Beowulf Group Web Project

Beowulf: The Sapiential and Normative Functions of the Poem

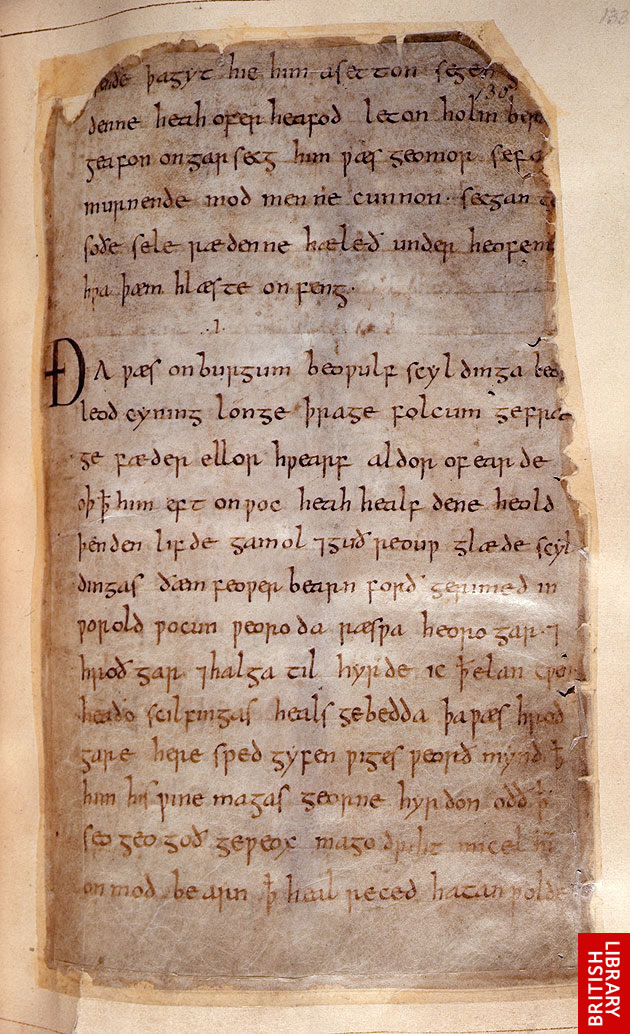

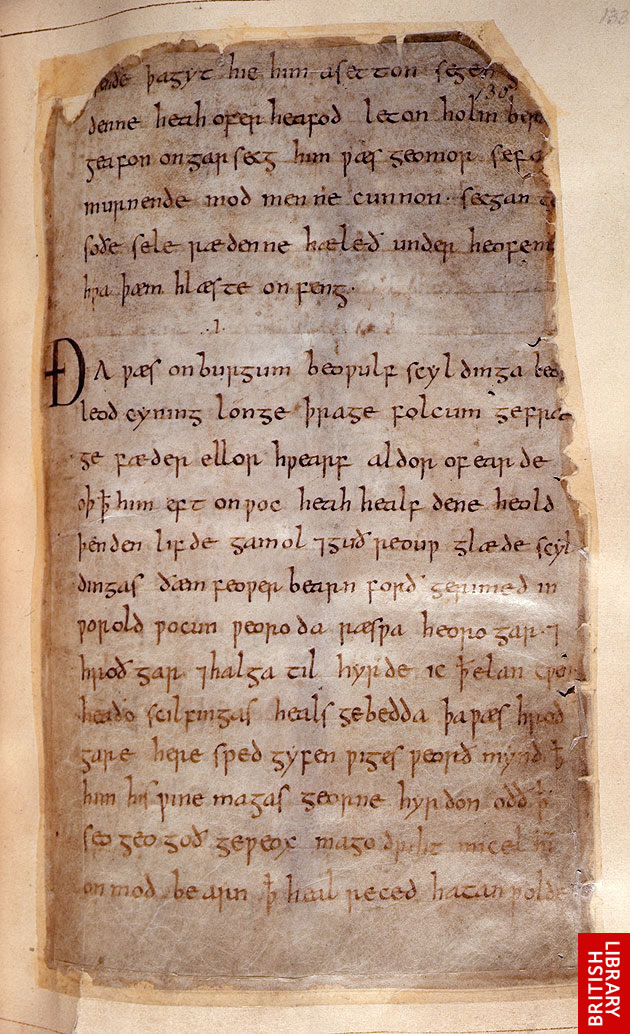

A page from the sole surviving manuscript containing the Beowulf poem, which is currently located at the British Library. This image was obtained from the Online Gallery of English Literature of the British Library. The proper citation for the manuscript is London British Library Cotton MS Vitellius A. XV.

ohn D. Niles, in his article, "Reconceiving Beowulf: Poetry as Social Praxis", presents an interesting framework in which to evaluate and analyze the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf based upon six traditional functions of literature: the ludic, the sapiential, the normative, the constitutive, the socially cohesive, and the adaptive (148). Niles asserts that oral poetry "constitute[s] a praxis affecting the way people think and act", thereby providing "a site where things happen, where power is declared or invoked, [and] where issues of importance in society are defined and contested" (143). Of particular interest in this portion of the group project, are the sapiential and normative functions of Beowulf; what wisdom and values did the poem provide to its intended audience.

