|

|

|

The Chance of the

Moment: Coffee and the New West Indies Commodities Trade

Michelle Craig

McDonald

|

IN

January 1773 Captain John Ash wrote to his financial backers, the

Liverpool-based firm Brown & Birch, of his safe arrival in the

Caribbean. He also informed them of a change in plans. Contracted to secure

a cargo of wood and mules, Ash tried first in British Tortola and then in

Danish Saint Thomas without success. He sailed next to the Spanish colony

of Puerto Rico where he reported: "We loaded what of the wood we could

get there and sent express to the out bays near us, who returned for

answer, that there was very little and so situated that we could not get at

it either with ship or boats ... we proceeded then to another design for we

found neither wood nor mules, but a good deal of coffee."1 Jamaicans were unlikely to buy Ash's

coffee when he returned to Kingston because they produced enough of their

own, yet he purchased between two and three thousand pounds, reasoning it could

be resold in North America to offset the expense of his endeavor.

|

1

|

|

A decade later many more merchants and ship

captains were discovering, as Ash had learned, the lucrative potential of

coffee trading. Demand for coffee in the United States grew rapidly after

1783, both as an article of home consumption and as one of the new nation's

most profitable reexported commodities. The postrevolutionary coffee trade

illustrates the importance of the West Indies to early American economic

development and the increasingly international orientation of United States–Caribbean

trade. Focusing on coffee helps revise the work of earlier historians who

argued that, with barely a lull, Britain reemerged as America's foremost

trading partner and continued to dominate the new nation's financial

landscape. "Only very slowly did the United States advance out of its

colonial economy," suggested John J. McCusker and Russell Menard in The

Economy of British America. "The decade immediately following the

end of the war looked economically much the same as the decade preceding

it, in basic structure, if not in detail."2 Yet it is in the details that

differences are most apparent. Trade to Europe may have resumed along

familiar lines, but McCusker and Menard underestimated the profound changes

in West Indian commerce after 1783.

|

2

|

|

Before the American Revolution, most coffee

entering North America originated in British Jamaica or, after 1763, the

ceded islands of Grenada, Saint Vincent, and Dominica, and arrived through

Philadelphia. Parliament's decision to enforce the Navigation Acts on

United States trade after American independence, with "regulations by

which the exportation of sugar and coffee, from those [West Indian]

colonies, in American vessels, is generally prohibited," irrevocably

altered this pattern, and did so at a time when the American coffee

business was booming. Philadelphia continued to dominate North America's

coffee import market, but the city's merchants shifted from British to

non-British, especially French, suppliers (Figures

I–II). By

1802 the value of British West Indian coffee coming into the United States

amounted to no more than $1 million, whereas revenue from other parts of

the world rose to more than $8 million.3

Coffee's rapid ascent and prominent place among America's reexport trades

makes it one of the best case studies to gauge how ably and quickly

American merchants could navigate the volatile commercial and legal

networks of a postrevolutionary Atlantic world where, to succeed, traders

needed to be able to reallocate resources quickly (Table

I).

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure I

State-by-state breakdown of pounds of coffee

imported into the United States with percentage of total trade, October

1790 to December 1791, compiled from American State Papers:

Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United

States, Commerce and Navigation (Buffalo, N.Y., 1998), 1: 203.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure II

State-by-state breakdown of pounds of coffee

imported into the United States with percentage of total trade, October

1791 to December 1792, compiled from American State Papers: Commerce

and Navigation, 1: 163.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table I

Coffee Imports in Pounds into Pennsylvania by Region, including Percentage

of Total Trade, 1789–91

|

|

|

1789–90

|

1790–91

|

|

|

|

|

British West Indies

|

323,623

|

155,222

|

|

|

(23.2%)

|

(10.7%)

|

|

|

French West Indies

|

826,663

|

1,180,180

|

|

|

(59.4%)

|

(81.0%)

|

|

|

Bourbon and Mauritius

|

26,171

|

—

|

|

|

(1.9%)

|

—

|

|

|

Spanish West Indies

|

2,986

|

24,914

|

|

|

(0.2%)

|

(1.7%)

|

|

|

Floridas and Louisiana

|

8,554

|

—

|

|

|

(0.6%)

|

—

|

|

|

Dutch West Indies and

|

|

|

|

|

American Colonies

|

110,750

|

82,086

|

|

|

(8.0%)

|

(5.6%)

|

|

|

Cape of Good Hope

|

—

|

13,064

|

|

|

—

|

(0.9%)

|

|

|

Danish West Indies

|

75,947

|

—

|

|

|

(5.5%)

|

—

|

|

|

Swedish West Indies

|

17,545

|

1,692

|

|

|

(1.2%)

|

(0.1%)

|

|

|

Totals

|

1,392,239

|

1,457,158

|

|

|

(100.0%)

|

(100.0%)

|

|

|

|

|

Source: American State

Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 83, 179.

|

|

|

|

The riskiest way to deal

with complex regulations was to evade them through smuggling. Ash saw

advantages to this alternative in 1773, but also advised Brown & Birch

of some potential problems. Coffee was among Puerto Rico's principal

exports, yet Ash had nonetheless faced significant competition. He

described a "coast ... full of vessels that can supply them on better

terms than we," and suggested carrying at least one-third to

one-fourth the purchase price in cash as well as an "assortment of

very fine goods." Puerto Rican sellers had demanded payment in full in

goods or currency, and were unwilling to trade for samples—examples of

goods from future harvests—that Ash normally used to conduct business.

He also noted that his vessel, the Mary, drew too much draft for

Puerto Rico's shallow harbors. Ferrying coffee from coast to ship had

required thirteen of his "best men" to leave the ship, with the

remaining crew unguarded, "waiting the lucky or unlucky chance of a

moment."4

Ash recommended using hired hands to transfer goods in shallops, or flat

boats, from bays to larger ships anchored offshore. More laborers would

increase expenses. Yet Ash strongly advised the investment in local

manpower.

|

4

|

|

Some American merchants

continued smuggling after the Revolution, but many more evaded the spirit

of the law as they tenuously conformed to its strictures. These men seized

the chance of the moment to expand their businesses through international

competition and legal loopholes. At the close of the eighteenth century, the

British, French, and Spanish Caribbean all produced coffee, and the neutral

holdings of Denmark, Holland, and Sweden offered free ports that broadened

the possible trajectories of America's coffee investments further still (Figure

III).5

Because of the number of competing suppliers, coffee turned out to be less

a tale of contraband commerce than a story about when and why smuggling

would not have been necessary or profitable. The overwhelming success of

the American coffee trade in the decades after independence exemplifies

these opportunities and merchants' abilities to make the most of them.

|

5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

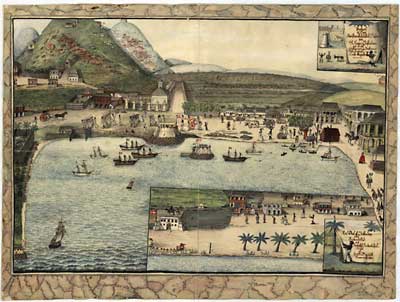

Figure III

H. G. Beenfeldt, The Port of Christiansted,

1815, watercolor, 30.0 cm x 41.0 cm. Three-masted schooners and

two-masted brigs and snow-brigs lie at anchor in the foreground, as do

two single-masted cutters (small coastal vessels used for local

transport). Fort Christiansvaren appears in the center of the image,

with troops practicing musters behind. To the left of the fort are the

town church and customshouse, where all shipments arriving into or

leaving the port were weighed and recorded. To the right is a cargo

being prepared for transport.

