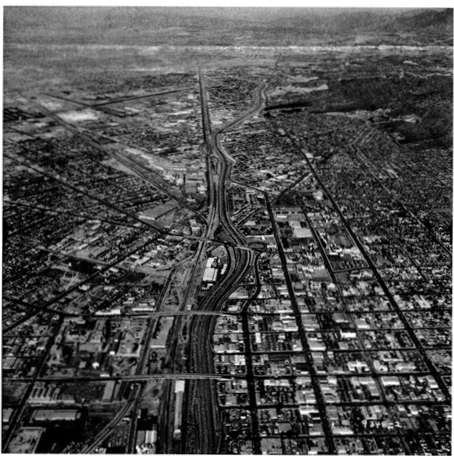

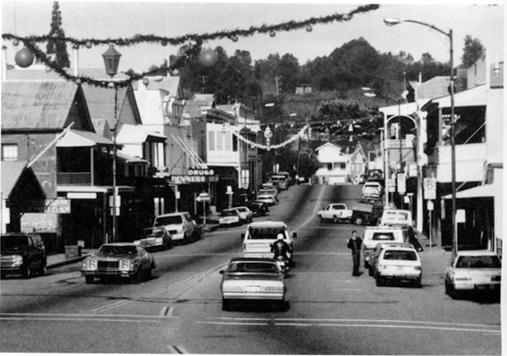

Perhaps

the most striking contemporary legacy of the Public Land Survey is the visible

geometry of rural California (figure 4).

In the flatlands it imparted rectangularity to the landscape that is

visually inescapable. Public jurisdictional

boundaries (e.g., parks, forests, military bases, national monuments, wildlife reserves), property lines, homesteads, fences,

roads, canals, field and orchard patterns, and even a few water bodies dearly

demarcate the cardinal orientation and checkerboard fabric of the cadastral

system. The settlement infrastructure

conforms particularly well to sectional boundaries, its rectangularity

intensified through subsequent farm fragmentation and consolidation. In more densely populated areas, section

lines serve as the framework for continuing subdivision.

County

roads in the Central Valley, for example, usually conform to sectional and township

boundaries. Many straight north-south roads

make an abrupt right angle jog where they encounter the survey correction lines

that occur every twenty-four miles north and south of a base line (Greenhood

1971, 25). Even interregional roads such

as Highway 99 and Interstate 5 in the northern San Joaquin Valley are congruent

over extensive stretches with the adjoining sectional or township boundaries

(Johnson 1976, 143; Johnson 1990, 137-141).

The

impact of the Public Land Survey is equally impressive among urban landscapes

where variations on the rectangular grid pattern sometimes occur. A number of

settlements established by the railroad exhibit a rectangular street framework

oriented to the tracks rather than to the cardinal directions inherent in the

survey. However, once successful railroad towns expanded into the countryside,

developers commonly broke from the original cadastral orientation established

by the railroad and built in accordance with the Public Land Survey. The street

patterns of Modesto and Fresno, like those in most railroad towns, display this

phenomenon.

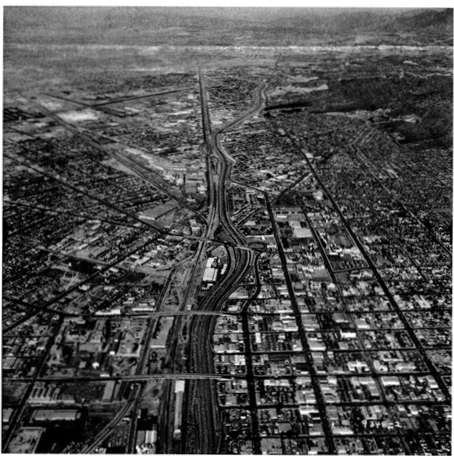

Figure 4. Figure 4. The

familiar checkerboard pattern of the Township & Range land division system

is especially pronounced in flat areas such as the San Joaquin Valley near

Kettleman City. Photograph provided by

the California Department of Transportation.

In

towns and cities that have strictly adhered to the geometric dictates of the

Township and Range System, its influence extends to all aspects of the human

landscape. Even the smallest features

such as town lots and the organizational geography of homes, yards.fences, and

driveways in these communities are oriented to the straight lines of the survey

system. Its impact is evident, as well around

the expanding margins of California’s burgeoning cities. Cities grow at the.expense

of open countryside and in the process adopt the configuration of pre-existing

cadastral patterns. In this fashion,

urban boundaries spread along the edges of sectional roads before filling in

the development tracts (Jordan 1982, 54). Moreover, land incorporated for urban

expansion is usually acquired in rectangular units of varying sizes that is, in

turn, a legacy of the survey’s influence on ownership patterns. As a result, the distinction between new urban

developments and the rural hinterland is often stark and delineated in

conformance with the cardinal directions. The zones of suburban growth around downtown

San Bernardino and Sacramento, for example, are distinct for their miles of rectangular

blocks and uniform streets.

