SEDE VACANTE 1691

(February 1, 1691—July 12, 1691)

|

AG scudo VBI • VVLT • SPIRAT [John 3. 8] (in exergue:) ROMA The Holy Spirit, surrounded by rays of light interspersed with tongues of fire. |

|

SEDE • VACANT|E • MDCLXCI |

PALUZZO CARDINAL PALUZZI ALTIERI DEGLI ALBERTONI (1623-1698). Paluzzo Paluzzi was a member of one of Rome's distinguished families.

He obtained a doctorate in law at the University of Perugia. He joined the Apostolic Chamber under Urban VIII Barberini, and became Auditor General

under Alexander VII Chigi. His family was joined with the Altieri when his nephew, Gaspare Albertoni, married the niece and sole heiress of the family

of Emilio Cardinal Altieri. In 1664 he was named Cardinal Priest and received the titulus of SS. Apostoli (which he exchanged for S. Crisogono and then

S. Maria in Trastevere). He was elected Bishop of Montefiascone and Corneto in 1666.

In 1670, his relative Emilio Cardinal Altieri, was elected Pope Clement X, and on the day of the election the new pope adopted Paluzzo Paluzzi

and named him Cardinal Nephew. He received a number of important benefices as a result: Archbishop of Ravenna (1670-1674?),

Legate in Avignon (1670), Legate in Urbino (1673-1677), Governor of Tivoli. He became Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Church on August 4, 1671,

a post which he held until his death on June 29, 1698. In 1691 he was promoted to be Cardinal Bishop of Sabina, then Palestrina, and then to

Porto and Santa Rufina in 1698. He was Archpriest of the Lateran from 1693-1698.

On July 1, 1698, Dom Claude Estionnot, Procurator General of the Benedictines, wrote to Dom Jean Mabillon [P. Valery (ed.), Correspondence inédite de Mabillon et de Montfaucon avec l' Italie III (Paris 1847), no. cccviii, p. 11-12]:

Son Eminence Altieri mourut hier, âgé de soixante-dix-sept ans, partie de vieilesse, partie de chagrin, de ce que son neveu le cardinal Lorenzo, n'ayant pas contenté dans sa légation d'Urbin, et s'etant laissé gouverner par des gens qui faisaient leurs affaires et non pas le bien de la légation, en a été rappelé avec peu de réputation pour lui. Vous voyez par là che ogni uno ha le sue guaiie; il laisse outre le chapeau, le camerlingat, la protection de Lorette, la protection des ordres des Carmes, des Augustins et Dominicains, plusieurs abbayes vacantes et un grand nombre de pensions. Si tant est qu'il ne les ait pas transférées, car on n'en sait encore rien, son testament n'étant pas encore public. Voilà par cette mort son Altesse Eminentissime de Bouillon sous-doyen du sacré collége, avec douze mille livres de rentes plus qu'il n'avait.

He participated in the Conclaves of 1667 and 1669-70 and presided at the Conclaves of 1676, 1689, and 1691.

The Marshal of the Conclave was Prince Giulio Savelli (1626-1712), the second son of Prince Bernardino Savelli, Prince of Albano (1606-1658) and Felice Peretti, the heiress of Pope Sixtus V. He married Caterina Aldobrandini, daughter of Pietro Aldobrandini, Duke of Carpentino, and then Caterina Giustiniani. The family were perpetually in financial difficulties: in 1596 they sold Castel Gandolfo to the pope, and in 1650 the duchy of Albano. He succeeded his father as Marshal of the Holy Roman Church in 1658. He had one son, who predeceased him. On his death in 1712, the office of Marshal of the Roman Church was conferred on the Chigi Family. Prince Giulio Savellio left a manuscript Conclave Diary; it is in the Chigi archives.

The Governor of the Conclave and Governor of the Borgo was Msgr. Giuseppe Paravicino of Milan. He was also Treasurer General S.R.E. He died at the age of 46, on November 28, 1695 [His monument in S. Francesco a Ripa: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma IV, p. 423 no. 1035].

The Conservatori di Roma were: Marchese Fabrizio Nari, Marchese Ottavio Lancellotti, and Marchese Antonio Santacroce [Forcella Inscrizioni I, p. 7 col. 2].

The Governor of Rome was Msgr. Spinola.

The Secretary of the Sacred College of Cardinals was Msgr. Guido Passionei.

The Masters of Ceremonies at the Conclave of 1691 were: Domenico Cappello, Pietro Santi di Fontibus, Candido Cassina, Giustiniano Chiapponi, and Bernardino Porto [ Bullarium Romanum 20, 171]—Capello, Cassina and Porto left Diaries.

Pope Alexander VIII

Relations between France and the Papacy had not been good at the conclusion of the reign of Innocent XI. King Louis XIV took the highly unusual step of having printed a letter which he had sent to his Ambassador in Rome, Cardinal César d'Estrées, who was instructed to read the letter in the presence of the Pope. Written at Versailles on September 6, 1688, [Mention, Documents, pp. 104-112], the letter says in part:

Je m' assure que tous les Princes et Etats de la Chrétienté qui considèront sans passion la conduite que le Pape a tenue envers moy depuis son élévation au Pontificat et qui connoîtront d'ailleurs les soins et les empressements que j'ay toujours eu à rechercher son amitié, tout ce que j'ay fait pour le bein et l'avantage de nostre Religion, mon attachement sincère et ma vénération pour le Saint Siège, mon application à maintenir le repos de l'Europe, sans me prévaloir des conjonctures favorables et de la puissance que Dieu m'a mise en main, s' étonneront plustot que j'aye soufert tant d'injures et de mauvais traitemens de la Cour de Rome et que j'aye laissé en mesme temps agrandir l' Empereur contre toutes les règles d'une bonne politique, que de la juste protection que je suis resolu de donner à des Princes et à un Chapitre [of the Cathedral of Cologne] que le Pape et l' Empereur veulent dépouiller de leurs possessions et de leurs droits, contre toute justice, et seulement à cause qu'ils les croyent reconnaissans des marques qu'ils ont toujours reçues de mon estime et de mon affection.

In the opinion of King Louis, Pope Innocent was partial to the Imperial interest and hostile to France. The French, under the leadership of the Duc de Chaulnes and Cardinal d'Estrées, had worked successfully in 1689 to place a friend of France on the Papal Throne. They believed that they had succeeded, in the person of Pietro Ottoboni of Venice. Before he could be elected, however, Ottoboni and his nephew had to give guarantees to the French that they would work toward a reconciliation between France and the Holy See. But after the coronation, it was a somewhat different matter. Chaulnes, in fact, is accused of working more in the direction of helping the Papacy to defend itself against Louis XIV rather than the reverse [Michaud, 142-143]. Louis decided to replace him as ambassador. Pope Alexander finally gave in on the issue of awarding the red hat to Bishop Forbin Janson, and the new cardinal, whose attitude was completely congruent with King Louis', was sent to Rome to replace Chaulnes. He took up his post in the first week of July, 1690. Forbin Janson's attitude, thoroughly Gallican in spirit, and his general cynicism, is revealed in a private letter to Louis XIV, written on December 28, 1690, two months before the Pope's death [Gérin, 192]:

In the opinion of King Louis, Pope Innocent was partial to the Imperial interest and hostile to France. The French, under the leadership of the Duc de Chaulnes and Cardinal d'Estrées, had worked successfully in 1689 to place a friend of France on the Papal Throne. They believed that they had succeeded, in the person of Pietro Ottoboni of Venice. Before he could be elected, however, Ottoboni and his nephew had to give guarantees to the French that they would work toward a reconciliation between France and the Holy See. But after the coronation, it was a somewhat different matter. Chaulnes, in fact, is accused of working more in the direction of helping the Papacy to defend itself against Louis XIV rather than the reverse [Michaud, 142-143]. Louis decided to replace him as ambassador. Pope Alexander finally gave in on the issue of awarding the red hat to Bishop Forbin Janson, and the new cardinal, whose attitude was completely congruent with King Louis', was sent to Rome to replace Chaulnes. He took up his post in the first week of July, 1690. Forbin Janson's attitude, thoroughly Gallican in spirit, and his general cynicism, is revealed in a private letter to Louis XIV, written on December 28, 1690, two months before the Pope's death [Gérin, 192]:

L’autorité et l’intérêt sont presque les deux seules maximes sur lesquelles roule, toute la politique de cette cour. La religion, la piété et le bien de l'Eglise ne sont quasi que des noms que l‘on a souvent dans la bouche sans en avoir les sentiments dans le cœur; et ces vertus ne seraient guère ici d’aucun usage s’il ne se trouvait pas d’occasion de les faire servir de prétexte, ou en faveur de cette autorité qu'on veut accroitre, ou en faveur de ces intérêts particuliers qu'on veut toujours ménager. Le pape, les cardinaux et les prélats n’ont ordinairement que ces deux vues dans leur conduite. Le premier écoute volontiers les flatteu rs qui lui disent que sa puissance est indépendante et qu’ilpeut .ire tout ce qu’il veut‘, et les autres entrent aussi naturellement dans les mêmes sentiments, soit par l’espérance dont ils se flattent de parvenir un jour au pontificat, soit par la gloire qu’ils trouvent à être ou ministres ou officiers d’un chef et d’un prince dont ils se figurent l`autorité sans bornes et sans limites. L’intérêt n'a pas des motifs moins puissants ..... Voilà en gros le plan de cette cour et les maximes fondamentales qu’on y suit.

Alexander VIII Ottoboni ruled only sixteen months, but he did make gestures toward easing the situation with the French government, attempting to work through back-channels by way of Madame de Maintenon. In this effort he was aided by the Glorious Revolution in England (1688), which brought the Protestant William III of Orange to the English throne, much to the discomfort of Louis XIV. He went so far as to gratify Louis XIV with the grant of a cardinal's hat to Louis' strongest supporter among the French clergy, Toussaint de Forbin Janson (February 13, 1690). The Emperor and the King of Spain immediately complained that none of their prelates had been elevated to the purple. But King Louis was not entirely mollified.

Louis, in a gesture which cost him nothing, returned the papal territories of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissan which he had stolen in 1688 in one of his usual demonstrations of force. But when the Pope stood firm both on the Gallican Articles and the matter of the regalian rights, and drew up a constitution Inter Multiplices (August 4, 1690) nullifying both actions of Louis XIV, all hopes seemed to have collapsed. The bull was not published, however, until the Pope was on his death bed. On October 16, on the day that Alexander canonized several saints, it was noticed that he seemed to be suffering from a sudden weakness (a stroke, perhaps). The doctors who were treating the pope saw no chance of recovery and suggested that he should put his affairs in order. The Pope, however, continued to live on. The papal obstinacy toward France continued as well; it was repeated on the day before the Pope's death, when he summoned the Cardinals to a Consistory and issued another Bull, Quandoquidem, repeating all of the censures of the Gallican Articles. King Louis forbade the publication of the Bulls in France, and threatened to appeal the Bull to a General Council [Petruccelli III, p. 363]. Since it had been known even in August that the Pope was ill (he was eighty years old), there was sufficient time for the French to mount a major campaign to get a pope who would reverse these decisions. The Duc de Chaulnes and Cardinal Forbin Janson were hard at work. The problem, however, would turn out to be the lack of unity of goal or of methods on the part of the French cardinals.

Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri had approached the King and offered a number of committments to resolve the issues which separated France and the Papacy; he was supported by Cardinal d'Estrées. But Cardinal d'Estrées had his competitors at court: Lavardin, Cardinal Bonzi (Archbishop of Narbonne), and Cardinal Forbin Janson (Archbishop of Beauvais), who immediately opposed Altieri. D'Estrées also supported Cardinal Carpegna, but Louis remembered the part he had played in the excommunication of Levardin and rejected him. Lauria was acceptable, as was Delfino. But d'Estrées took note of Delfino's friendship with Cardinal Chigi. D'Estrées also put forward the names of Ginetti (Bishop of Fermo) and Conti di Poli (the 74 year-old Bishop of Ancona). But Choisy poined out that Conti had friendly relations with Austria. Choisy himself was working for Buonvisi, and this proposal had the approval of d'Estrées, but Lavardin hated him and labelled him an Imperialist. Acciaioli was dismissed by d'Estrées as too severe, despite the fact that he was the favorite of the Duc de Chaulnes and Cardinal de Bouillon. Cardinal De Angelis, who was eighty, was the choice of the ladies of the Court, but d'Estrées had no great opinion of him. D'Estrées, de Furstenburg, and Lavardin could agree on Cardinal Spinola (who was 79 and ill), though Forbin Janson deprecated him as being too close to Spain. Père Lachaise, the King's confessor, thought that the pope should be one of the Romans. Finally, d'Estrées included Barbarigo in his list. Nobody, it seems, had any interest in Cardinal Pignatelli. In the end no agreement was reached, beyond the decision that French votes would not go to any candidate unless he agreed to promote the program set forth by King Louis [Petruccelli III, pp. 363-365]. This was not a position of any strength or purpose, but of indecision.

Death of the Pope

On January 20, 1691, Cardinal Forbin Janson informed King Louis XIV that Pope Alexander was seriously ill, and on the 22nd that his condition was perilous and that his nephew, Cardinal Ottoboni, had little hope. On the 27th, he reported that gangrene had set in, and that the Duc de Chaulnes was trying to have the Conclave organized and a pope chosen before the French cardinals could arrive [Gérin, 200]. On January 30, the dying Pope summoned the twelve Cardinals whom he had created who were in Rome to his bedside, and in the presence of two Protonotaries Apostolic, who were making an official record of the proceedings, made a statement [Gérin, 202, quoting a letter of Forbin Janson, who arrived late and did not attend the meeting, to Louis XIV]:

il avait considéré qu’il n’avait été élevé à la suprême dignité qu’il possédait que parce qu`il avait été le fidèle conseiller de son prédécesseur, et qu’il l’avait toujours affermi et encouragé a la défense des droits du Salnt·Siége dans les contestations qu’il avait eues avec la France; qu`il savait bien que le Sacré Collége avait attendu de lui‘qu’iI pratiquerait les conseils qu’il avait donnés, qu’il maintiendrait ce qu'Innocent XI avait fait et qu’il défendrait les memes droits avec le même zèle; qu`à la vérité il avait voulu accommoder ces différends, mais que c’était avec tout l' avantage du au Saint-Siège, en obligeant les évéques de France à rétracter tout ce qui avait été fait dans leur assemblée; mais que, n’ayant pu l’obtenir, il croyait être obligé de donner au Sacré Collège la satisfaction qu'il attendait de lui et de rendre public un bref qui avait été projeté dans le temps d'Innocent XI et examiné plusieurs fois dans les congrégations des cardinaux , et que, pour cet effet, il ordonnait qu’en leur en fit la lecture.

