Beowulf Mini Web Project Assignment Page for Dr. Kleinman's Class

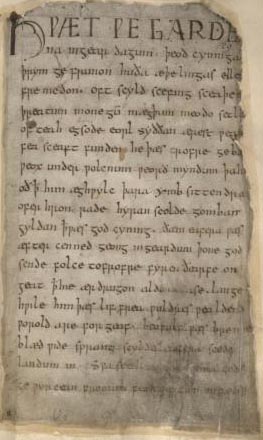

Beowulf is the first great heroic poem written in the vernacular, Old English, rather than Latin. It survives in only one manuscript, London British Library Cotton Vitellius A. XV. The manuscript (codex) contains five different works, and the only unifying feature of the works appears to be that they contain tales of monsters. Although there is no exact date assigned to the manuscript, it was most likely transcribed in approximately 1000A.D. The entire codex consists of 116 leaves, 70 of which comprise the Beowulf poem (Chickering 245).

The early history of the codex is unknown, however, its ownership can be traced back to Lawrence Nowell, Dean of Litchfield in 1563. Subsequently, in the 17th century, Sir Robert Cotton obtained the codex. The codex was moved to Essex house in the Strand, then to Ashburnham House in Westminister (British Library Online Gallery). While in Ashburnham House a fire broke out in the library destroying a good portion of the library and damaging the manuscript. Following the 1731 fire, Sir Cotton's heirs deposited Beowulf and other important manuscripts in the British Library. In 1786, Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin made two transcriptions of the poem. Although, Thorkelin's translations contain transcriptional errors, they still "are invaluable for determining letters and words which have since crumbled away" (Chickering 246).

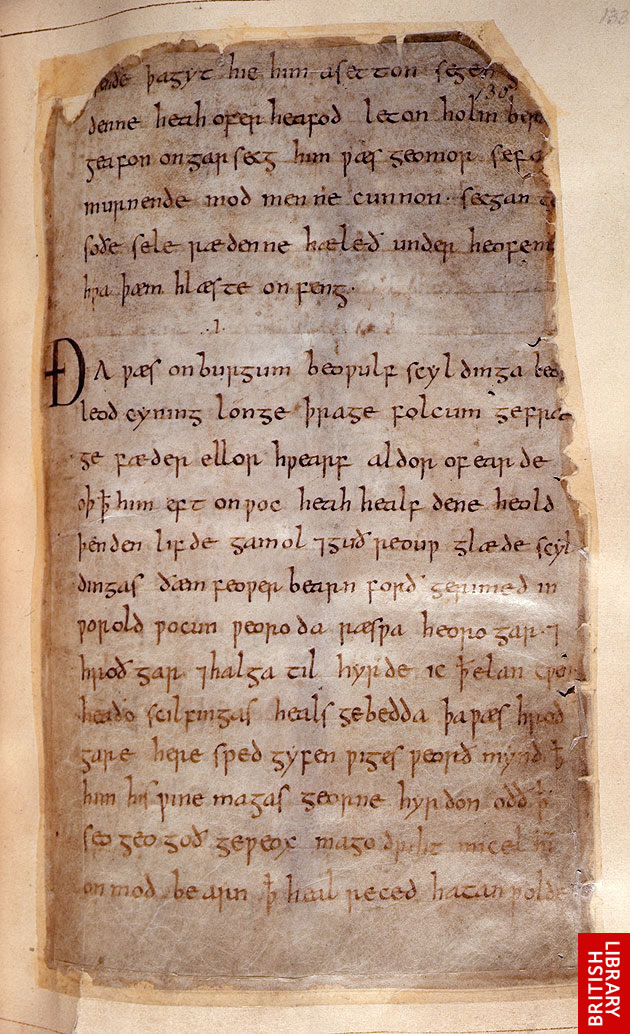

The most damaged section of the manuscript are the leaves containing lines 1685-2339 and the last leaf of the poem (246). In addition to the fire damage, many letters of the manuscript have faded due to excessive wear. In 1845, in an attempt to preserve the manuscript, the leaves were mounted in paper frames. Although the intent was to preserve the pages from further damage, the frames covered some letters of the text; these letters were later revealed through special infrared and ultraviolet light technologies. Additionally, computer imaging was used to further enhance the readability of the text.

In 1993, the British Library began the Electronic Beowulf project. Using the latest technologies, pictures of the medieval manuscript were compiled into an electronic version of the manuscript, which permits readers to place leaves side by side for reading, as well as enabling them to examine the type and quality of the vellum employed (British Library Online Gallery). Unfortunately, this electronic version is only available for purchase on CD. Thus, for most students, access to the original manuscript is only readily available to the first leaf of the poem. Nevertheless, many of the comments regarding the first page can be applied to the other pages of the manuscript.

The Cotton Vitellius A. XV MS is small in size, measuring five by eight inches, and quite simple in its presentation (Chickering 246). It appears to be the work of journeyman, with poorly made capital letters and no illuminations. The poem "is written in the unrhymed four-beat alliterative meter of Old English poetry", consists of 3,182 lines, and is divided into forty-three sections. Since the divisions do not reveal clear chapter breaks, it is believed that they were a scribal addition (1). As can be seen in the image, the edges of the transcript are charred from the fire, with some words and letters being totally eradicated. Moreover, it does appear that the scribe utilized pointing to indicate the end of metrical lines. Since Beowulf exists in only one manuscript, there are no other versions of the text with which to compare the reliability of the transcription. Moreover, as the manuscript is damaged (both from the fire and wear and tear) editors have had varying emendations of the text.