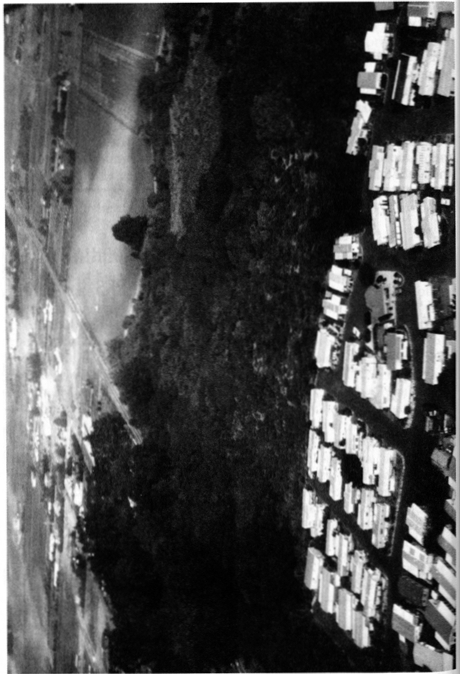

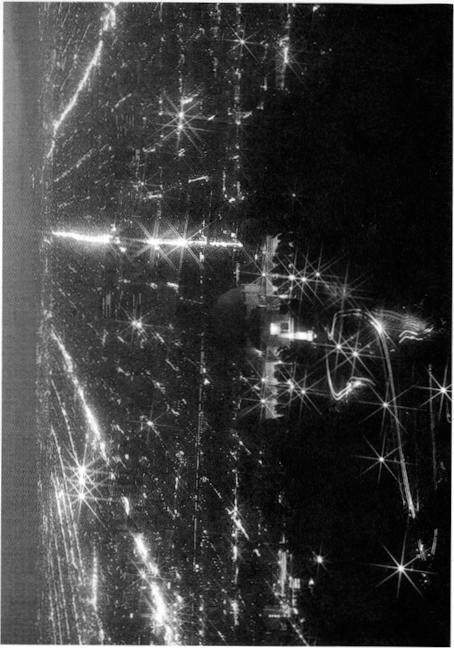

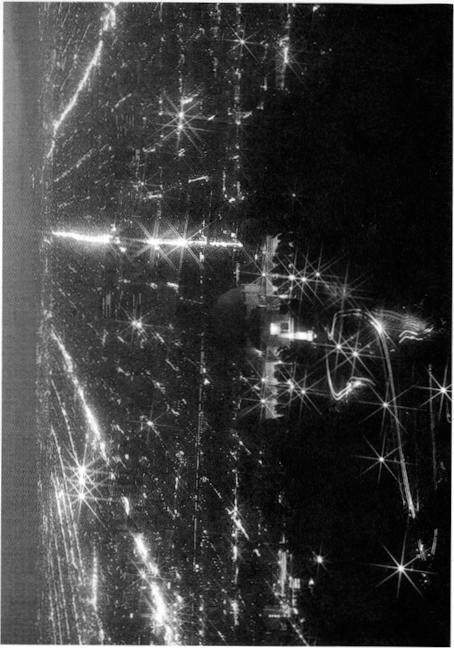

After

dark, the rectangtangularity of urban lights is one of the most prominent and

singularly striking patterns of California’s nightscape. This nocturnal panorama is especially impressive

from an elevated perspective offered by highlands or aircraft. Indeed, the westward descent into Los Angeles

International Airport at night provides unsurpassed visual testimony to the

sinews of the Public Land Survey.

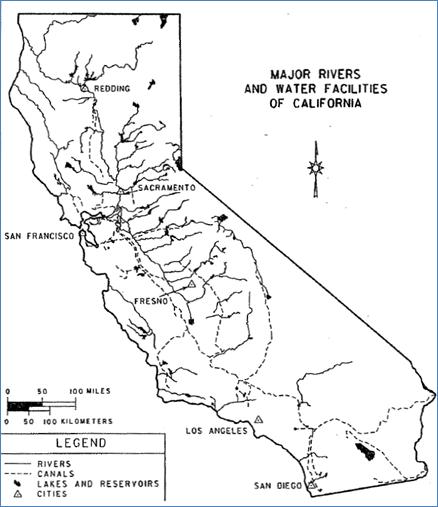

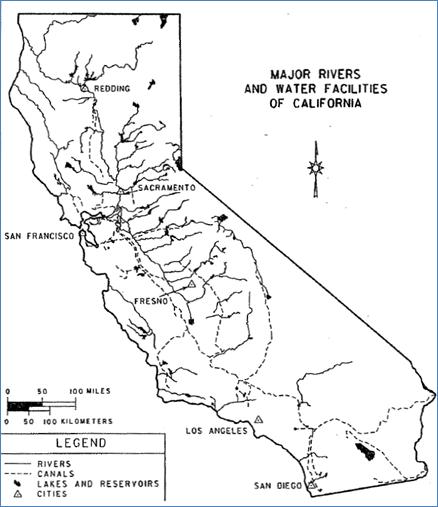

Figure 5:

The major federal, state, and local water transfer structures in

California. Source: California

Department of Water Resources.