This was the publicatio of the Constitution Inter multiplices, which annulled the Gallican Articles and the extension of the regalia by Louis XIV [Bulliarum Romanum Turin edition 20, pp. 67-70 (signed on August 4, 1690)]. It was affirmed by the Constitution Quandoquidem.

The plague had been raging in Naples, and despite precautions taken against it, it appeared in Rome, and the Pope was infected [Relazione dell' ultima Infermità, p. 1]. Alexander VIII died on February 1, 1691 at around 4:00 p.m. (22 hours, Roman Time) [Bischofshausen, 171-173]. His passing was assisted by Cardinal Colleredo, the Major Penitentiary, the Father General of the Dominicans, the Procruator General of the Jesuits, the Father General of the Carmelites Scalzi della Scala, the Penitentiaries of S. Peter's, and of Father Marchese of the Oratorians. The ceremony of the recognition was performed by the Cardinal Camerlengo, Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri degli Albertoni and the Clerics of the Chamber, assisted by the Masters of Ceremonies Pietro Santi and Domenico Capello (no mention being made in the Relazione dell' ultima Infermità of a tapping silver hammer or of the calling of the baptismal name of the Deceased) . The ring of the Fisherman was surrendered by Msgr. Draghi-Bertoli. The Camerlengo then proceeded to the Capitol to announce the death of the Pope to the Senate and People of Rome. The body of the late Pope was opened on February 2, 1691, by Signore Ipolito Magnani, surgeon of the Apostolic Palace; the praecordia were removed, and the corpse was enbalmed in the customary fashion. The report of the autopsy is preserved in the manuscript Vaticanus Latinus 8229 [Vincenzo Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 187, no.584]

On February 2, the body of the Pope was placed on view in one of the chambers of the Quirinal Palace; that evening it was transferred to the Vatican, to the sound of the bells of the churches and the cannon from Castel S. Angelo, and placed in the Sistine Chapel, where it was revested in pontifical vestments. It was then transferred to the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in the Vatican Basilica, where it lay in state for three days. In the evening of February 5, Alexander VIII was buried in the presence of his nephews and the Cardinals whom he had elevated to the Purple.

Official letters from the College of Cardinals, dated February 2, 1691 (though probably sent a short time later), notified the various princes of Europe of the death of Pope Alexander VIII [Codex Ottobonianus 730: V. Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma II (Roma 1880), p. 25, no. 47].

The Cardinals

A list of participants is given in the contemporary pamphlet, Conclave fatto per la Sede Vacante d' Alessandro VIII, nel quale fù creato Pontefice il Cardinale Antonio Pignatelli Napolitano, detto Innocentio XII alli 12. di Luglio 1691, pp. 39-47. Another and better list can be found in Guarnacci I, columns 401-404. Two official lists can be found in the Bullarium Romanum (Turin edition) Volume 20, pp. 169-175. There was a total of seventy living Cardinals. Five did not attend. Four left the Conclave and did not vote in the final ballot. Two of those four had died (Capizucchi and Spinola).

- Alderano Cibò (aged 78) [Genoa], of the family of the Principi di Massa di Carrara, Bishop of Ostia and Velletri [Cappelletti, Chiese d' Italia I (Venezia 1844), 479-480, 487], Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. (died July 22, 1700)

- Flavio Chigi (aged 60) [Siena], Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (1689–1693). Prefect of the Signature of Justice (died September 13, 1693). Nephew of Pope Alexander VII. Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica.

- Giacomo Franzoni (aged 79) [of Genoa], Bishop of Frascati (1687–1693) [Cappelletti, Chiese d' Italia I (Venezia 1844), 644, 651]. Later Bishop of Porto (1693-1697). (died December 19, 1697).

- Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri degli Albertoni (aged 68) [Romanus], Bishop of Sabina, Prefect of the S.C. de Propaganda Fide. Doctorate in law (Perugia). Camerlengo

- Emmanuel de la Tour d'Auvergne de Bouillon (aged 48) [France], Bishop of Albano (1689-1698). Succeeded Cardinal Cibò as Bishop of Ostia in 1700 [Cappelletti, Chiese d' Italia I (Venezia 1844), 480-481, 487]. Formerly Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (died March 2, 1715). His conclavist was again Abbe Melchior de Polignac.

- Francesco Maidalchini (aged 70) [of Viterbo], nephew of Olimpia Maidalchini, wife of Innocent X's brother. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Via (1689-1691). (died June, 1700). [At the Conclave of 1676 he had been Cardinal Protodeacon]

- Carlo Barberini (aged 61) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Lucina (1685-1704). (died October 2, 1704). Grand-nephew of Urban VIII. Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica (1667-1704). Representative of the Kings of Portugal and of Poland.

- Gregorio Barbarigo (aged 66) [Venice], Cardinal Priest of S. Marco (died June 18, 1697). Bishop of Padua (1664-1697). Doctor in utroque iure (Padua).

- Giannicolò Conti di Poli (aged 74) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria Traspontinae (1666-1691) (died January 20, 1698) Bishop of Ancona.

- † Giulio Spinola.(aged 79) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of San Martino ai Monti [left the Conclave on February 21, 1691, due to illness; died March 11, 1691, during the Sede Vacante]. Bishop of Nepi and Sutri.

- Giovanni Delfino (aged 74) [Venice], Cardinal Priest of SS. Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (died July 19, 1699). Patriarch of Aquileia. Senator of Venice at the age of 30 [Eggs, Purpura Docta VI, 489-490; Cardella 7, 181-182]

- Niccolò Acciaioli (aged 61) [Florence], Cardinal Priest of S. Callisto (1689–1693) (died February 23, 1719) Doctorate in Law (Rome)

- Gasparo Carpegna (aged 66) [Romanus], Cardinal-Priest of S. Maria in Trastevere (1689–1698) Subsequently Bishop of Sabina (died April 6, 1714). Vicar General of Rome

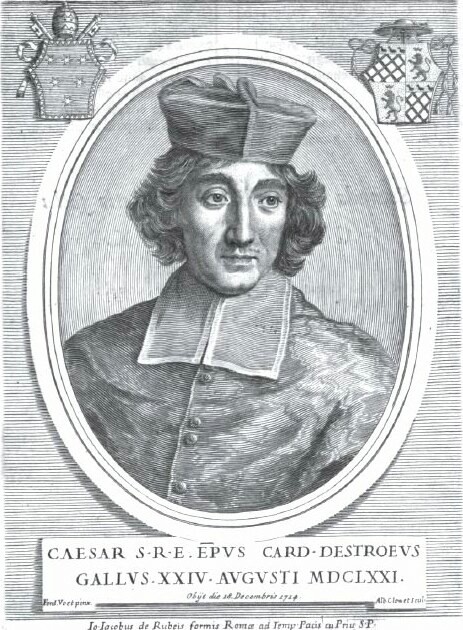

- César d'Estrées (aged 60) [France] Cardinal Priest of Santissima Trinità al Monte Pincio (1675–1698). Subsequently Bishop of Albano (died December 18, 1714). Former Bishop of Laon .