Large barrels arrive by oxcart. These could be

butts and hogsheads if carrying rum and hold 108 and 54 gallons,

respectively. If transporting sugar, they are likely tons, which could

hold twenty hundredweights, or roughly 2,240 pounds. Smaller barrels,

hundredweights or quarters, transported coffee and molasses as well as

sugar; hundredweights ran 112 pounds each, quarters were, as the name

implies, one-fourth that size, or 28 pounds each. Coffee could also be

shipped in bags or, in very small quantities, appear as individual

pounds. Courtesy, Danish National Archives, Copenhagen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trade in tropical commodities was profoundly affected by

the outbreak of the American Revolution. The British West Indies were key

players in the economies of most North American port cities before the war,

accounting for 20 to 35 percent of all inbound and outbound vessels to

Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston from 1768 to 1772 (Table

II).

Political theorist Edmund Burke described the relationship between the

colonies of North America and the Caribbean as "so interwoven that the

attempt to separate them would tear to pieces the contexture of the whole

and, if not entirely destroy, would much depreciate the value of all the

parts" of Britain's economic empire. The commercial disruptions caused

by war substantiated Burke's predictions. Though Britain tried to supplant

American trade after 1776, its efforts fell woefully short; ships from the

British Isles arrived only sporadically in the West Indies and often with

cargoes that colonial residents deemed entirely insufficient. Food

shortages repeatedly ravaged the Leeward Islands because of their proximity

to foreign colonies, the sugar monoculture, and a reliance on external food

supplies. On Montserrat whites and slaves alike suffered from malnutrition:

"for three successive Days, Hundreds of People came to Town in search

of ... a Morsel of Bread & returned Empty." And though Governor

Hay of Barbados wrote Parliament that supplies were more than adequate,

members of the British navy disagreed; General William Howe, in charge of

military operations in North America during the Revolution, found almost no

provisions on the island: "They have not ... a single cask of salt

provisions ... and are in the greatest want."6

|

6

|

|

Table II

Comparison of the Caribbean Provision Trade for Leading Colonial Port

Cities, 1768–72 (values given in tons and percentage that represents a

city's total trade in that year)

|

|

|

Boston

|

New

York

|

Philadelphia

|

Charleston

|

|

|

|

1768 inbound

|

10,811

|

6,301

|

11,677

|

8,238

|

|

(33.8%)

|

(28.8%)

|

(33.3%)

|

(26.1%)

|

|

1768 outbound

|

10,095

|

6,981

|

12,019

|

5,808

|

|

(29.9%)

|

(9.6%)

|

(32.1%)

|

(18.4%)

|

|

1769 inbound

|

10,495

|

6,964

|

11,726

|

6,123

|

|

(25.9%)

|

(25.9%)

|

(27.6%)

|

(21.0%)

|

|

1769 outbound

|

8,995

|

5,446

|

11,114

|

5,807

|

|

(24.2%)

|

(20.1%)

|

(27.1%)

|

(18.6%)

|

|

1770 inbound

|

11,088

|

8,695

|

14,946

|

9,563

|

|

(28.9%)

|

(34.0%)

|

(31.5%)

|

(34.7%)

|

|

1770 outbound

|

8,248

|

7,005

|

13,842

|

7,374

|

|

(22.3%)

|

(26.3%)

|

(29.5%)

|

(24.6%)

|

|

1771 inbound

|

8,586

|

8,191

|

13,397

|

8,208

|

|

(21.7%)

|

(32.7%)

|

(32.1%)

|

(26.8%)

|

|

1771 outbound

|

9,171

|

7,708

|

13,449

|

6,131

|

|

(23.6%)

|

(30.2%)

|

(31.2%)

|

(19.6%)

|

|

1772 inbound

|

12,649

|

8,170

|

12,947

|

6,121

|

|

(29.0%)

|

(28.3%)

|

(30.6%)

|

(20.4%)

|

|

1772 outbound

|

10,073

|

8,076

|

15,674

|

5,749

|

|

(23.7%)

|

(28.7%)

|

(34.2%)

|

(18.2%)

|

|

|

|

Source:

Summaries of topsails, sloops, and tonnage for the foreign and British

West Indies for each year, Customs 16–1—America,

1768–1772, National Archives, Kew, Eng.

|

|

|

|

When the war ended, many

in North America and the British Caribbean hoped business would return to

normal, yet two stumbling blocks stood in the way. First, United States–British

West Indian trade using American vessels was banned; second, shipments to

the United States were to be taxed as foreign exports. The latter issue was

more easily resolved. A July 2, 1783, order in council authorized the

exportation of coffee, rum, sugar, molasses, cocoa nuts, ginger, and

allspice to the United States and the importation of American lumber,

flour, bread, grain, vegetables, and livestock under the same tariff

regulations as British colonies; though these commodities could now move to

and from the United States, they could still do so only on British vessels.7

|

7

|

|

Several of the island

governments protested. The Assembly of Barbados sent petitions to the

Society of West India Merchants and Planters in London, decrying the

limitations on American commerce as untenable and ruinous. Jamaica's

planters warned Governor Archibald Campbell that refusal to allow American

shipping would result in not only food shortages but also a lack of lumber

to build shipping casks, hindering planters' ability to ship local produce

abroad. When Campbell rejected their requests, Jamaican planters also

turned to the Society of West India Merchants, which rallied behind their

cause, arguing for the reinstitution of prerevolutionary patterns of trade

and requesting permission for free intercourse on American vessels. Their

appeals to Parliament, however, were as unsuccessful as those from

Barbados. Jamaica's House of Assembly tried again in November 1783,

petitioning the governor to permit American shipping for at least a

transition period of nine months, but Campbell downplayed their fears,

replying: "I flatter myself, however, that from the early and repeated

applications I have made to the Governors of Nova Scotia and Canada, for an

immediate supply of such articles as we most want in this country, and from

the encouragement given to British merchants, the articles enumerated in

your address will soon be lowered in their price, and the apprehensions of

a scarcity happily removed." Particularly galling to the more

established British islands of Jamaica and Barbados, Parliament gave

limited free port status to the former French islands of Dominica, Grenada,

and Saint Vincent in compensation for occupation during the American

Revolution. Planters bitterly complained that, rather than bolster the

islands' own economies, free port status instead facilitated the

clandestine importation of French coffee and sugar, especially from Saint

Domingue. "Above 20 times the quantity of produce," they grumbled,

"has been exported from these islands since their conquest than ever

grew upon them."8

|

8

|

|

As privation in the

Caribbean colonies grew, some island governors proved more sympathetic than

Campbell. Though official policy excluded American ships from trading in

British West Indian harbors, governors could grant special concessions, or

the temporary suspension of certain parts of the Navigation Acts, when

doing so was deemed essential to a colony's well-being. As might be

expected, the mother country and its colonies often defined essential and

well-being differently, yet the practice nonetheless became so widespread

that, in 1786, Parliament passed an act of indemnification to annually

exempt governors from prosecution for Navigation Act violations.9

|

9

|

|

Governors suspended the

Navigation Acts for various reasons. In a few cases, such as that of

Barbados, successive governors simply prolonged special concessions

indefinitely by extending the original document each time it was due to

expire. Other governors responded to genuine need. Though Governor Campbell

of Jamaica was unwilling to suspend the ban on American shipping in 1783, a

series of earthquakes and hurricanes during the next three years forced his

successor, John Dalling, to reconsider this position. The Pennsylvania

Gazette report on the first of these hurricanes described the

devastation of the island's southern port cities in July 1784: "The

harbour of Kingston and Port-Royal, on the morning after the hurricane,

exhibited the most striking picture of desolation: His Majesty's ships Janus

and Iphegenia, the Vernon armed store-ship, Nelly (Dawson) and some small

craft, being the only vessels that rode out the storm. Every other in these

harbours were either sunk or driven ashore, and all of them dismasted. To

give perfect account of the loss is a task at present, impossible; many

vessels being absolutely sunk, of which no vestige remains, but the heads

of masts that appear above water." Even under true duress, however,

Dalling lifted only the ban on imports of American food and lumber; the prohibition