n a period when books "served as tools of social order and manifestations of authority, many people could look favorably on a book that legitimized Anglo-Saxon institutions of kingship and thaneship, confirmed Christian ideals of sacrifice, and promoted a common culture among the English and the Danes, all through a fabulous tale set in the heroic North" (Understanding Beowulf 146-47). As Beowulf would have functioned to impart wisdom/knowledge (the sapiential) and social values (the normative) to its intended reader, one must contemplate who was the intended reader of the manuscript to fully understand the wisdom and values presented. In "Understanding Beowulf: Oral Poetry Acts", Niles asserts that most scholars believe that the readership of the manuscript was directed to "either a monastery with lax discipline or one with a special connection to the secular nobility"; especially as King Alfred's educational reforms produced a literate secular nobility (147). Moreover, as schools were primarily for the ecclesiastical class, poetry, such as Beowulf, served an important educative role for the secular aristocracy (Reconceiving Beowulf 151). Thus, for purposes of this analysis, it is a reasonable presumption that the intended readership of the poem was the secular (or lay) nobility, and the morals and values contained within would apply to them.

ines 3077-3086 of Beowulf help to illustrate how the sapiential and normative aspects of the poem functioned. In these lines, Wiglaf, addressing the Geats, states:

"Oft sceall eorl monig ānes willan

wræc ādrēog[an], swā ūs geworden is.

Ne meahton wē gelæran lēofne þēoden,

rīces hyrde ræd ænigne,

pæt hē ne grētte gold-weard þone,

lēte hyne licgean þær hē longe wæs,

wīcum wunian oð woruld-ende;

hēold on hēah-gesceap. Hord ys gescēawod,

grimme gegongen; wæs pæt gifeðe tð swīð,

þe ðone [þēod-cyning] þyder ontyhte. (3077-3086)

Howell D. Chickering, Jr.'s translation reads:

"Often many earls must suffer misery

through the will of one, as we do now.

We could not persuade our beloved leader,

our kingdom's shepherd, by any counsel,

not to attack that gold-keeper,

to let him lie where long he had lain,

dwelling in his cave till the end of the world.

He held to his fate. The hoard has been opened

at terrible cost. That fate was too strong

that drew [the king of our people] toward it.

As Wiglaf refers to Beowulf as their "beloved leader" (Beowulf 3079), the reader would reflect upon the positive attributes we have learned of Beowulf throughout the poem. For example, one would remember Beowulf's ability to keep peace within the kingdom and not seek treacherous quarrels, his lack of avarice demonstrated by his generosity as a ring-giver, and his early heroism within Hrothgar's hall. His virtues which are extolled throughout the poem, become even more apparent when compared to the actions of characters such as Heremond, who led his people into needless warfare and sorrow (901-06), and Modthrytho, whose actions were not queenly (1931-43). Thus, "the poet invites his audience to emulate the positive example" of Beowulf and "scorn the negative examples of the others (Reconceiving Beowulf 153).

dditionally, Beowulf offered "Anglo-Saxon aristocrats memorable profiles in courage" as well as an understanding of "the need for generosity, moderation, and restraint on the part of the rulers" (152). The poem defines "through concrete example and counterexample" concepts and "qualities that hold a society together" (152). These social values are unequivocally stated. The poem presents "virtue as acts that sustain and vice as acts that disrupt human brotherhood" (Kroll 117). Beowulf demonstrates "an exemplary sense of responsibility for other men" (129); one which should be emulated. In fact, Wiglaf acknowledges and accepts this social imperative when he "willingly faces his own death in order to carry out his responsibility as Beowulf's brother" and kinsmen (128).

et, Beowulf is not perfect, as a human he is flawed. When Wiglaf opines, "[o]ften many earls must suffer misery through the will of one" (Beowulf 3077-78) we are reminded of Beowulf's past boastfulness and eagerness to be recognized for his heroic deeds. In fact, Hrothgar warns "Beowulf against pride, anger and selfishness that lead to the destruction of human community" (Kroll 120). Moreover, Hrothgar, unlike Beowulf, recognized the limitations of his advanced age and chose not to fight Grendel because he had a responsibility to his kingdom. Thus, one can argue that Beowulf, to the detriment of his people, succumbed to his pride and need for glory in choosing to fight the dragon. Certainly, his desire to prove that he was still able to defeat the dragon (as he had Grendel and his mother) could have led to his imprudent decision to engage in battle. Regardless, of the end result, Wiglaf still admires and loves his lord, concluding he was good king.

aken in this context, not only would Beowulf serve as an exemplar on how one should behave with both courage and honor, but also as a cautionary tale, instructing that sometimes personal heroics need to be subsumed for the good of the kingdom. Despite his fate in the poem, Beowulf still serves as a positive role model, especially when contrasted against "the characters who figure as foils" to him (Reconceiving Beowulf, 153). In the end, Beowulf's flaws render him all the more heroic; in some respect, there could be no other ending, a hero must seek glory "and the undying value of a good name that lives on...after his death" (Kroll 129).

Works Cited:

- British Library Online Gallery. 2007. British Library. 30 September 2007. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/themes/englishlit/beowulf.html

- Chickering, Howell D. Jr., trans. Beowulf. New York: Anchor Books, 2006 ed.

- Kroll, Norma. "Beowulf: The Hero as Keeper of Human Polity." Modern Philology 84.2 (1986): 117-129.

- Niles, John D. "Reconceiving Beowulf: Poetry as Social Praxis." College English 61.2 (1998): 143-66.

- Niles, John D. "Understanding Beowulf: Oral Poetry Acts." The Journal of American Folklore 106 (1993): 131-155.

Return to Top

This web site was designed by Stacey Bieber as part of a class assignment for English 630ML: The Technology of Textuality. The author is solely responsible for the ideas and content contained herein. Moreover, no one may quote or use the ideas expressed herein without proper attribution to the author.