- Pierre de Bonzi (aged 61) [Florence], son of Conte Francesco Bonzi, senator of Florence, who was attached to Marie de Medicis; and Christina Riario. Conte Francesco was Resident of the French King in Mantua. Pierre's uncle Clement was made Bishop of Beziers (1632-1659) through Queen Marie's influence [Gallia christiana 6, 375-376]. In 1659 he succeeded his uncle as Bishop of Beziers (1659-1671) [Gallia christiana 6, 376]. Grand Duke Ferdinand II of Tuscany made Pierre resident agent at the French court, where he arranged the marriage of Marguerite Louise, daughter of Gaston, Duke of Orleans, and Cosimo III (1661). In 1662 he was sent by the King of France as ambassador to Venice. In 1665 Louis XIV, satisfied with his work, appointed him Ambassador to Poland. He returned in 1669, and was made Ambassador Extraordinary to Spain. Bishop of Toulouse (1671-1673). Archbishop of Narbonne (1673-1703) [Gallia christiana 6, 123; Michaud, Louis XIV et Innocent XI III, 139-147].(1672–1701) Archbishop of Narbonne (died July 11, 1703). Cardinal Priest of S. Eusebio (1689–1703).

- Vincenzo Maria Orsini de Gravina, O.P. (aged 42) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (died February 21, 1730). Archbishop of Benevento (1686-1730). Subsequently Bishop of Frascati, then Porto, and then Rome.

- Federico Baldeschi Colonna (aged 65) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia (1685–1691) (died October 4,1691) [Left the Conclave on June 29]

- Francesco Nerli (aged 55) [Florentinus], son of Pietro Nerli and Costanza Magalotti. Cardinal-Priest of S. Matteo in Merulana (1673-1704). He had studied philosophy in Rome, and Civil and Canon Law in Siena, and received his Doctorate in Pisa. In 1638 Alexander VII made him a Referendary and one of the Abbreviatores de parco maiori in the Apostolic Camera. In 1666 he was named vice-Legate in Bologna. Clement IX made him a voting member of the Apostolic Segnatura. Clement X made him a Canon of the Vatican Basilica. Archbishop of Florence (1670-1682), and Nuncio to Vienna and Poland. Nuncio in France (1672-1673). He was named cardinal on June 13, 1673, and presented with the red biretta by Maria Theresia. Secretary of State (1673-1676). Bishop of Assisi (1685-1689). [Guarnacci I, column 52]. He was made Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica and Prefect of the SC RR. Fabrica by Clement XI (1704-1708). He died on April 8, 1708, at the age of 72, having been a cardinal for thirty years. His funeral inscription is in S. Matteo in Merulana [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma 10, p. 455 no. 739]

- Galeazzo Marescotti (aged 63) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of SS. Quirico e Giulitta (1681–1700). Former diplomat to the Spanish Court. Former Bishop of Tivoli (died July 3, 1726). Doctor in utroque iure. [Guarnacci I, 73-76; Cardella 7, 230-231].

- Girolamo Casanate (aged 71) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of of S. Silvestro in Capite (1689–1700), previously of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1686–1689). Doctor in utroque iure (Naples); he practiced as a lawyer. He became the protegé of Giovanni Battista Cardinal Pamfilj, who had been Nuncio to the Court of Naples from 1621-1625, and who convinced Girolamo's father, during a diplomatic visit to Rome, to allow his son to take up the ecclesiastical profession. When Pamfilj became Pope Innocent X in 1644, Casanate was named Chamberlain of Honor. He was appointed Governor of Sabina, then Governor of Fabriano and Camerino. Under Alexander VII he was governor of Ancona. From 1658 to 1662 he was Inquisitor at Malta. He was Governor of the Conclave after the death of Alexander VII (1667). On June 12, 1673, he was created Cardinal deacon by Clement X on June 12, 1673, who also appointed Casanate Assessor at the Holy Office. Clement XI appointed him Secretary of the SC of Bishops and Regulars. Innocent XII named him S.R.E. Bibliothecarius after the death of Cardinal Lorenzo Brancati [Lauria] (December 1, 1693). Cardinal Casanate died on March 3, 1700, at the age of 80, and was buried in the Lateran Basilica [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma 8, p. 72 no. 194]. In his Will, he left his personal library of more than 23,000 volumes to found the Biblioteca Casanatense at the Minerva, along with an endowment of 80,000 gold scudi [Pietro Ercole Visconti, Città e famiglie nobili e celebri dello Stato Pontificio II (Roma 1847), p. 5].

- Fabrizio Spada (aged 48) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono (1689–1708). Subsequently Bishop of Palestrina (died June 15, 1717). Doctor in utroque iure (Perugia).

Philip Thomas Howard of Norfolk and Arundel, OP (aged 61) [born September 21, 1629, at Arundel House, London, England], third son of Henry Frederick Howard, third Earl of Arundel, and Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of Esme, Lord d'Aubigny (later Duke of Richmond and Lennox). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1679–1694). He and his brothers studied briefly at Cambridge, then at Utrecht and Antwerp. Having fled from England on the announcement of his Catholic belief, he became a Cavalry officer for the Duke of Savoy. Desiring a quiet life, however, in 1645 he became a Dominican novice at Cremona. His relatives, the Duke of Savoy, the Cardinal Archbishop of Milan and other cardinals of the Papal Court attempted to reverse his decision—but without success. The Pope then referred his case to the cardinals at the SC de propaganda fide, and summoned Howard to Rome to undergo his novitiate. He spent five months with the Oratorians, where the truth of his vocation was tested. The Pope, satisfied, gave the Vicar General of the Dominicans, Domenico Marini, permission to admit Howard to solemn profession in the Order at the Convent of S. Sisto. He was 17. He continued his studies in Naples, at the Convent of S. Maria della salute, and then at Rennes in Brittany. He was ordained priest at the age of 22, thanks to a papal dispensation. He founded a monastery in honor of the Virgin Mary at Bornheim in East Flanders, and was appointed the first Prior on December 15, 1657. When the monarchy was restored in England he was summoned home to negotiate the marriage of King Charles and Catherine of Braganza, whose Almoner he became. He was also her Chaplain and in charge of her Oratory. He lived at St. James' Palace, where he dined with Samuel Pepys (Diary III, 47-49). The Pope, badly advised by the enthusiasts at the Propaganda, who insisted that England was eager to return to the Roman obedience, made Howard his Vicar Apostolic in England and titular Bishop of Helenopolis. At the request of King Charles II, however, who knew much better than the Propaganda what the actual feeling of Englishmen was, the bulls were never published and Howard was never consecrated. Protestants, however, were aroused anyway. In 1674, the violence of anti-Catholic feeling in England caused him to flee to Bruxelles. When he had to travel to France to confer with his Father General, he learned that the Pope had appointed him a cardinal (on May 27, 1675). In Rome, he took up residence in the Monastery at Santa Sabina. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore) (1688-1694). Protector of Great Britain (until Innocent XI was persuaded by the Jesuits, who were far more eager than the Cardinal to reconquer England for the Church, to remove Howard). He died on June 17, 1694, and was buried at the Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 505, no. 1946 and 1947]. See the Dictionary of National Biography 28 (London 1891) 54-57 [by Thompson Cooper; Isaacson's biography in The Story of the English Cardinals is nothing but a crib of the DNB article].