on British West Indian exports to the United States in American ships

remained in effect.10

|

10

|

|

Special concessions

artificially reinstated some lines of prerevolutionary commerce between

North America and the British Caribbean. They ensured that American food

and supplies reach the West Indies, but were less successful in supplying

American merchants with the tropical commodities their growing reexport

businesses demanded. Richard Henry Lee lauded the lobbying efforts of

British and American merchants in London to lift "all the silly,

malign commercial restraints upon our trade with their [British] W. India

Islands," yet most politicians were more pessimistic. Benjamin

Harrison, of Virginia, cautioned that "the determinations of the ...

English respecting our [W. Indies] trade is really alarming and in the end

will prove ruinous to us if not counteracted." Thomas Jefferson

worried that "commerce is got & getting into vital agonies by our

exclusion from the West Indies," and James Madison concluded that

"we have lost by the Revolution our trade to the West Indies, the only

[branch] which yielded us a favorable balance of trade without having

gained new channels to compensate it." When diplomatic negotiations

failed to produce desired results, America responded to British

restrictions with financial retaliation. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and

Rhode Island all banned British vessels from loading American goods onto

their vessels or from unloading American produce from one state into

another state under penalty of condemnation. Maryland, North Carolina, and

Pennsylvania imposed taxes for the docking of British vessels in their

ports, and most New England states added taxes to goods arriving by British

carriers. Almost all states applied higher duties to British sugar, coffee,

and rum than to their French counterparts. In 1789 Congress standardized

the arrangement, voting to impose "an increased duty of tonnage ... on

all foreign ships and other vessels that shall load in the United

States" arriving from places where "the United States are not

permitted to carry their own produce."11

|

11

|

|

Despite the best efforts

of American merchants and West Indian planters, the July 2, 1783, order in

council remained officially unchanged for almost a decade. The British

Caribbean colonies could legally import and export certain products, coffee

among them, yet more than three-quarters of prerevolutionary trade between

the two regions had been carried in American vessels. Parliament offered

the opportunity, but not the means, and the resulting cost of British

shipping increased the price of coffee enough to encourage American buyers

to look for alternatives. They had several options. Though Britain had

already declared itself uninterested in negotiating with the United States,

and France allowed only limited access to its Caribbean colonies in the

immediate postwar period, some hoped these restrictions would encourage

traders to look beyond traditional commercial comfort zones. "The

Dutch and Danes," John Adams asserted, "will avail themselves of

every error that may be committed by France or England. It is good to have

a variety of strings to our bow."12

|

12

|

|

It was reasonable for American merchants to expect a

warm welcome in Amsterdam, given the Netherlands' long-standing commercial

and military rivalry with Britain. The colonial officials of Dutch Saint

Eustatius had been the first governmental body to recognize the legitimacy

of North American claims to independence.13

Competition in the carrying trade, however, proved an intransigent barrier

in United States–Dutch trade relations in the Caribbean. Holland

agreed to allow American trade with its West Indian colonies of Saint

Eustatius, Curaçao, and Saint Martin, as well as the Dutch "colonies

upon the continent, Surinam, Berbice, Demarara, and Essequibo," which,

though "a greater distance from us ... can not subsist without our

[American] horses, lumber, and provisions." Yet the Dutch limited what

Americans could bring to the colonies and what they could take in return,

especially coffee and sugar. The United States could import Caribbean

coffee duty-free, but had to pay import taxes on East Indian coffees, and

ship all tropical commodities, except molasses, in Dutch vessels. Some

speculated that, though only molasses could be directly shipped in American

vessels, "quantities of sugar, coffee, and other produce are always

smuggled, as they say."14

Illegal trading may have supplied some coffee, but American merchants

continued their search for a reliable, legal source.

|

13

|

|

Benjamin Franklin, acting

in 1782 as a member of a European-based commission appointed by Congress to

reopen commercial and diplomatic relations, approached the Portuguese

ambassador. He inquired about potential American trade with Brazilian

coffee plantations, but was told that Portugal "admitted no nation to

the Brazills." Franklin tried a different tack, asking if the United

States might use Portugal's "Western Islands," such as Madeira or

the Canaries, as a "depot" for importing Brazilian "sugars,

coffee, cotton, and cocoa." The Portuguese ambassador responded

enthusiastically, suggesting that, if approved by his government, "they

could furnish us [the United States] with these articles at Lisbon fifteen

per cent cheaper than the English could from their West India

Islands." Unfortunately, the Portuguese court rejected the proposal.15

|

14

|

|

The commission also

appealed to Spain. Another member of the commission, John Adams, wrote the

Count de Sanafee, Spain's Paris-based minister, in August 1783 to ask

"whether it might not be possible to persuade his court that it would

be good policy for them to allow ... the United States of America a free

port in some of their islands at least, if not upon the continent of South

America?" Sanafee's response was vague; rather than address the legal

and diplomatic aspects of commercial ties between the United States and

Spain, he insinuated that "his court would be afraid of the

measure" as "free ports were nests of smugglers" and

"afforded many facilities of illicit trade (le commerce interlope)."

Adams countered with an alternative similar to the one Franklin had offered

Portugal. If American ships could not directly import Spanish colonial

coffee, could the produce "be carried to the free ports of France,

Holland, and Denmark, in the West Indies ... in Spanish vessels, that they

might be there purchased by Americans?" Sanafee simply replied that

"he could not pretend to give any opinion upon any of these points,

but that we must negociate them at Madrid."16

|

15

|

|

Having exhausted the most

likely suspects, the United States Commissioners' quest for tropical

trading partners led them to some very strange bedfellows indeed. In 1784

the Pennsylvania Gazette hinted that a commercial treaty between the

United States and Russia might be in the offing. Though Russia did not

possess a West Indian colony at the time, according to "letters from

Holland ... a negociation is on foot between the Empress of Russia and

their High Mightinesses the States-General" for the "ceding to

the former (for an equivalent) an island in the West-Indies (believed to be

Saint Martin's)." Russia, the article suggested, had "long wished

for a settlement in the Mediterranean and West-Indies" to "extend

that commerce which they have lately laid plans for carrying on to every

part of the globe."17

|

16

|

|

Saint Martin was the

smallest shared colony in the Caribbean. Holland controlled sixteen square

miles and the port city of Philipsburg in the south; France, the remaining

twenty-one square miles to the north. Adams included the tiny divided

colony in the commission's list of possible West Indian partners in 1783,

but noted, "Saint Martin is divided between the French ... and the

Dutch," and with few established towns and less successful

agriculture, "it does not flourish." Even if Russia had been

successful, Saint Martin could not have produced the coffee American

traders desired; at best it may have been a clearing station, similar to

Dutch Saint Eustatius or Danish Saint Croix, for redistributing the riches

of the region beyond the legal limitations of metropolitan policies.18

The Pennsylvania Gazette article unfortunately recorded only

Russia's West Indian ambitions, and not Holland's response. In January 1785

larger events—Holland's alignment with Prussia to declare war on

Austria and Russia—would intercede before any possible sale could be

completed.