Cartography by Margarita K. Pindak

Figure 5:

The major federal, state, and local water transfer structures in

California. Source: California

Department of Water Resources.

Cartography by Margarita K. Pindak

During

the early years of the gold rush, San Francisco grew so rapidly that by 1852 it

had outgrown its own local supplies of fresh water. In that year the city

approved a petition to tap a source of permanent water from another drainage

system. After several delays and changes

to the original plans, in 1858 water was transported by flume from Lobos Creek

five miles to the mains of downtown San Francisco (Delgado 1982, 31-35). On completion of the project, San Francisco became

the first major municipality in California to receive a pennanent water supply

from another watershed. The tapping of Lobos

Creek provided the precedent that inspired subsequent efforts to acquire more distant

and widespread sources of fresh water by San Francisco and other urban areas throughout

California (Figure 5). California’s exceptional

urban growth may be traced to it and few events have initiated processes more

importan to the shaping of the state’s contemporary landscapes.

The

Lobos Creek diversion and subsequent projects allowed San Francisco to increase

from a pre-gold rush population of 300 in 1846 to 80,000 by 1862. Additional water was again required, and the

cit y expanded its infrastructure to impound and import more water. First from the peninsula to

the south and then from the southern East Bay (Leonard 1978, 38-39, 42-43).

By 1900, the city had reached a

population of 340,000 and was now looking to the Sierra Nevada, and

specifically the Tuolumne River, for additional sources (Hundley 1992, 120,

169-170). The lynch pin of the Tuolumne

system would be the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park

(Kahrl 1978, 29-31; Brechin 1999, 71-117). After considerable controversy, San Francisco

was victorious and by the early 1930s was importing most of its municipal requirements

from the Tuolumne watershed through the 148 mile long Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct. For years following the initiation of the

project the system continued to be upgraded with a spectacular array of

tunnels, dams, pipelines, inverted siphons, and powerhouses.

Imported

water provided San Francisco with the ability to modify national parks,

national forests, cities, and farmlands.

Reservoirs such as Hetch Hetchy, Crystal Springs, Don Pedro, and Calaveras

cover hundreds of square miles, and the intervening landscapes are laced with

pipelines, powerhouses, and transmission lines.

Many of these facilities and their rights-of-way boast a variety of recreational

functions including camping, hiking, boating, and fishing (Benchmark Maps 1998,

14-17). These attractions, in turn, have

generated an array of business and administrative landscapes along access

routes and within gateway communities. San

Francisco’s jurisdictional authority to dictate land use and management practices

around the project’s facilities is extensive.

The city has considerable land and water rights in a number of peninsula

and southern East Bay counties and county, state, and federal fiats guarantee its

influence over other lands. One result

of this control is maintenance of open space by the city in some Bay Area

suburbs (Brechin 1999, 88; Leonard 1978, 24-25).

Although

Tuolumne water temporarily renewed San Francisco’s urban growth, further

expansion was eventually curtailed more by political and physical constraints

than by a lack of water. Nevertheless,

the city’s influence is still felt in its ability to control water resources

and as a precedent for other metropolitan environments. San Francisco currently possesses substantial

water and power surpluses and it sells the excess to nurture continued urban

expansion in more than fifty neighboring communities. Virtually all of San Mateo County’s

residents, for example, depend upon water sold to them by San Francisco (Leonard

1978, 25; Selby 2000, 194). Additionally,

the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) mimicked San Francisco’s urban

water system and imported Sierra water from the Mokelumne watershed. This water in turn continues to fuel urban

expansion in the vicinities of Walnut Creek, Concord, and Danville and the

growth has inspired EBMUD to consider other distant sources such as the Feather

River (Littleworth and Garner 1995, 9-10).

The

urban water system in Southern California conforms to the overall pattern of San

Francisco’s diversion of the Tuolumne and the East Bay’s diversion of the

Mokelumne River; however, the impact is of a greater magnitude. Control of the watershed of the Los Angeles

River had sustained Los Angeles in its youth.

However, by the end of the nineteenth century, Los Angeles had nearly

exhausted its ability to extract more water (Gumprecht 1999, 41-81, 85-129). To sustain growth and prosperity, the city

tapped the streams and ground water from the Owens and Mono Basins far to the

north by constructing the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

This storage and conveyance system is half again as long and delivers nearly six times as much water as San Francisco’s Hetch Hetchy

project. The landscape impacts in the

areas of extraction and consumption are far greater as well (Kahrl et al. 1978,

51).