Philip Thomas Howard of Norfolk and Arundel, OP (aged 61) [born September 21, 1629, at Arundel House, London, England], third son of Henry Frederick Howard, third Earl of Arundel, and Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of Esme, Lord d'Aubigny (later Duke of Richmond and Lennox). Cardinal Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1679–1694). He and his brothers studied briefly at Cambridge, then at Utrecht and Antwerp. Having fled from England on the announcement of his Catholic belief, he became a Cavalry officer for the Duke of Savoy. Desiring a quiet life, however, in 1645 he became a Dominican novice at Cremona. His relatives, the Duke of Savoy, the Cardinal Archbishop of Milan and other cardinals of the Papal Court attempted to reverse his decision—but without success. The Pope then referred his case to the cardinals at the SC de propaganda fide, and summoned Howard to Rome to undergo his novitiate. He spent five months with the Oratorians, where the truth of his vocation was tested. The Pope, satisfied, gave the Vicar General of the Dominicans, Domenico Marini, permission to admit Howard to solemn profession in the Order at the Convent of S. Sisto. He was 17. He continued his studies in Naples, at the Convent of S. Maria della salute, and then at Rennes in Brittany. He was ordained priest at the age of 22, thanks to a papal dispensation. He founded a monastery in honor of the Virgin Mary at Bornheim in East Flanders, and was appointed the first Prior on December 15, 1657. When the monarchy was restored in England he was summoned home to negotiate the marriage of King Charles and Catherine of Braganza, whose Almoner he became. He was also her Chaplain and in charge of her Oratory. He lived at St. James' Palace, where he dined with Samuel Pepys (Diary III, 47-49). The Pope, badly advised by the enthusiasts at the Propaganda, who insisted that England was eager to return to the Roman obedience, made Howard his Vicar Apostolic in England and titular Bishop of Helenopolis. At the request of King Charles II, however, who knew much better than the Propaganda what the actual feeling of Englishmen was, the bulls were never published and Howard was never consecrated. Protestants, however, were aroused anyway. In 1674, the violence of anti-Catholic feeling in England caused him to flee to Bruxelles. When he had to travel to France to confer with his Father General, he learned that the Pope had appointed him a cardinal (on May 27, 1675). In Rome, he took up residence in the Monastery at Santa Sabina. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore) (1688-1694). Protector of Great Britain (until Innocent XI was persuaded by the Jesuits, who were far more eager than the Cardinal to reconquer England for the Church, to remove Howard). He died on June 17, 1694, and was buried at the Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 505, no. 1946 and 1947]. See the Dictionary of National Biography 28 (London 1891) 54-57 [by Thompson Cooper; Isaacson's biography in The Story of the English Cardinals is nothing but a crib of the DNB article]. - Giovanni Battista Spinola (aged 78) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Cecilia (1681–1696). Former Archbishop of Genoa (1664-1681). Doctor in utroque iure.

- Antonio Pignatelli del Rastrello (aged 76) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of S. Pancrazio (1681–1691). Maestro di Camera of Innocent XI. Archbishop of Naples (1687-1691). Bishop of Faenza (1682-1687). Doctor in utroque iure (Rome)

- Francesco Buonvisi (aged 62) [Lucca], Cardinal Priest of S. Stefano al Monte Celio (1689–1700). Bishop of Lucca (September 7, 1690-August 25, 1700). Doctor in utroque iure (Rome, Sapienza)

- Savo Millini (aged 47) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Vincoli (1689–1701) Bishop of Orvieto (1681-1694). (died February 10, 1701). Doctor in utroque iure (Rome, Sapienza)

- Federico Visconti (aged 74) [Milan], Priest of SS. Bonifacio ed Alessio (1681–1693). Archbishop of Milan (1681-1693). Doctor in utroque iure (Pavia)

- † Raimondo Capizucchi, OP (aged 76) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Maria degli Angeli (1687–1691). formerly Magister Sacri Palatii Apostolici (1673-1681) [Catalano, 178-182]. He left the conclave because of illness on April 13, 1691 and died on April 22, 1691, during the Sede Vacante. His praecordia were buried at the Minerva [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma I, p. 505 no. 1944].

- Francesco Lorenzo Brancati di Lauria, OFM Conv. (aged 79), Cardinal Priest of Ss. XII Apostoli (1681–1693). (died November 30, 1693). S.R.E. Bibliothecarius. Professor of philosophy, lecturer in Theology.

- Giacomo de Angelis (aged 80) [Pisa]. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria in Ara Coeli (1686–1695). He was Abbot Commendatory of the Abbey of Nonantola (1687-1695). (died September 15, 1695) Doctor in utroque iure (Pisa)

- Opizio Pallavicino (aged 59) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Martino ai Monti (1689–1700). (Died February 11, 1700). Bishop of Spoleto. Doctor in utroque iure.

- Marcello Durazzo (aged 56) [Genoa], Cardinal Priest of S. Prisca (1689.11.14 – 1701.02.21). (died April 27, 1710). Bishop of Ferrara. Doctor in utroque iure (Perugia).

- Marcantonio Barbarigo (aged 51) [Venice], Cardinal Priest of S. Susanna (1686–1697). Bishop of Montefiascone e Corneto (1687-1706). Archbishop of Corfu (1682-1686). Doctor in utroque iure (Padua). (died May 26, 1706)

- Carlo Stefano Ciceri (aged 74) [Como], Cardinal Priest of S. Agostino (1687–1694). (died June 24, 1694). Bishop of Como. Doctor in utroque iure (Bologna).

- Leopold Karl von Kollonitz (Lipot Kollonics) (aged 60 [German], Cardinal Priest of S. Girolamo dei Schiavoni/Croati (1689–1707). (died January 20, 1707). Bishop of Györ.

- Etienne Le Camus (aged 51) [France], Cardinal Priest of S. Pietro in Montorio (1689–1696). (died October 19, 1696). Bishop of Grenoble, France. Doctor of Theology (Sorbonne)

- Johannes von Goes [Goessen, Goëss] (aged 79) [Bruxelles, Flandre], Cardinal Priest (1686) of S. Pietro in Montorio (1689-1696), Bishop of Gurk. (died October 19, 1696, at the age of 85). Sacri Romani Imperii Princeps. Advisor of Emperor Leopold I of Austria. [His inscription in SS. Concezione: V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiesa di Roma IV, p. 212 no.534].

- Pier Matteo Petrucci, Orat. (aged 54) [Jesi] Cardinal Priest of S. Marcello (died July 5, 1701). Doctor in utroque iure (Macerata).

- Pedro de Salazar (aged 61) [Spain], Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1689-1706). (died August 15, 1706). Bishop of Córdoba

- Jan Casimir Dönhoff (aged 42) [Poland], Priest of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina (1686–1697) (died June 20, 1697). Bishop of Cesena.

- José Sáenz de Aguirre, OSB (aged 61) [Spanish], Cardinal Priest of S. Balbina (1687–1694) (died August 19, 1699). (Giuseppe d'Aghirro) (aged 61) [Spain] Doctor of Theology (Salamanca).

- Leandro di Colloredo, Orat. (aged 52) [Friuli], Cardinal Priest of SS. Nereo ed Achilleo (1689-1705). (died January 11, 1709). Maior Penitentiarius. [Guarnacci I, columns 269-272; Cardella 7, 290-295]. [Cardinal Goëss, in a letter to the Emperor Leopold I, counts Colloredo as a Venetian: Wahrmund, p. 288]

- Fortunato Caraffa della Spina (aged 60) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1687–1697). (died January 16, 1697). Bishop of Aversa.

- Bandino Panciatici (aged 62) [Florence], Cardinal Priest of S. Tommaso in Parione (1690–1691). (died April 21, 1718). Relative of Clement IX. Pro-Datary of Alexander VIII and of Innocent XI. Doctor in law, Pisa.