|

17

|

|

American coffee traders,

especially those in Philadelphia, had better success in the Danish

Caribbean colony of Saint Croix (Figure

IV).19

Almost all Philadelphia-bound coffee shifted to the Saint Croix port of Christiansted

in 1781 and 1782, and nearly all other commodities imported into

Philadelphia followed suit. The volume and variety clearing this one port

obviously meant these goods were Danish reexports, since Saint Croix did

not produce the western and southern European wares packed beside the

sugar, molasses, coffee, and rum headed to Philadelphia.20

American interests in Saint Croix were admittedly fleeting, yet Christiansted

played a key role for the brief time between British prewar supplies and

French free ports of the mid-1780s. The Danish crown briefly attempted to

assert a royal monopoly on the colony's shipping in 1781, yet the

reassertion of Saint Croix's neutral status in 1782 and 1783 made it the

ideal clearinghouse, not only for coffee bound for Philadelphia but also

for almost everything else as well. Table

III

compares the numbers of ships that sailed from Christiansted with those

from other ports and demonstrates that, though almost three-quarters of the

ships carrying coffee to Philadelphia in 1781 arrived from Saint Domingue,

more than 60 percent switched to Christiansted in 1782. Most ships

continued to come from Saint Croix during the first quarter of 1783, though

by June Cap-Français and Port-au-Prince reemerged as principal coffee

shippers.21

|

18

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure IV

At approximately eighty square miles (or

twenty-six miles long and seven miles wide), Saint Croix is the largest

of the West Indian colonies settled by Denmark. Christiansted is its

largest port and served briefly as the capital of the Danish West

Indies in the eighteenth century. Saint Croix is located thirty-five

miles south of Saint Thomas and Saint John, and approximately eighty

miles southeast of Puerto Rico. Its principal industries were sugar and

rum, though the island served as a strategic reexport port for a much

wider range of commodities. Drawn by Rebecca L. Wrenn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table III

Numbers of Ships into Philadelphia from Principal Ports, 1781–83

|

|

|

|

1781

|

1782

|

1783

|

|

|

|

Danish ports

|

|

Christiansted, Saint Croix

|

15

|

126

|

66

|

|

Saint Thomas

|

10

|

5

|

15

|

|

French ports

|

|

Cap-Français, Saint Domingue

|

22

|

1

|

13

|

|

L'Orient, Saint Barthélemy

|

6

|

6

|

—

|

|

Port-au-Prince, Saint Domingue

|

10

|

4

|

12

|

|

British ports

|

|

London, England

|

—

|

—

|

12

|

|

Spanish ports

|

|

Cadiz, Spain

|

11

|

1

|

—

|

|

Havana, Cuba

|

44

|

20

|

13

|

|

Portuguese ports

|

|

Lisbon, Portugal

|

—

|

—

|

10

|

|

American ports

|

|

Bordentown, N.J.

|

—

|

—

|

22

|

|

Boston

|

6

|

2

|

15

|

|

Hamburg, Pa.

|

—

|

47

|

1

|

|

New Castle, Del.

|

14

|

5

|

7

|

|

Lewistown, Maine

|

1

|

1

|

12

|

|

New Jersey

|

4

|

20

|

12

|

|

New York

|

—

|

—

|

50

|

|

Rhode Island

|

3

|

1

|

10

|

|

Wilmington, Del.

|

16

|

18

|

11

|

|

All other ports

(overall)

|

29

|

32

|

244

|

|

|

Total number of inward clearing vessels

|

191

|

289

|

525

|

|

|

|

Notes:

The year 1783 includes only the first three quarters. Only ports with ten

or more vessels in a given year are specified by name. For a complete

listing of all ports engaged in Philadelphia's coffee trade, see footnote

21.

|

|

Source:

Records of the Office of the Comptroller General, Port of Philadelphia

Records, Registers of Duties Paid on Imported Goods (1781–1788), 6

vols., Record Group 4, Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg, Pa.

|

|

|

|

France further enticed American business to its colonies

in 1784 and 1785 by opening five West Indian free ports, including three in

Saint Domingue, to American shipping and abolishing bans on the importation

of flour and other food staples. Historians have credited these relaxations

for the extraordinary rise in American exports to the French Caribbean by

the mid-1780s, but just as important for a burgeoning United States

tropical produce reexport business, American traders turned increasingly to

French colonies for their West Indian imports as well. For those dealing in

coffee, the decision is easy to understand. French coffee already had a

sound reputation for quality and taste, with many consumers preferring it

to British coffee even before the war. Moreover, in the 1780s and early

1790s, the French island of Saint Domingue ranked as the world's leading

coffee producer, resulting in a price economy of scale unrivaled by others.22

Had the application of Britain's tariff on foreign produce not artificially

inflated the price of French coffee to almost double that of British

manufacture, more French coffee would likely have made its way to American markets

before 1776. In February 1793 the French Council opened all its West Indian

ports to American vessels, fulfilling a decade-long objective in American

foreign policy. For the next ten years, with two important exceptions, the

French Antilles supplied from half to four-fifths of all coffee brought

into the United States.23

Even the two aberrations, 1798–99 and 1803, furnish good examples of

how rapidly American merchants shifted between coffee suppliers as well as

how quickly they could return to preexisting patterns of trade once crisis

was averted.

|

19

|

|

The first drop in French

coffee exports to America occurred during the Quasi War with France. In 1798

and 1799, the United States temporarily closed all trade to France and its

colonies in retaliation for increasing seizures of American ships on

charges of privateering. France's increased aggression came in reaction to

American efforts to reestablish commercial relations with Britain. Under a

draft treaty negotiated by John Jay, Britain agreed to relinquish its posts

in the American Northwest by July 1, 1796, but retained rights to trade

furs in the region. The British offered compensation for ships seized in

the West Indies as a result of their orders in council, though any

financial gains were offset by their requirement that the United States

recompense British creditors for prerevolutionary debts that remained

unpaid. Most troubling, however, the agreement required the United States

to forego its practice of neutral shipping during the current war between

France and England, and for two years after the war's conclusion. Moreover,

it opened British West Indian trade to American ships under seventy tons,

yet prohibited these ships from exporting coffee, sugar, cocoa, or cotton

to the rest of the world, or even to America itself. A treaty that asked so

much of the United States and gave so little reinvigorated widespread

hostility among merchants already predisposed against Britain. Congress

struck the provision on West Indies imports to America, though they

approved the treaty limits restricting American imports of

Caribbean-produced coffee, sugar, molasses, cocoa, and cotton to American

consumption and prohibiting reshipment of West Indies produce in American

ships "either from his Majesty's islands, or from the United States to

any part of the world except for the United States."24

This last provision severely compromised the contributions the British

islands could make to America's reexport trade in tropical goods.

|

20

|

|

Through a circular letter

to Congress, American importers bitterly expressed their dissatisfaction.