The

aqueduct allowed the population of Los Angeles to increase twelve fold and expand

in area ten fold between 1900 and 1950 (Kahrl 1976, 115). Like their counterparts in Northern

California, the storage and conveyance facilities have spawned bountiful

recreational and commercial landscapes (Benmmark Maps 1998, 19, 25, 25). However, the consequences of urban water

extraction have inflicted unparalleled changes on preaqueduct environments. Due to the Los Angeles diversion, Owens Lake

is completely drained and Mono Lake severely depleted. The exposed lakebeds and shorelines are

disconcertingly dramatic, and the sky over the southern Owens Valley is now

turbid with dust. Moreover, the

modification and elimination of riparian vegetation in the Owens Valley and along

the former courses of Mono Basin’s diverted streams are notable byproducts of

the aqueduct system (Gaines and DeDecker 1982; Reisner 1993, 101). The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power

(DWP) exercises jurisdiction over 300,000 acres of land in Owens Valley and

continues to curtail urban expansion around settlements such as Bishop and condone

the deliberate removal of numerous rural farmsteads. Furthermore, the fields of irrigated crops

that once carpeted the valley have been rendered into scrublands and pasture

(Hart 1996).

Unbridled

urban expansion in Los Angeles and other cities in southern California

immediately prior to and following World War II created the need to import

additional water from the north by the California Aqueduct and from the east by

the Colorado River Aqueduct. Although

the majority of the water is utilized for irrigation elsewhere, the Colorado

River serves water to over fourteen million people inhabiting 500 cities spread

over 5000 square miles (Selby 2000, 199).

As a consequence of this fresh abundance of imported water, Los Angeles

doubled its population again between 1940 and 1970 (Kahrl et al. 1978, 42). Furthermore, its neighboring cities

stretching from Ventura to San Diego have expanded even faster, sustaining rapid

growth into the twenty-first century.

Many

settlements in California require varying amounts of fresh water from

subterranean sources. However,

interbasin water transfers have supported most of the state’s urban expansion

and sustained a booming economy. Indeed,

cities over large areas of the state have benefited from water projects that were

constructed primarily for agricultural purposes such as the Central Valley

Project. Since San Francisco’s fateful

diversion of Lobos Creek in September 1858, California cities have contributed heavily

to the construction of over 1300 dams and associated facilities currently

scattered throughout the state (Selby 2000, 194, 203, 209). This reciprocal relationship between cities

and water is a driving force behind the state’s continuing population explosion

and the expansion of its urban landscapes.

Most

of California’s 54 million people live in suburbs, and the resulting landscapes

have fundamentally refashioned the visible scene. The state’s most extensive suburban

landscapes ring Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego where the vast

majority (70-80 percent) of the urban population lives beyond the boundaries of

the central city (Kenworthy and Laube 1999).

Similar sprawling collections of dispersed housing, two-car garages,

backyard patios, commercial strips, and shopping malls can also be found from

El Centro to Redding. Much of today’s

suburban landscape has been created since 1950, although the roots of

California’s suburbs extend well back into the nineteenth century. The penchant for escaping central cities was

already apparent in the vicinity of New York City as early as 1810 (Brooklyn

Heights) Jackson 1985, 25-50). In

California, the 1864 completion of a rail line from San Francisco to San Jose

spawned the first generation of suburbs (Burns 1977, 1980). Bay Area elite were attracted to the pastoral

lifestyles and low density housing of planned suburbs such as Burlingame and

Atherton. It was the beginning of a

landscape-shaping process that continues unabated almost 150 years later.

California’s

suburbs have enduringly altered earlier landscapes. Where suburbs have sprouted in valley

settings, they have often consumed huge tracts of agricultural land. Indeed, over 25 percent of the state’s best soils

are now covered by urban or suburban land uses.

For example, Los Angeles County lost over 45,000 acres of citrus land to

suburban growth in the ten years following World War II (Nelson 1959, 80;

Banham 1971, 161-77). As suburbs

multiply, suburbanites bring in thousands of exotic trees, plant extensive

lawns, displace native animals with their suburban pets, and forever alter the fundamental

ecological setting (Price 1959; Streatfield 1977). Foothill environments, including many around the

Bay Area as well as inland Southern California, have also been dramatically

altered by suburban growth (Banham 1971, 95-109). Natural vegetation has been encroached upon,

and drainage and topography have been reconfigured to suit the needs of the California

hill-dweller. Frequently, such settings

are also the scene for fire and flood damage, a reminder that the natural landscape

is not infinitely malleable to meet human needs.

Why

are suburbs where they are on the California landscape? Dozens of suburbs owe their origins to the

geography of nineteenth-century interurban rail lines that radiated from major

cities such as San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Indeed, southern California boasted over 1100 miles of rail network and these

links encouraged suburban growth in places such as the San Fernando Valley, Pomona,

and Anaheim (Bottles 1987). Other

suburbs popped up near industrial activity that sprouted beyond the boundaries of

traditional cities (Hise 1997; Matthews 1999; Viehe 1981). For example, Brea and Fullerton appeared near

oil fields, Burbank grew in response to the movie and aerospace businesses, and

San Jose benefited greatly from high-technology industries in Silicon Valley. Real estate promoters have also shaped the growth

of the suburban landscape. Southern

California’s real estate boom of the late 1880s produced more than 60 new

suburbs. While some vanished,

communities such as Glendale, Monrovia, and Redondo Beach owe their origins to

such activity (Nelson 1959; Streatfield 1977a).