- Giacomo Cantelmo (aged 45) [Naples], Cardinal Priest of Ss. Marcellino e Pietro (1690–1702). (died December 11, 1702). Archbishop of Capua.

- Ferdinando d'Adda (aged 41) [Milan], Cardinal Priest of S. Clemente (1690–1696). (died January 27, 1719)

- Toussaint de Forbin Janson (aged 40) [France], Cardinal Priest of S. Agnese fuori le mura (1690–1693). (died March 24, 1713). Bishop of Beauvais (1679-1713), he was an intimate of Louis XIV. He had been one of the bishops who supported the Four Articles at the Assemby of the Clergy in France in 1682. He had been French Ambassador in Poland, and had intrigued to have the Turks invade central Europe. French Ambassador to the Court of Rome, replacing the Duc de Chaulnes. He was appointed to the SC of the Council and the SC of Bishops and Regulars, where he immediately began to intrigue against the Imperialists [Gérin, Revue des questions historiques 22 (1877) 183-186].

- Giovanni Battista Rubini (aged 49) [Venice], Cardinal Priest of S. Lorenzo in Panisperna (1690–1706). (died February 17, 1707) Bishop of Vicenza and Legate in Urbino. Nephew of Alexander VIII. Secretary of State of Alexander VIII [Michaud, p. 80, n.1].

- Francesco del Giudice (aged 55) [Neapolitanus, of Genoese origin], son of Nicolas, Prince of Cellamare and Duke of Giovennazo. Cardinal Priest of S. Maria del Popolo (1690–1700). He came to Rome in the reign of Clement IX, and was made Protonotary Apostolic participantium. Under Clement X, he was made pro-Legate of Bologna, then Governor of Fano. He then became Cleric of the Apostolic Camera, and was promoted under Innocent XI to the post of Praefectus Annonae in the Apostolic Camera. With the patronage of the Marquis of Cocogliudo (Duke of Medina Celi), he was created cardinal by Alexander VIII on February 13, 1690, with the title of S. Maria del Popolo. When Innocent XII became pope, del Giudice did not received expected favors, and so he left Rome for Spain, where he became first Minister of Philip V and Grand Inquisitor (1712). (died October 10, 1725).

- Giovanni Battista Costaguti (aged 55) [Romanus], Cardinal Priest of S. Bernardo alle Terme (1690–1691). (died March 8, 1704).

- Urbano Sacchetti (aged 51) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata (1689–1693). Primus diaconus. Bishop of Viterbo and Toscanella (1683-1699). (died April 6, 1705).

- Gianfrancesco Ginetti (aged 65) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere (1689–1691). (died September 18, 1691) Archbishop of Fermo.

- Benedetto Pamphili, O.S.Io.Hieros. (aged 38) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Agata alla Suburra (1688–1693) (died March 22, 1730). Legate in Bologna.

- Domenico Maria Corsi (aged 53 or 58) [Florence], (died November 6, 1697). Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio (1686-1696). Bishop of Rimini, Legate in Romandiola.

- Giovanni Francesco Negroni (aged 62) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Cesareo in Palatio (1686–1696). (died January 1, 1713). Bishop of Faenza.

- Fulvio Astalli (aged 36) [Romanus]. Cardinal Deacon of SS. Cosma e Damiano (died January 14, 1721) Nephew of Cardinal Francesco Maidalchini.

- Francesco Maria de' Medici (aged 31) [Florence], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Domnica (died February 3, 1711). Brother of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who was married to an Austrian Archduchess. Protector of Austria (Conjectures politiques, 49). Representative of the King of Spain

- Rinaldo d'Este (aged 36) [Modena]. Son of Duke Francesco I and Lucrezia Barberini; his sister Mary of Modena was married to King James II, ex-king of England. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria della Scala (1688-1695). He resigned from the Cardinalate in 1695 in order to procreate another d'Este, which he succeeded in doing. He died in 1737.

- Pietro Ottoboni (aged 23) [Venice], Cardinal Deacon of S. Lorenzo in Damaso pro illa vice Deaconry (1689–1724) (died February 29, 1740) Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church (1689-1740) and Legate in Avignon. Protector of France. Grand-nephew of Alexander VIII.

- Carlo Bichi (aged 53) {Siena], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Cosmedin (1690–1693) (died November 7, 1718). Former Auditor of the Apostolic Camera.

- Giuseppe Renato Imperiali (aged 40) [Genoa], Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro (1690-1726). (died January 15, 1737). Legate in Ferrara.

- Luigi Omodei (aged 35) [Milan], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Portico (1690-1706). (died August 18, 1706).

- Giovanni Francesco Albani (aged 42) [Urbino], Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano al Foro (1690–1700). Secretary of Briefs for Alexander VIII. Subsequently Bishop of Rome.

- Francesco Barberini (aged 29) [Romanus], Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria (1690-1715). (died August 17, 1738). Great-grandnephew of Pope Urban VIII. Nephew of Cardinal Carlo Barberini. Cousin of Cardinal Rinaldo d'Este. Francesco Barberini's brother, Urbano, married Pope Alexander VIII's niece, Cornelia.

- Lorenzo Altieri (aged 29), son of Gaspare Paluzzo Albertoni, Prefect General S.R.E., who was adopted by Clement X (Altieri); his mother was Laura Catherina Aliteri, niece of Clement X. He was also related through marriage to Alexander VIII. Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Aquiro, created on November 13, 1690, at the age of 19. His uncle Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri took him in hand. But he was nonetheless a disappointment, being sacked from his governorship of Urbino in 1698. He died on August 3, 1741, at the age of 70, and was buried in S. Maria in Porticu [V. Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese di Roma V, p. 382, no. 1048].

- † Antonio Bichi (aged 53), Cardinal Priest of San Agostino (died February 21, 1691, during the Sede Vacante) Bishop of Osimo.

- Ludovicus (Luis) de Portocarrero (aged 57), Cardinal-Priest of S. Sabina (1670–1698) Later Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (died September 14, 1709) Archbishop of Toledo. Spanish Minister of State.

- Verissimo de Alencastro [Lencastre] (aged 75) [Lisbon, Portugal]. Cardinal Priest without titulus. (died December 12, 1692). Doctor in utroque iure (Coimbra). Inquisitor General of Portugal and the Azores (1679-1692).

- Augustyn Michal Stefan Radziejowski (aged 45), Cardinal Priest of S. Maria della Pace (1689–1705). (died October 11, 1705). Archbishop of Gniezno. Nephew of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland. Regent of Poland 1703-1704.

- Wilhelm Egon von Fürstenberg (aged 61), Cardinal Priest of S. Onofrio (1689-1704). (died April 10, 1704). Former Bishop of Strasbourg [Afraid of being captured by Imperial troops, he had obtained permission from Louis XIV to remain in France].

Cardinal Colloredo Cardinal Brancati Cardinal d' Estrées

Novendiales

The observation of mourning for the deceased pope (Novendiales) began on February 3. Also the first Congregation of the Cardinals took place on February 3, in the Vatican in the Sala del Papagallo. Msgr. Paravicino, Clerk of the Apostolic Chamber, was elected Governor of the Conclave and Governor of the Borgo. Cardinal Spinola was confirmed as Governor of Rome. Don Antonio Ottoboni was confirmed in his position as General of the Church, and Don Marco Ottoboni as General of the Galleys.