"Courts of France & Great Britain particularly the

latter, hath discovered the utmost Jealousy of the commercial

Prosperity of America," the importers wrote. "They have it in

contemplation not only to cramp & restrain our commerce, by prohibiting

an intimate & extensive intercourse between America and their West

India possessions, but to deprive us as much as possible of the carrying

trade by prohibiting any American Vessel from importing into G. Britain any

commodities, but those of the State to which it belongs."25

In this sense the Jay Treaty, intended to encourage American commerce with

the British Caribbean, had the opposite effect. Imports of British colonial

coffee for United States consumers increased slightly after 1796, yet

traders continued to base their overseas ventures on the coffee of other

nations.

|

21

|

|

The Jay Treaty posed

additional problems beyond the constriction of American trade routes. Once

news of the Anglo-American alliance reached Paris, France rejected claims

of United States neutrality, and began seizing American ships bound for

England. France had certainly accused the United States of privateering

before 1798. In the last quarter of 1796, for example, customs agents

indicted forty-four American ships for illegal trading in Saint Domingue

alone, but in 1797 more than three hundred American ships suffered this

fate, with Saint Domingue and Guadeloupe taking the most aggressive

stances. Rarely were ships' crews arrested or endangered; more often, port

authorities condemned ships accused of illegal activity or forced them to

sell their cargo before being permitted to leave port.26

|

22

|

|

During these two years of

strained French relations, American merchants used a variety of strategies

to fill the commercial gap. They did not return to former British Caribbean

suppliers; despite British legislative efforts, coffee exports from the

British West Indies actually decreased by 43.4 percent from 1797 to 1798.

Imports of British East Indian coffee rose slightly, but still amounted to less

than 1 percent of total imports. Philadelphia took some advantage of the

opportunity Spain offered from 1798 to 1799, increasing coffee imports from

Havana and other Spanish Caribbean ports by almost 4 million pounds during

these two years. Similarly, the Danish and Swedish West Indies also saw

modest growth in coffee exports to the United States, though their

positions relative to the American coffee trade overall remained low.27

|

23

|

|

Most American coffee

merchants turned instead to the Dutch West and East Indies. Whether the

coffee coming from the Dutch West Indies in 1798 had originated somewhere

else is difficult to determine. The Dutch produced some coffee, yet not in

quantities sufficient to account for the leap from 3.9 million pounds in

1797 to more than 10 million pounds the following year. It is possible that

Dutch merchants reshipped Saint Domingue coffee to the United States during

the Quasi War. Though the United States cut off trade relations with the

French colonies, the Dutch did not, and some Philadelphia buyers complained

that Dutch competition drove up the price of French West Indian coffee.

"There are other things that attend this [coffee] trade, that should

not pass unnoticed: The Danes, or rather Dutch, under Danish colours, are

powerful and jealous competitors for a share in this commerce: Their flags

being also neutral, they swarm here [Saint Domingue] from St. Thomas's

& c.—and ... endeavor to undersell us. The usual custom among the

sellers of this article, when they arrive in town, is, at first to go into

all the American stores and learn the highest price they will give, and

then go and sell to a Dane for six deniers more." Coffee shipped from

the East Indies was more likely of Dutch manufacture. From just under 2.5

million pounds in 1796–97, Dutch East Indies exports to the United

States rose to 6.4 million pounds in 1798 and almost 12 million pounds by

1800 (Table

IV).28

|

24

|

|

Table IV

United States Coffee Imports in Pounds by Caribbean Region, 1789–1806

|

|

|

Swedish

|

Danish

|

Dutch

|

British

|

French

|

Spanish

|

Other

|

Total

|

|

West

Indies

|

West

Indies

|

West

Indies

|

West

Indies

|

West

Indies

|

West

Indies

|

|

|

|

|

|

1794–95

|

329,342

|

428,596

|

2,586,783

|

5,001,930

|

43,464,561

|

492,817

|

1,656,947

|

53,960,976

|

|

1795–96

|

314,140

|

961,706

|

7,751,433

|

4,480,463

|

44,688,310

|

681,986

|

2,262,457

|

61,160,495

|

|

1796–97

|

392,551

|

943,880

|

3,783,313

|

1,695,665

|

37,164,707

|

867,768

|

4,643,618

|

49,491,502

|

|

1797–98

|

13,782

|

109,027

|

3,863,472

|

1,372,603

|

42,290,705

|

1,109,558

|

8,963,478

|

57,722,625

|

|

1798–99

|

175,213

|

2,033,108

|

10,345,612

|

778,571

|

4,918,422

|

3,919,287

|

7,817,357

|

29,987,570

|

|

1799–1800

|

101,604

|

605,304

|

3,862,539

|

805,041

|

26,055,184

|

2,918,108

|

13,042,165

|

47,389,945

|

|

1800–1801

|

97,254

|

1,631,963

|

1,993,444

|

1,188,795

|

37,975,598

|

680,103

|

13,816,747

|

57,383,904

|

|

1801–2

|

53,496

|

200,594

|

1,388,881

|

1,764,391

|

25,870,126

|

591,445

|

11,017,928

|

40,886,861

|

|

1802–3

|

327,384

|

417,034

|

723,501

|

1,899,734

|

8,658,088

|

452,349

|

4,350,403

|

16,828,493

|

|

1803–4

|

698,469

|

2,116,340

|

7,979,593

|

1,997,162

|

19,605,955

|

4,239,074

|

12,001,789

|

48,638,382

|

|

1804–5

|

273,442

|

2,390,745

|

992,853

|

289,206

|

27,453,284

|

5,411,664

|

18,048,130

|

54,859,324

|

|

1805–6

|

66,833

|

3,585,073

|

2,218,818

|

1,440,658

|

29,679,201

|

5,102,115

|

13,878,954

|

55,971,652

|

|

|

|

Source: American State

Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 350,

367, 394, 402, 434, 441, 464, 471, 478, 514, 521, 566, 576, 580, 629,

635, 676, 682, 706, 712, 757, 760.

|

|

|

|

Though Dutch East Indian

coffee levels remained high after 1800, those in the West Indies dropped as

soon as the United States reestablished trade relations with the French.

Again, within a year, merchants adjusted their commercial links and imports

from the Dutch Caribbean dwindled to their lowest point in 1802, whereas

imports from the French West Indies leapt from 5 million to 26 million

pounds and from there to almost 38 million pounds in 1800–1801. After

two years of the United States embargo, France agreed to end hostilities

and French colonial coffee imports climbed from 16 to 55 percent of total

American coffee imports.

|

25

|

|

The only other

significant drop in French Caribbean coffee imports occurred in 1803,

during the waning years of the revolution in Saint Domingue. When that

conflict erupted, the island dominated world production of sugar and coffee

and was a major supplier of indigo and cotton. Historians have focused on

the revolution's effect on the sugar industry, in large part because that

was where most destruction occurred, yet Saint Domingue's share of the

global coffee market was proportionately twice that of its share in total

sugar production, and coffee growing sectors of the island sustained less

damage and recovered more quickly. Did the United States import Haiti's

coffee and, if so, how did it balance commercial and diplomatic interests?

Officially, the United States refused to recognize the legitimacy of an

independent Haiti until 1862, though Presidents Washington, Adams, and

Jefferson all intermittently continued to permit travel to Haiti.