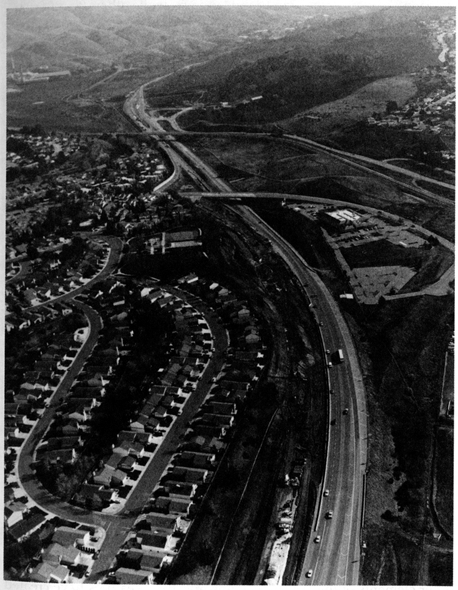

Throughout the state, however, the automobile and its associated road

network have undoubtedly exercised the greatest influence on the location and

spatial extent of California’s suburban landscape (Foster 1975; Meinig 1979). Between 1920 and 1950, the automobile’s

flexibility encouraged the infilling of open space between older discrete,

suburban communities on the edge of major cities. Since 1950, powered by spreading freeway

construction, the automobile has enabled much more suburban growth often 40 to

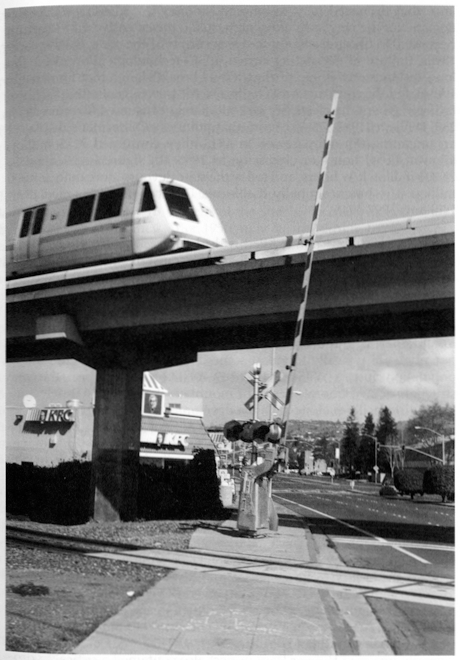

60 miles or more from the central city (figure 6). Today, Tracy and Manteca have become Bay Area

suburbs, while Temecula and Moreno Valley are within the ever-spreading reach

of Los Angeles (Mcintire 1998, 44-49).

A surprising variety of settlement

patterns and street layouts are associ ated with California’s suburban

landscape (Palen 1995). The curving

streets, abundant foliage, and large lots of the state’s elite suburbs form one

enduring settlement model (Burns 1980; Jackson 1985, 178-81; Streatfield 1977b). Boasting social and spatial exclusivity as

well as an abundance of environmental amenities, settings such as Hillsborough

(near San Francisco), Montecito (Santa Barbara), and Beverly Hills (Los Angeles)

illustrate the pattern. Indeed, Palos

Verdes, a seaside elite suburb near Los Angeles was the carefully planned brainchild

of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.

Another common suburban settlement pattern is the repetitive grid of

cardinally oriented streets, rectangular lots, and mass-produced single-family

housing. This distinctive settlement

pattern expanded greatly after World War II as pent up demand for housing, a

new scale of real estate and building promotion, and an accommodating federal

government (FHA loans and the GI Bill spurred home construction.