The last day of the Novendiales was February 11.

The Conclave

The Conclave of 1691 began on February 12 [Cardinal Goëss' letter of February 17 to the Emperor], with forty-three cardinals in attendance, and lasted a stormy five months, made all the worse near the end by the heat of a Roman summer and riots in the streets of Rome. Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri said the Mass of the Holy Spirit The Conclave was finally enclosed around midnight by Prince Savelli, in his capacity as Hereditary Custodian of the Conclave. The only French Cardinal present in Rome at the moment was Toussaint de Forbin Janson, the French Ambassador to the Court of Rome (1690-1697). It was essential for Forbin Janson to drag out matters until the French Cardinals arrived. They had set out on the road on February 17, as soon as they had received word that the Pope was dead; they were fully instructed and financed by Louis XIV [Petruccelli III, 365-366]. When the Conclave began, a total of twenty-nine votes was needed for a successful canonical election. As more cardinals arrived, the number increased, until, at the end, it took a minimum of 41 votes to elect a pope.

On February 13 the Cardinals had the papal bulls related to conclaves read to them, and Cardinal Alderano Cibo gave the traditional sermon, calling on the Cardinals to observe all of the rules and regulations of the Conclave. Thereupon the Cardinals and Conclavists took their required oaths. Later on the same day Cardinals Giulio Spinola and Francesco Nerli (who had been indisposed on the previous day) entered conclave. On February 16, Cardinal Federico Colonna, who was suffering from a fever, was forced to leave the Conclave. He later returned, but left again on June 29, and died on October 4. The Neapolitan cardinals were late in entering, since they were under quarantine at the border, due to an outbreak of some contagion (cholera, no doubt) in Naples.

Cardinal del Giudici, who was an open agent of the Spanish King Charles II, did not arrive until March 7, though he was accompanied to the Conclave by Don Luis Francisco de la Cerda ed Aragon, the Marquis de Cocolludo (Duke of Medinaceli on the death of his father on February 20) and a number of Spanish horsemen. Cocolludo was the son of Catalina of Aragon.

The oft-repeated dietary regulations of Gregory X were, as usual, ignored by the more luxuriusly inclined cardinals, Medici, d'Este, Panfilio and Ottoboni. This scandalized some of the Zelanti. Likewise the regulations having to do with security and non-communication with the outside. Numerous documentary references indicate that there was free communication between the Cardinals and the agents of the Crowns.

The Zelanti, some fourteen in number [Petruccelli III, 383], were led by Cardinals Giovanni Francesco Negroni and Leandro Colloredo, who organized the group in an agreement not to proceed to an election unless and until the Sacred College agreed to abandon all nepotism, and to consider no candidate in any terms but merit. Some also wished the Cardinals to agree that whichever of them became the next Pope, he would prohibit nepotism. Innocent XI had tried for years to get the Cardinals to agree to a bull to that effect, but had been unsuccessful. But the Zelanti were not deterred by the impossibility of their demands. Neither were they as united as might seem. Their numbers seemed to grow or decrease as other factors (national loyalty, personal committments, and the individual under consideration); sometimes they were as few as 14 or 15, sometimes they attracted a considerably larger number. At the age of eighteen Colloredo had entered the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, and around the age of thirty he was assigned the duty of preaching. His simplicity, directness, and focus on Christian doctrine brought him to the attention of several cardinals and eventually of Pope Innocent XI (1676-1689). Under his patronage, Colloredo was taken into papal service and eventually promoted to the Cardinalate. As a serious reformer, however, he had chosen to support the saintly Cardinal Gregory Barbarigo, Bishop of Parma [Petruccelli III, p. 387; Wahrmund, 169]. As to the pair, Cardinal Goëss remarked to the Emperor, uterque Venetus, uterque notae virtutis et sanctitatis, villen will frembt vorkomben, das post Papatum Alexandri VIII Veneti noch de Veneta successione gedacht werde.

The French Ambassador (the Duc de Chaulnes) and the Ambassador of Emperor Leopold I (the Prince de Lichtenstein) were at odds, as were important members of their suites (especially the Duke of Medinaceli) with each other. Even in Vienna the Emperor Leopold had been receiving contradictory advice from Cardinal von Goes and Cardinal Kollonitz. When the two Cardinals arrived in Rome, there developed an intense struggle for leadership among Lichtenstein, Medici, Medinaceli, and Goëss [cf. Goëss' letter of February 17 and 24 to the Emperor]. All kept up a correspondence with Vienna, which fed contradictory information to the Emperor. This disorganization worked to the disadvantage of the Imperial-Spanish group.

The recently retired Venetian Ambassador to Rome, Girolamo Lando, noted in his speech to the Doge and Senate on April 7, 1691, that Cardinal Ottoboni seemed to claim control over some twelve votes (though actually only ten):

Il cardinale Ottoboni resta capo di una fazione considerabile di 12 cardinali, che detratti Fonobia [Forbin?] e Giudici, dipendenti l'uno di Francia l'altro da Spagna, restano dieci.

In the first scrutiny, the Franciscan Cardinal, Francesco Lorenzo Brancati di Lauria, who was seventy-nine years old, received sixteen votes. Apparently the advanced age of the two previous popes—Innocent XI died at seventy-eight and Alexander VIII at eighty—did not deter some cardinals for looking for a leader among the decrepit and senile. Brancati had a reputation for learning and piety, but he was of peasant stock and monkish, which repelled a number of cardinals. But Brancati was also opposed by the Spanish, even though he himself was of Spanish origins, since he had always opposed them, and therefore his candidacy did not progress [Fleury Volume 66, p. 2]. The original book recording the results of the scrutinies survives in manuscript Vaticanus Latinus 8228 [Vincenzo Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 187, no. 583].

On the night of February 27 (not—as the author of the Histoire des Conclaves (p. 91) has it—around Pentecost, a tasteless joke perhaps), a fire broke out in the Conclave near the cell of Cardinal Lorenzo Altieri, lasting more than five hours. Cardinal d'Este wrote the next day to the Duke of Modena, his brother [Petruccelli III, 385-386; trans. Pirie, p. 214-215, whose account, however, is placed after the French arrival, which, on p. 212, she erroneously places on March 19; on the 17th the French Cardinals had only arrived at Livorno]:

Last night the conclave caught fire, and the conflagration lasted till the early hours of the morning. I cannot tell you the panic it caused among us. The danger was great no doubt, but the burlesque was greater still. I could have held my sides at the sight afforded by my dear colleagues in raiment and attitudes that Jacob under his ladder would never have dreamed of. This one in a camisole, that one in pants, another in a dressing gown, a fourth wrapped up in wadding, others in vests, or shirts, or strange indescribable garments—but all irresistibly comical. Cardinal Marescotti, who had been laid up for four days unable to move with lumbago—miraculously cured by fright—was rushing about half naked, as hairy as a devil, and repeating incessantly: What next, good heavens, what next? Aguirre, who usually needs the support of four attendants, was gambading along the passages like a frolicsome hare. Maidalchini, who is afflicted with a hernia, flew past holding it up in both hands. Bouillon, scratching himself unrestrainedly, was screaming to his servants to save his periwigs. Forbin, under pretext of saving valuable documents, was searching the cells for compromising papers of which he held large rolls under his arms. Colloredo and S. Susanna marched solenmly round holding a crucifix and chanting: Libera nos Domine. Ottoboni, in spotless white night attire, his face fresly painted, was cutting capers, joking and laughing like a lunatic.