Lines 3076-3086 of Beowulf have received much attention from literary scholars. In these lines, Wiglaf addresses the Geats stating:

Wīglāf maðelode, Wīhstānes sunu:Howell D. Chickering, Jr.'s translation reads:

"Oft sceall eorl monig ānes willan

wræc ādrēog[an], swā ūs geworden is.

Ne meahton wē gelæran lēofne þēoden,

rīces hyrde ræd ænigne,

pæt hē ne grētte gold-weard þone,

lēte hyne licgean þær hē longe wæs,

wīcum wunian oð woruld-ende;

hēold on hēah-gesceap. Hord ys gescēawod,

grimme gegongen; wæs pæt gifeðe tð swīð,

þe ðone [þēod-cyning] þyder ontyhte. (3076-3086)

Wiglaf addressed them, Weohstan's son:Wiglaf's speech is quite ambiguous, and, thus, open to several interpretations. For example, whom is the "one" of which Wiglaf speaks. It has been argued that the one is: (1) the thief, who stole from the hoard causing the awakening of the dragon, (2) the dragon, whose actions cause Beowulf to fight him, or (3) Beowulf, whose imprudent decision to attempt to vanquish the dragon results in his demise. However, as Chickering states "[t]he lines following the bell-like ān are too exclusively focused on Beowulf's rash leap toward glory" to not believe they pertain to Beowulf (376). Thus, concluding that Wiglaf is speaking of Beowulf, one must decide whether Wiglaf's speech is an inditement of Beowulf's actions, or, rather is it merely Beowulf's fate that he will die a hero's death. Perhaps it is a little of both--Beowulf did act imprudently, yet he exemplifies those Anglo-Saxon qualities idealized in a hero. Moreover, as the culture mandates that "every hero must make as good a death as he can" this death (or another like it) was Beowulf's inescapable destiny(376).

"Often many earls must suffer misery

through the will of one, as we do now.

We could not persuade our beloved leader,

our kingdom's shepherd, by any counsel,

not to attack that gold-keeper,

to let him lie where long he had lain,

dwelling in his cave till the end of the world.

He held to his fate. The hoard has been opened

at terrible cost. That fate was too strong

that drew [the king of our people] toward it.

In his article, "Reconceiving Beowulf: Poetry as Social Praxis", John D. Niles states that one of the functions of oral poetry was to acculturate the Anglo Saxon aristocrats. Thus, oral poetry "constitute[s] a praxis affecting the way people think and act" (Niles 143). Additionally, Niles claims that one of the functions of Beowulf would have been educative, as schools were primarily for the ecclesiastical class (151). Beowulf "would have offered Anglo-Saxon aristocrats memorable profiles in courage" as well as an understanding of "the need for generosity, moderation, and restraint on the part of the rulers" (152). Taken in this context, not only would Beowulf serve as an exemplar on how one should behave with both courage and honor, but also as a cautionary tale, instructing that sometimes personal heroics need to be subsumed for the good of the kingdom. Despite his fate in the poem, Beowulf still serves as a positive role model, especially when contrasted against "the characters who figure as foils" to him (153).

For example, Wiglaf refers to Beowulf as their "beloved leader" (Beowulf 3079). The listener would reflect upon the positive attributes we have learned of Beowulf throughout the poem: his ability to keep peace within the kingdom, his generosity as a ring-giver, and his early heroism. His virtues are extolled throughout the poem, and become even more apparent when compared to the actions of characters such as Heremond, who led his people into needless warfare and sorrow (901-06), and Modthrytho, whose actions were not queenly (1931-43). Thus, "the poet invites his audience to emulate the positive example" of Beowulf and "scorn the negative" examples of the others (Niles 153).

Yet, Beowulf is not perfect, as a human he is flawed. When Wiglaf opines, "[o]ften many earls must suffer misery through the will of one" (Beowulf 3077-78) we are reminded of Beowulf's past boastfulness and eagerness to be recognized for his heroic deeds. In fact, Hrothgar warns "Beowulf against two typical character flaws, avarice and pride" (Chickering 332). Moreover, Hrothgar chose not to fight Grendel because he had a responsibility to his kingdom and also recognized his limitations due to his advanced age. Based upon this warning and Hrothgar's own actions, one can argue that Beowulf has succumbed to pride and his need for glory. Certainly, his desire to prove that he was still able to defeat the dragon (as he had Grendel and his mother) could have led to his imprudent decision to fight the dragon. Regardless, of the end result, Wiglaf admires and loves his lord, thus, concluding that he was good king. In the end, Beowulf's flaws render him all the more heroic; in some respect, there could be no other ending, a hero must seek glory.

Works Cited:

British Library Online Gallery. 2007. British Library. 30 September 2007. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/themes/englishlit/beowulf.html

Chickering, Howell D Jr., trans. Beowulf. New York: Anchor Books, 2006 ed.

Niles, John D. "Reconceiving Beowulf: Poetry as Social Praxis" College English 61.2 (1998): 143-66.

This web site was designed by Stacey Bieber as part of a class assignment for English 630ML: The Technology of Textuality. The author is solely responsible for the ideas and content contained herein. Moreover, no one may quote or use the ideas expressed herein without proper attribution to the author.