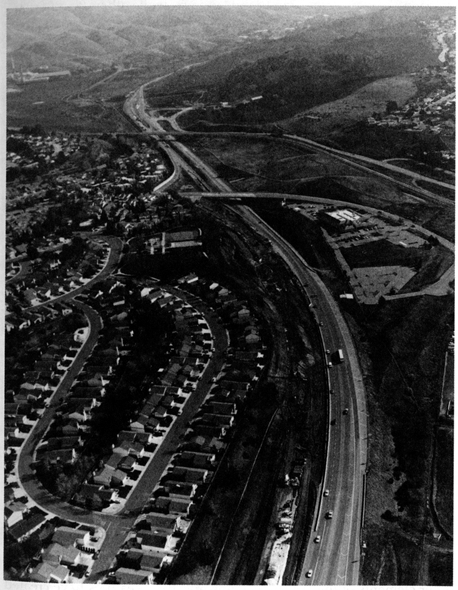

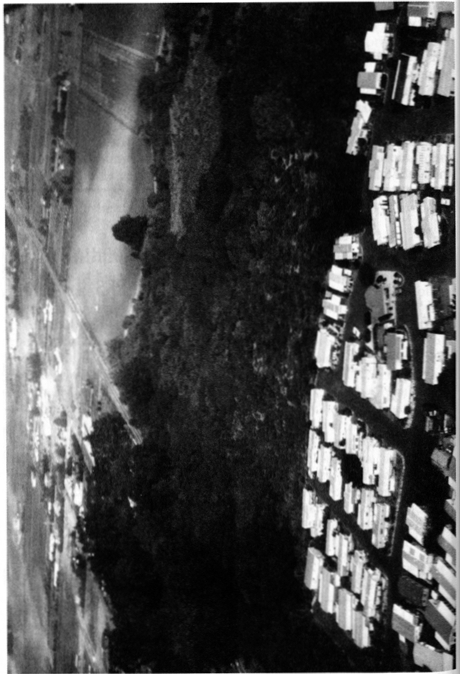

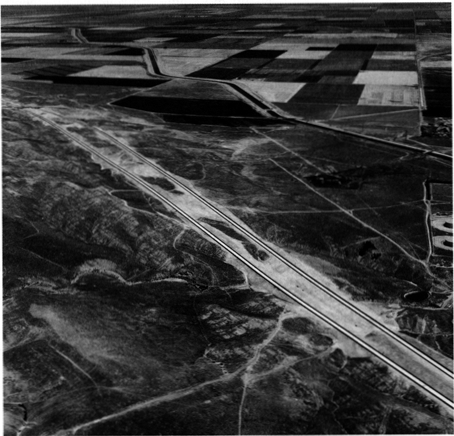

Figure 6. Figure 6. Suburban sprawl clinging to Interstate 680 in Contra Costa County.

The

1950s and 1960s witnessed large development projects in such localities as

Lakewood Village south of Los Angeles and Daly City and Foster City near San

Francisco (Banham 1971; Burns 1977; Price 1959). Many of California’s suburbs, however, have

sprouted since 1970, and these developments have featured more eclectic

settlement patterns. Some have been

shaped by large-scale coordinated planning (Mission Viejo) of street layouts

and land use, while others (San Bernardino and San Jose) offer a varied,

spatially extensive collection of street plans and population densities, often

depending on income levels, local topography, and the tastes of developers

(Abbott 1993, 123-48; Kling, Olin, and Poster 1991) (Figure 7). Some feature the familiar grid, but many

subdivisions also offer curvilinear layouts, cul de sacs, and a greater mix of

single and multiple-family units.

Suburban

architecture is similarly varied. Residential

districts reflect different preferred building styles, depending on income and age

of home construction (Abbott 1993, 123-48; Banham 1971; Meinig 1979; Rubin 1977). Bungalow-style housing, for example,

signifies a neighborhood usually created between 1900 and 1925. Single-story ranch-style housing tracts

multiplied in the 1950s and 1960s, covering many additional square miles of the

California landscape. Elsewhere, higher density

suburbs suggest that rising land costs and changing lifestyles of the past

thirty years have created more demand for apartment, condominium, and townhouse

living.

Added

to this increasingly diverse accumulation of residential architecture are the

varied commercial, retailing, and industrial landscapes that shape the suburban

scene today (Banham 1971; Bottles 1987; Preston 1971; Longstreth 1997). Commercial strips and suburban shopping malls

create a landscape that is mass-produced, franchised, and packaged to meet every

need of the California consumer. Newer

suburban complexes, such as those in Orange County and Silicon Valley, also

offer an ever-growing variety of land uses that is creating a new landscape

some have even described as “postsuburban”.

·Perhaps signaling a common American future, these places are

characterized by multiple regional scale shopping malls, entertainment

complexes, a mix of office parks and space-extensive industrial facilities

(often oriented to the global information economy), a bewildering network of

freeways and multilane surface streets, and a residential landscape, with both single

and multiple-family housing, oriented around convenience, consumption, and personal

privacy (Kling. Olin,

and Poster 1991). As with so many other

elements of the California landscape, these features have created a visible

scene already being widely replicated far beyond the bounds of the Golden State.

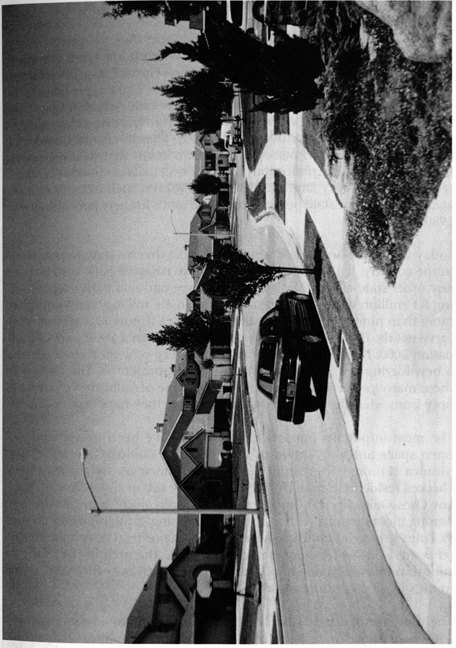

Figure 7. Figure 7. The

expansive and repetitive landscape of the California suburb is exemplified by

this tract in Lemoore.