Ostensibly, most ships traveled under the guise of assisting Saint

Domingue's colonists during the slave revolution, but they rarely returned

empty-handed. More than once during the British occupation of Saint

Domingue, the need for supplies outweighed Britain's stance against United

States–French colonial trade. British military leaders repeatedly

opened the island's ports themselves, permitting payment for American goods

in locally produced sugar, coffee, rum, and cotton.29

Yet Haiti never appears in American customs papers as a port with which

American merchants conducted business; it is possible that, before 1804,

customs officials collapsed exports brought back from the island with those

from the rest of the French Caribbean, since regional sectors were rarely

divided by island (Figure

V).

|

26

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure V

Comparison of pounds of coffee imported from

the French colonies into the United States and total pounds of coffee

imported into the United States, 1795–1805, compiled from American

State Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 350, 367, 394, 402, 434,

441, 464, 471, 478, 514, 521, 560, 566, 576, 580, 629, 635, 676, 682,

706, 712.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Dutch once again

temporarily replaced French Caribbean coffee exports during the 1803

disruption. Dutch West Indian shipments to the United States rose by 7.2

million pounds, whereas those of their Indian Ocean colonies increased by

almost 7 million pounds. The balance, just over 7 million pounds, came from

an unlikely source—the French East Indian colonies of Bourbon

(present-day Réunion) and Mauritius. This coffee was clearly reexported

from French, British, and Dutch East Indian colonies, as 1803 was the only

year that any appreciable amount of coffee came through these two

locations. By 1804 patterns again reverted and, for the following two

years, the French West Indies produced almost half of all American coffee

imports and reexports single-handedly.

|

27

|

|

The last shift during the

period under consideration came in 1806 when the Spanish Caribbean and

Latin America finally supplanted the French Atlantic colonies, with much

longer repercussions, first as the United States' and ultimately as the

world's dominant coffee supplier. Commercial and diplomatic relations

between the Spanish colonies and the United States also had a complicated

history. During the closing years of the American Revolution, Philadelphia

established a thriving commerce with Spanish possessions, especially

Havana; forty-four vessels arrived from that city to Philadelphia in 1781,

representing the single largest concentration of Spanish shipping into any

North American port city, with twenty additional voyages the following year.30

But in 1784 Spain banned all trade to Cuba and the island's governor issued

orders for American boats to leave Havana immediately. When Spain reopened

Havana to United States shipping in 1785, American hopes were high.

Governor Count Galvez was considered a "confirmed friend of the United

States" who "proceeded to shew every favor to the Americans

there, by counteracting the very rigorous conduct of the former Governor of

Cuba towards our countrymen trading to that island." Galvez's

appointment in Cuba, however, was brief. He was transferred to Mexico and

his successor proved far less receptive to American interests.

|

28

|

|

Subsequent restrictions

against American shipping precluded any possibility of reviving a viable

American coffee trade until, along with Britain, Spain experimented by

reducing limitations in 1792 in an effort to attract American business away

from the French. When open trade policies did not produce immediate

results, however, Spain lost no time in again closing Havana's harbors. In

March 1792 the Pennsylvania Gazette reprinted an excerpt written by

an American merchant in Cuba, shocked at the immediacy of Spain's reversal

in trade policies. "Yesterday a most extraordinary order was issued by

the Governor relative to all foreign vessels in port; the most of them are

ordered away in six days, and the remainder in eight, so that no vessel can

stay longer than that time in harbour. This your own judgment will tell you

is the same as a prohibition to all strange vessels; and there is another

circumstance that makes the order doubly hard, which is, that all

foreigners who arrive must value themselves on a Spaniard, and all their

business transacted by him and in his name."31

|

29

|

|

Trade between Spain and

the United States remained negligible until 1798 when, for one year, Spain

again aligned with Britain to open its Caribbean and mainland ports to

American ships, with the stipulation that gold could not leave the Spanish

Empire under any circumstances. When it became clear that American vessels

consistently violated the ban, Spain rescinded the act and closed their

ports again the following year. In all likelihood the enormous imbalance of

trade between French and other nations' Caribbean colonies could not have

been rectified by the British and Spanish port openings of 1792 and 1798;

the French Caribbean continued to account for more American imports than

the colonies of any other empire before 1805 and, for many years in the

case of coffee, more than all other empires combined. But changes in

American shipping rights resulted in rapid mercantile reassessments and

realignments. When the French and British attempted to reassert control

over American shipping in 1806, Spain opted to open its ports to American

vessels. The result was an almost 400 percent drop in American imports of

French colonial coffee, and the Spanish West Indies, for the first time,

emerged as North America's dominant supplier (Table

V).32

The most dramatic developments in Spain's coffee industry were yet to come;

after the abolition of the slave trade and ultimately of slavery in the

French and British islands, the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of Puerto

Rico, Cuba, and especially Brazil dominated the global coffee market.

|

30

|

|

Table V

Percentages of Domestic and Foreign Coffee Importation, 1794–1806

|

|

|

Total coffee imports in

pounds

|

Percentage imported in

American vessels

|

Percentage imported in

foreign vessels

|

|

|

|

1794–95

|

53,960,976

|

—

|

—

|

|

1795–96

|

61,141,051

|

—

|

—

|

|

1796–97

|

49,491,502

|

93.5%

|

6.5%

|

|

1797–98

|

57,722,625

|

89.8

|

10.2

|

|

1798–99

|

29,978,570

|

—

|

—

|

|

1799–1800

|

47,389,946

|

91.3

|

8.7

|

|

1800–1801

|

57,383,904

|

88.3

|

11.7

|

|

1801–2

|

40,886,861

|

88.9

|

11.1

|

|

1802–3

|

16,828,493

|

79.4

|

20.6

|

|

1803–4

|

48,638,382

|

98.9

|

1.1

|

|

1804–5

|

56,141,320

|

80.5

|

19.5

|

|

1805–6

|

55,993,788

|

84.5

|

15.5

|

|

|

|

Note:

Imports by foreign and domestic shipping were not differentiated before

1797 or in the 1798–99 records.

|

|

Source: American State

Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 350,

367, 394, 402, 434, 441, 464, 471, 478, 514, 521, 566, 576, 580, 629,

635, 676, 682, 706, 712, 757, 760.

|

|

|

|

Given the legal and quasi-legal methods of importing

coffee, what role did the Captain Ashes of the world have to play after

America gained its independence? Philadelphia's newspapers included almost

weekly accounts of American ships stopped for suspected smuggling. For that

matter, French, British, and even Danish ships also appear in connection

with contraband coffee, though only a handful compared with the numbers of

vessels that legally entered the United States each year. Accounts of

coffee smuggling after the Revolution follow a pattern similar to what Ash

described in 1773, though none supplies as much detail. Ash's story after

he docked and unloaded his coffee is told by the Jamaican factors of Brown

& Birch, who wrote their Liverpool counterparts to confirm rumors that

the Mary had been condemned by Jamaican authorities for illegally

importing non-British coffee. It seems Ash miscalculated; rather than sell

his Spanish coffee in North America, he off-loaded his cargo in Kingston.

To undercut local producers, "Capt. Ash was imprudent enough to offer

coffee for sale in a publick company, under the current prices

considerably, which was taken notice of by a coffee planter there

present." Jamaican planters did not appreciate Ash's entrepreneurship

and reported the arrival of unlicensed foreign produce to local port

authorities who condemned the ship that same evening. When customs

officials boarded the vessel, they initially found only four casks of

coffee; after a more thorough examination, however, "the people's beds

[were] found full of beans" and notations on this concealment of cargo

turned up in the captain's log and first mate's journal, casting more than

a shadow of doubt on Ash's protestations of innocence. Brown & Birch

opted to pay the penalty for importing foreign coffee rather than forfeit

their ship; doing so also kept Ash out of prison, though they seemed less

concerned about his welfare than that of their vessel.33

|

31

|

|

The tactics used by

smugglers after 1783 would have sounded familiar to Ash, though the

definition of what constituted smuggling and the connotations of such

infractions differed in a postrevolutionary world. France and Britain tried

to influence American political allegiance by controlling the new nation's

trade routes. French ships stopped American vessels suspected of trading

with Britain and the British colonies and condemned the ship or confiscated

the cargo; British vessels did likewise to United States vessels in route

to France or the French West Indies. In February 1794, for example, the Pennsylvania

Gazette reprinted a letter from a merchant whose cargo, bound for

Bordeaux, was diverted to London. English merchants agreed to pay the going

rates for the ship's flour and rice, but a "quantity of coffee she had

on board, belonging to us, they were endeavoring to make French property

of."34

The following week an English judge condemned the ship's sugar and coffee

as French; according to British law, it was legally confiscated without

remuneration.

|

32

|

|

The news initiated a

backlash of public protest that argued British commercial incursions

threatened not only the American economy but also its international

reputation: "It can no longer be a doubt ... that the tendency

of certain measures is to shake the public credit of this country to the foundation—to

reduce the value of our exports more than one half ... to deprive us of

what every other nation has always considered as an advantage—our neutrality."