In

1864, the literate American public felt disgust over the privatization and

tawdry development at Niagara Falls. When

it appeared the same would befall Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove,

Congress set them apart as a public park for California (13 Stat. 325). Eight years later, lacking a state to receive

land, another Congress established Yellowstone National Park. Yosemite, however, was the groundbreaker, the

nation’s first state and, in reality, national park. A year after its creation, Frederick Law

Olmsted laid out a management prescription that would become the blueprint and

the philosophy for park systems nationwide (Olmsted 1865). A half-century later the Yosemite grant returned

to federal management while the state pursued redwood lands for new parks

(Engbeck 1980).

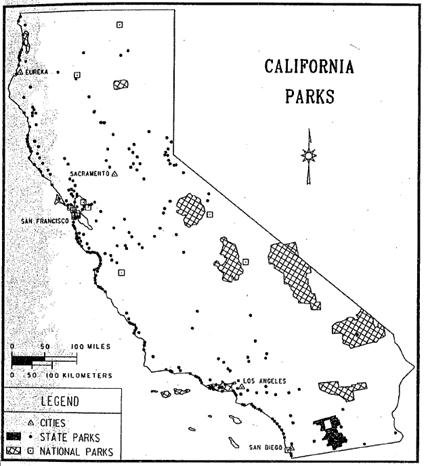

Today

California boasts the largest and most diverse state park system in the country. It also has more units of the national park

system than any other state except Alaska.

Twenty-three national park units, totalling 8.1 million acres and 265

state parks at 1.4 million acres comprise more than nine percent of the state’s

land area (figure 8). Together they serve

nearly 120 million visitors per year (California State parks Foundation 2000;

National Park Service 1997). Every

ecological division and a bewildering array of historic themes are

represented. The impact of these many

preserved places on the landscape of California results not only from what they

have wrought but what they have stopped.

The

most important impacts of the parks have been preservation of open space and

prevention of development Golden Gate and Santa Monica National Recreation

Areas and numerous state parks have checked residential sprawl in the state’s

major urban zones. Torrey Pines, Los

Osos Oaks, Crystal Cove, Topanga Canyon, and Mount Diablo are among the state

units with subdivisions lapping at their borders (Figure 9). Point Reyes National Seashore halted a major

tract development after roads and twelve houses had been built. The area of the planned suburb now sweeps

down to Limantour Spit with only three employee houses in view (Duddleson 1971;

Pozzi 2000).

The

presence of a park also has blocked other types of development. After San Francisco builthetch Hetchy Dam in

Yosemite, Congress, in 1921, enacted an amendment to the Federal Power Act

forbidding its implementation in national parks (41 Stat. 1353). In the case of the Kings River, Congress

blocked a Los Angeles reclamation project by adding the area to Kings Canyon

National Park. The Nationa l Park

Service (NPS) and park supporters also blocked several trans-Sierra road

projects, losing only at Tioga Pass. An

ambitious plan to build a high elevation road

along the entire Sierra Nevada also

failed due to NPS opposition (Dilsaver and Tweed 1990, 182-186).

Arguably the most important open space

preserved by the parks is along California’s crowded coast. The California state park system holds title

to 280 miles, or 25 percent of the shoreline.

National parks account for nearly 100 miles more, not including the

Channel Islands. Although all open space

is important, more than a fourth of California’s parklands are designated wilderness. Here the controls on construction and use of

mechanical transport promote a more complete natural signature on the land

(Schaub 2000).

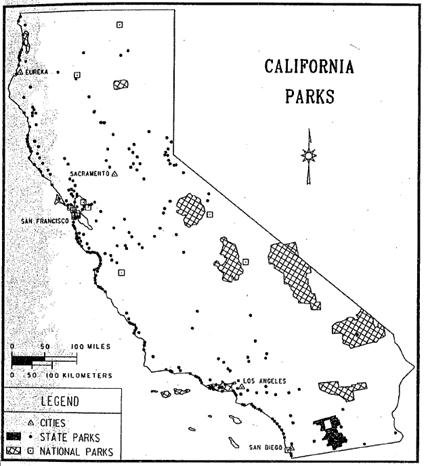

Figure 8Figure 8. National and state parklands in Califonia. Sources: California State Parks and National

Park Service. Cartography by Margarita

M. Pindak

Figure 9. Los

Osos Oaks State Park near San Luis Obispo protects an island of nature amid

residential and agricultural development.

Photograph provided by the Photographic Archives of Catifomia State

Parks

Despite

the preservation of open space, the legacy of human activity is present in all

288 park units. Park management has actively

altered ecosystems while at the same time causing them to diverge markedly from

the lands surrounding them. Among park

managers’ early steps were, first, enjoinment of lumbering, hunting, and most

grazing and, second, suppression of fire.

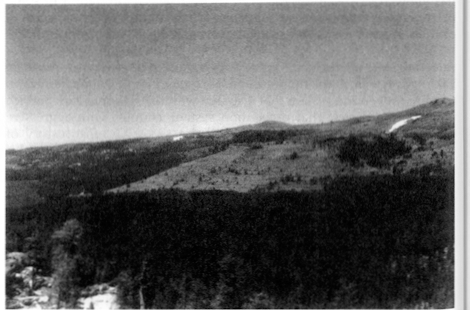

Parks contain many areas of old-growth forest coveted by loggers. Originally, California boasted nearly two

million acres of redwood groves. Only

86,000 acres remain, 93 percent of them in parks and reserves (Redwood National

Park 2000).

Rangers

practiced extensive fire suppression prior to the mid-1960s. During that time forest composition altered,

sometimes dramatically, especially in the mountains. For example, giant sequoias simply did not

regenerate for nearly a century. In the process,

species like white fir expanded in both range and density of coverage among the

sequoia groves (Sequoia and Kings Canyon 1987).

During that time the fuel load in forests built up to an unnatural level

that has rendered prescription burning a feeble corrective device.

Park

management of fauna has also impacted the landscape. Early efforts to eliminate predators, coupled

with bans on hunting, led to eruptions in ungulate populations. Deer in particular wreaked a devastating

impact on vegetation. The chain reaction

of these ecological changes rippled through communities contributing to near

elimination of some species and increases in others. Subsequent efforts to protect predators, especially

black bear and mountain lions, have led to the further divergence of parkland

ecology from the surrounding areas. Bears,

the aforementioned ecosystem engineers, are densest in the large parks where

hunting is forbidden.

Another

impact of the national and state parks is in preservation of historic structures

and landscapes. Indian settlement sites,

Spanish missions, forts of various groups, and agricultural industrial,

commercial, and even Hollywood landscapes are preserved. Many ethnic landscapes have persisted due to

their inclusion in park zones or to financial support from the state or

national parks. The preservation

movement, begun at Yosemite, led to the 1906 Antiquities Act (34 Stat. 225) for

protection of historic resources. Ironically,

President Clinton recently used it to protect the offshore rocks and islands

along California’s entire coastline (US Department of Interior 2000).

Within

the parks’ auto-accessible zones, planners design buildings and landscapes to

exacting specifications and styles. This

“parkitecture” is duplicated throughout both systems as well as various

regional and local parks. Planners

design campgrounds, buildings, parking areas, and

the disguised infrastructure to

support them to have a “rustic” look that is both carefully wrought and itself

historic (Carr 1998). Still another

influence of the parks extends beyond their boundaries. Most national and state parks are major

recreation destinations. The road system

has evolved to cope with traffic coming to internationally significant sites

like Yosemite and Sequoia, as well as the many accessible beach parks. Gateway towns such as El Portal, Mariposa,

Three Rivers, and Borrego Springs have their own landscapes of

tourism-lodgings, dining establishments, souvenir shops, and a remarkable array

of loosely associated amusements. Parks

in urban zones, with their protected open space, increase the value of adjacent

lands. This, in turn, often leads to

more expensive residential and commercial development. Also, parks and their tourism provide

economic multiplier effects that spawn additional development in surrounding

regions.

Finally,

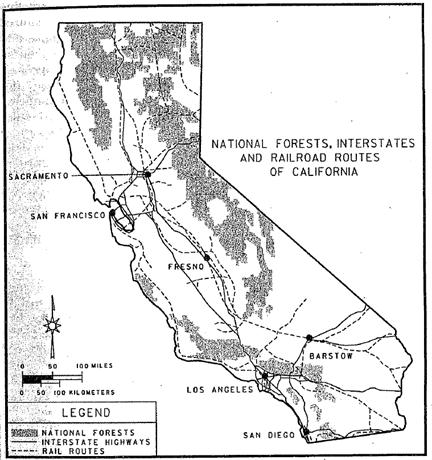

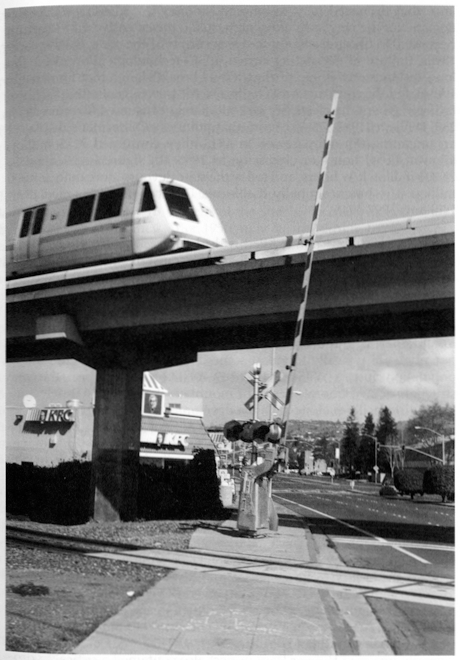

among the subtlest influences of the national and state parks is their