The efficacy of British efforts, however, depends on the reporter. In a

letter to Congress, President Thomas Jefferson made privateering seem

omnipresent: "Our coasts have been infested and our harbours watched

by private armed vessels ... They have captured, in the very entrance of

our habours, as well as on the high seas, not only the vessels of our

friends coming to trade with us, but our own also." Philadelphia's

merchants, by contrast, seemed more ambivalent. They accepted piracy and

privateering as inherent risks of transatlantic shipping; as long as

incidents remained sporadic and balance sheets ultimately fell in their

favor, the merchants were satisfied to count the increasing profits their

trade to the West Indies furnished:

That many of our vessels had been condemned in the West

Indies is certain; that others have been detained and ill treated, is

equally certain; that some have been legally condemned for breach of

revenue laws, cannot be denied; and that some have been falsely reported as

condemned, when they were not, is now well known. At any rate our shipping

is not all lost, as some would make us believe, for scarce a day passes,

without some arrivals from the West Indies, and this day there were five

reported on the coffee house books ... We are happy to hear that many of

our vessels from the West Indies return with full cargoes, or large sums of

money. 35

|

33

|

|

Those with principally

political or economic interests often interpreted the same events

differently. Jefferson's image of infested harbors says more about his

concerns for the acceptance of the United States in the international arena

and its ability to influence commercial activity, as well as about the

federal government's role as final arbiter of trade policies and

regulations, than it does about the economic realities surrounding the

complex issue of piracy in the era of the early Republic. The more

pragmatic attitudes of Philadelphia's merchant community better reflect how

the economic realities of trade had been restructured after independence.

Legislation from European powers determined who the United States conducted

business with, yet, rather than limiting traders' endeavors, such legislation

opened opportunities to explore and compare suppliers, to strike new

alliances, and to buy according to the best bargains. Philadelphia's

merchants did not assume an intractable position on issues such as piracy

and illicit trade. Occasional acts of depredation by pirates and privateers

were of far less consequence than the burgeoning trade on which these

piratical schemes preyed.

|

34

|

|

Michelle Craig McDonald is the Harvard

Business School Harvard-Newcomen Postdoctoral Fellow for 2005–6. She

would like to thank Alec Dun, David Hancock, Cathy Matson, Roderick

McDonald, Kathleen Montieth, Simon Smith, and an anonymous reader for the William

and Mary Quarterly for their close readings and suggestions, and Amanda

Moniz for alerting her to the case of Captain Ash at the National Archives

in Kew, England. A version of this article was presented at the Program in

Early American Economy and Society (PEAES) conference, "The Atlantic

Economy in the Era of 18th-Century Revolutions" in November 2003 and

benefited from the participation of those in attendance. Financial support

came from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, PEAES at the

Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Harvard University International

Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World.

Notes

1 Captain Ash to

Messrs. Brown & Birch, Jan. 24, 1773, T1/504, National Archives, Kew,

Eng.

2 John J. McCusker

and Russell Menard, The Economy of British America, 1607–1789

(Chapel Hill, N.C., 1985), 367.

3American State

Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United

States, 38 vols. (Buffalo, N.Y., 1998). The volumes of

greatest importance to this study are the first two volumes on Foreign

Relations and the two volumes on Commerce and Navigation. For Parliament's

decision to enforce the Navigation Acts, see American State Papers:

Commerce and Navigation, 1: 641. For a comparison of coffee imports

into several American states, see Figures I–II.

One-quarter of these imports were for American consumers; merchants reshipped

the balance to European markets. Percentages were derived by comparing

total coffee reexport revenue of $7,302,000 to total reexport revenue of

$28,533,000 for the years 1802 through 1804 as they appear in American

State Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 642. Put in comparative

perspective, by the turn of the century, American coffee reexport revenues

exceeded those not only of tea but also of sugar and molasses. In fact

coffee surpassed all Caribbean imports but rum in profitability, and was

second only to dry goods in global American reexports.

4 If a

ship captain arrived to trade without sufficient goods or credit on hand to

pay in full for what he wanted, as happened esp. in unplanned voyages such

as Captain Ash's trip to Puerto Rico, it was common to supply samples as

payment for trade with a promissory note for the balance. If demand was

sufficiently high, however, sellers might demand immediate payment or a

higher percentage of the total price rather than rely on the promise of

future compensation. For a discussion of the use of promissory notes in

eighteenth-century West Indian commerce, see Thomas M. Doerflinger, A

Vigorous Spirit of Enterprise: Merchants and Economic Development in

Revolutionary Philadelphia (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1986), 97–126.

Though admittedly later in the nineteenth century, examples of planters

using future crops as leverage for current buying power can be found in the

letter books of Marlborough Plantation, Manchester Parish, Jamaica, esp.

"Correspondence of Mrs. B. Boucher regarding Mr. R. Boucher's Coffee

Estate, Marlborough Plantation, Manchester, 1827–37" (MS 337),

and Hermitage Estate, Saint Elizabeth Parish, Jamaica, Letter book of John

Wemyss, Jamaica, 1819–24 (MS 250), both in the collection of the

National Library, Kingston, Jamaica. For Ash's comments on significant

competition, see Captain Ash to Messrs. Brown & Birch, Jan. 24, 1773,

T1/504, National Archives. The unlucky chance Ash most feared was discovery

by cruisers from the Spanish Main that regularly patrolled the waters

surrounding Spain's island colonies in search of illicit trade (T1/504, 2,

ibid.).

5

Though Philadelphia brought in some coffee from the East Indies and other

sources, most continued to arrive from the Caribbean islands, rising from

just under 4.5 million pounds in 1791 to more than 50 million pounds a

decade later (American State Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1:

203, 478, 512).

6

Figures for inbound and outbound vessels are based on Customs 16-1—America,

1768–1772, National Archives, reports of the Naval Officer submitted

annually to Parliament and permitting a comparison of basic import and

export data for all North American ports, the Floridas, and the Bahamas.

For a more specific breakdown by port city see Table

II. For Edmund Burke's description, see Herbert C.

Bell, "British Commercial Policy in the West Indies, 1783–93,"

English Historical Review 31, no. 123 (July 1916): 429.

For Britain's attempt to supplant American

trade, see "Lists of Imports in British Bottoms at Kingston, Jamaica,

during the War," T64/72, National Archives. The years of greatest

privation were 1776 to 1778, yet scarcities continued throughout the years

that followed. For discussions of the Jamaican House of Assembly's concerns

about staple imports, see House of Assembly, Jamaica, Journals of the

Honourable Assembly (Saint Jago de la Vega, Jamaica, 1811–1829),

7: 313, 314, 467, 577. For the effect on British West Indian production,

see "Imports into England from the West Indies, 1774–83,"

T38/269, National Archives. From 1775 to 1781, sugar production in the

British Caribbean declined by more than 50 percent. Coffee production fell

as well, primarily because of the shortfall resulting from the loss of the

North American market. Figures based on annual reports by the island Naval

Officer to the Jamaica House of Assembly reprinted in the House of

Assembly, Jamaica, Votes of the Honourable Assembly of Jamaica, 45

vols. (Saint Jago de la Vega, Jamaica, 1795–1835) for each year.

For food shortages on the Leeward Islands,

see Richard B. Sheridan, Doctors and Slaves: A Medical and Demographic

History of Slavery in the British West Indies, 1680–1834

(Cambridge, 1985), 156. For those suffering from malnutrition on

Montserrat, see Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided: The

American Revolution and the British Caribbean (Philadelphia, 2000), 160–61.

7 See

Alice B. Keith, "Relaxations in the British Restrictions on the

American Trade with the British West Indies, 1783–1802," Journal

of Modern History 20, no. 1 (March 1948): 1–2; Selwyn H. H.

Carrington, "The United States and the British West Indian Trade, 1783–1807,"

in West Indies Accounts: Essays on the History of the British Caribbean

and the Atlantic Economy, ed. Roderick A. McDonald (Kingston, Jamaica, 1996),

149–51.

8 For

the unsuccessful appeals to Parliament, see "Resolutions of the

Committee of West India Planters and Merchants, Feb. 6, 1784," in

Vincent Harlow and Frederick Madden, eds., British Colonial Documents,

1774–1834 (Oxford, Eng., 1953), 256; O'Shaughnessy, Empire

Divided, 240.

Here is Jamaica's House of Assembly

petition: "We most humbly request that you will be pleased to permit

the importation from the United States of America in American bottoms, of

the articles enumerated in the proclamation of 2nd July last and also to

permit the produce of this Island to be exported in return for the space of

nine months" (Journals, 8, Nov. 19, 1783). Campbell's response appeared

the following day, Nov. 20, 1783. Planters were hardly impressed and formed

a committee to study the effects of declining North American trade on local

productivity. Though the report does not specify the source for its

figures, committee members argued that more than fifteen thousand slaves

had died in Jamaica as the result of starvation and insufficient nutrition,

resulting from recent hurricanes and "the exclusion of American

vessels" (report in Bell, English Historical Review 31: 440 n.

67). Richard Sheridan argues that the effect of British trade embargoes on

slave subsistence is, if anything, underestimated. Long periods of

nonimportation, limited European and British North American supplies, and

wave after wave of devastating hurricanes resulted in extraordinary damage,

not only in Jamaica but also throughout the British Caribbean (see Richard

B. Sheridan, "The Crisis of Slave Subsistence in the British West

Indies during and after the American Revolution," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 33, no. 4 [October

1976], esp. 621–22, 631–32). In February 1783 Parliament

voted to "permit the produce of such British islands as have been

captured by the enemy during the present war to import in neutral bottoms

... for a limited time" (Journals, 8, Feb. 12, 1783).

9The

Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the

Year 1806 (London, 1808), 48: 81–89.

This source includes a comprehensive overview of British reactions to

reductions in restrictions on United States trade.

10 For

the extension of special concessions, see Carrington, "United States

and British West Indian Trade," 158. For the report on the first

Jamaican hurricane, see the (Philadelphia) Pennsylvania Gazette,

July 7, 1784. Here is Dalling's lift on the food and lumber ban: "On

account of the apprehensions of the inhabitants, from the late dreadful

hurricane, the Governor and Council have given permission, for the space of

four months from the date hereof, to vessels of all nations, and all sizes,

to bring in lumber and provisions—but not permitted to carry the

smallest quantity of produce from the island" ("Extract from a

Letter from Jamaica," Aug. 1, 1784; repr., Penn. Gaz., Oct. 6,

1784). Additional accounts of the 1785 hurricane appeared in Penn. Gaz.,

Oct. 12, Oct. 18, 1785. The 1786 hurricane was described in Penn. Gaz.,

June 21, 1786. The article includes a letter written from Elizabeth Town,

Jamaica, which voices some of the island residents' frustrations before the

ban on American imports was again lifted: "Our crops will be but

indifferent this year, principally owing to the last hurricane; we are also

visited with a great drought—the hand of Providence is heavy upon us.

That imp Flowerdew, of the customs, continues the implacable enemy of the

United States, and makes sad havock among your vessels."

11

Richard Henry Lee to James Madison, Nov. 20, 1784, in Robert A. Rutland et al.,

eds., The Papers of James Madison (Chicago, 1973), 8: 145; Benjamin

Harrison to Virginia Delegates, Oct. 3, 1783, ibid., 7: 366; Thomas

Jefferson to Madison, May 8, 1784, in Paul H. Smith et al., eds., Letters

of Delegates to Congress, 1774–1789 (Washington, D.C., 1994), 21:

600; Madison to Lee, July 7, 1785, in James Madison Papers, Series 1:

General Correspondence, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. For higher

duties applied to British goods, see Vernon G. Setser, The Commercial

Reciprocity Policy of the United States, 1774–1829 (Philadelphia,

1937), 62–65; Carrington, "United States and British West Indian

Trade," 150–52. For Congress's standardization, see American

State Papers: Commerce and Navigation, 1: 6.

12 The

stipulations of July 2, 1783, were reinforced on Sept. 5 and Dec. 26, 1783

(see Lowell Ragatz, The Fall of the Planter Class in the British

Caribbean, 1763–1833 [New York, 1928], 180). John Adams to Robert

Livingston, July 16, 1783, in Francis Wharton, ed., The Revolutionary

Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States (Washington, D.C.,

1889), 6: 552.

13 Not

only was Saint Eustatius the first to acknowledge American autonomy, some—like

Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore—believed that the colony actively aided

the American cause by forwarding information about British military

strategy. "The Rebels receive all their information" from the

Caribbean, he cautioned, "it is first sent to the British West India

Islands and from thence to St. Eustatia" (Lord Dunmore to Lord George

Germain, July 31, 1776, in William Bell Clark and William James Morgan,

eds., Naval Documents of the American Revolution [Washington, D.C., 1970],

5: 1313–14. See also O'Shaughnessey, Empire Divided, 214). The

province of Holland voted to support the United States as a sovereign

nation in March 1782; other Dutch provinces soon followed suit.

14 For

trade with West Indian colonies, see John Adams to Robert Livingston, July

30, 1783, in RDC, 6: 618. For Dutch limitations, see "Plan of a Treaty

with Holland," Sept. 4, 1778, ibid., 2: 789–98; J. Adams to

Livingston, July 23, July 31, 1783, ibid., 6: 591–95, 621–24. The

initial draft treaty between the United States and Holland in 1778 did not

include commodity restrictions on imports and exports; these restrictions

were added at Holland's insistence. Holland maintained a monopoly on the

last refining stages for all the sugar cultivated on Dutch Caribbean

islands and considered the increasing number of sugar refineries in North

America—including several in Philadelphia—a threat to Dutch

control of the industry. From 1770 to 1785, Philadelphia opened two sugar

refineries; added to the two operating before the American Revolution,

these represented a significant increase in the city's sugar manufacturing

capabilities. The number of sugar refineries is compared in Constables

Returns for the City of Philadelphia, 1775, Philadelphia City Archives, and

Edmund Hogan, The Prospect of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1795). One

of Philadelphia's earliest published business directories, Prospect of

Philadelphia is available at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Adams