According to Cardinal de' Medici, writing to the Emperor [Petruccelli III, 375], there were two factions inside the Conclave. One of them had twenty-six members, and included the French, Altieri, Ottoboni and some of the Cardinals created under Innocent XI. The other had thirty-seven members, including the Austrians, Chigi, some of Innocent XI's cardinals, some Zelanti, and some refugees from Altieri and Ottoboni. Chigi and his associates wanted Barbarigo, and consequently the others rejected him.

Cardinal Barbadigo: excluded

For some time Gregorio Cardinal Barbadigo seemed likely to prevail in the scrutinies. He was a person both of integrity and episcopal experience, and he was only sixty-six. At the age of 23 he had been a junior Venetian diplomat in Münster at the negotiations that led to the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). There he attracted the attention of Cardinal Fabio Chigi (who became Alexander VII). In 1655 he obtained a doctorate in canon and civil law, and was ordained a priest that December. He was initiated into the papal service by Alexander VII, who elected him Bishop of Bergamo in 1657. He had been a successful Bishop of Bergamo, and Pope Alexander VII had promoted him to the Cardinalate in 1660. In 1664 he was promoted to the Bishopric of Padua. He had age, seniority, learning and experience both of international affairs and church administration in his favor. And he was a fervent Christian. He had been papabile in the Conclave of 1689, and had more supporters in the Sacred College than any other candidate. But he was unable to secure two-thirds of the votes of his brother Cardinals. The French were certainly no friends of the leading creature of Alexander VII, who had not served the interests of France as well as he had those of the Church at Westphalia. The annoyance of Louis XIV and the French had never dissipated. In addition, both Cardinal Altieri and Cardinal Ottobono were against him, and each had a faction of supporters. That, at least, was the propaganda put out by Cardinal Forbin Janson, who knew, however, that Barbarigo was not unacceptable to the French. But everyone knew that Forbin Janson was an intimate of Louis XIV, and they believed that he was expressing the mind of his master. But his efforts had the effect of impeding the swift election of Barbadigo and gave the French cardinals time to arrive in Rome. In the meantime the Zelanti sent messages to the Queen of England (Mary of Modena), and Père Lachaise, Louis XIV's confessor, to convince him to withdraw his objection to Barbarigo (Petruccelli III, 369). Ironically, it was the Emperor who ended Barbarigo's chances, on March 12, by sending word that he wished to exclude him [Despatch from Vienna on March 4: Wahrmund, 170-172]. On the 14th of March Cardinal Medici wrote to Leopold in Vienna that carrying out his orders of the 4th of March for a formal exclusiva would have negative reprercussions among the public (Wahrmund, 291):

sarà apparente al publico, che sia tenuto addietto un soggetto, che per consenso commune si giudiica degno e irreprensibile senza occasione o motivo, che possa per aventura sodisfare l' attenzione del mondo sopra la sua esclusione, che puo darsi il caso, che negli animi degli zelanti e forse d' altri prevaglia lo stimolo della propria coscienza a qualunque riguardo, e che potesse da qualche valida opposizione restar vulnerato il decoro da Sua Imperial grandezza....

Cardinal Goëss wrote immediately to the Court Chancellor, Graf Strattmann, on March 17 [Wahrmund, 291] that the news of the authorization of an exclusiva had caused a great commotion at the Conclave, particularly among the Zelanti; he had heard that the French Cardinals had just arrived in Livorno, and that when they arrived they would use the opportunity to stir up hatred against the Imperial interest. After this, when the French Cardinals finally arrived, towards the end of March [Petruccelli III, p. 367], it became known that Barbarigo was in fact acceptable to the King of France. Cardinals Bouillon, d'Estrees, Bonzi and Camus arrived in Rome on the 25th of March and entered Conclave on March 27, increasing the faction which, at the time, thanks to the efforts of Cardinal Forbin, included the supporters of Cardinal Altieri and those of Cardinal Ottoboni. But Barbarigo still did not have two-thirds of the electors. His name continued to be at the top of the scritinies all the way through July 7 [letter of Cardinal Goëss to the Court Chancellor in Vienna: Wahrmund, 301].

Valerie Pirie [The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves p. 213] claims that the name of Barbarigo was first proposed on April 4, and that it came as a complete surprise:

The cardinals had agreed to await their French colleagues before proceeding to elect the pope; but they could scarcely be expected to postpone the scrutinies indefinitely; so on April 4th Chigi suddenly proposed the candidature of Barbarigo, and attempted to carry off his election by surprise. D'Estrées, who was by now a more experienced conclavist, far from opposing the Venetian prelate, appeared to be most favourably inclined towards him, and merely asked for time to obtain the King's consent to his elevation.

This account, based almost entirely on Petruccelli, but with a defective chronology and an exclusive interest in the French, is erroneous and completely misleading. There was no surprise of any sort on April 4 or on any other day. The German sources indicate that Barbarigo was the most serious candidate and the most discussed, before and during the Conclave.

The next to be proposed was Cardinal Giovanni Delfino of Venice, the former Ambassador to France of the Serene Republic. He had the support of the French and their allies. But the Zelanti dug in their heels, fearing that Delfino would engage in large scale nepotism, as had the deceased pope, a fellow Venetian. Cardinal Negroni went about the Conclave one evening, pointing out the features of Delfino's career and those of his nephews, his many nephews, whose moral conduct was not beyond criticism. At the same time Cardinals Pallavicini and Colloredo canvassed their colleagues, pointing out that any hope of restoring discipline in the Church and providing spiritual leadership in the Papacy would be lost if Delfino were selected. They managed to accumulate 33 votes for Barbarigo and against Delfino and successfully imposed the virtual exclusiva [letter of Cardinal de Medici to Leopold I, April 24, 1691: Wahrmund, 300]:

De Em(inentissim)o Delfino in Summum Pontificem eligendo ab aliquot suis fautoribus actum fuerat, at quam primum huiusmodi consilium a Zelantibus penetratum fuerat, quo suam a Delfino alienationem ublicam facerent, 33 vota in Barbadicum contulerunt. Ex quo satis patet, eosdem nunquam in Delfinum consensuros.

After Delfino, some proposed Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri, the "nephew" of Clement X. Cardinal Altieri was very acceptable to King Louis, but in other quarters the very mention of his name brought more recollections of the abuses of nepotism in earlier papacies, and he was rejected. The fact that the number of votes for Cardinal Brancati began to increase again seems to indicate that Cardinals were being cautious in spreading their votes around among candidates who could not win, lest they arouse and ruin the hopes of any genuine viable candidate before the right moment.

On April 20, the French Ambassador, the Duc de Chaulnes electrified the Conclave by announcing that the French had captured Nice, and that on Palm Sunday the city of Mons in Hainault had fallen into their hands (in the war against William of Orange). He demanded that the College support the efforts of the Catholic princes, Louis XIV and James II, to preserve and spread the Catholic religion.

The Ambassador of Venice later put in an appearance, demanding that the Cardinals order the papal galleys to support the Venetians in their war agains the Turks, who had now reached Belgrade. The Cardinals replied that their one and only legitimate task was to elect a new pope.

On May 30, the Vicar of Rome, Cardinal Carpegna, issued a decree to the Clergy of Rome to conduct processions and celebrate Holy Communion generally in order to obtain God's blessing on an early election.

By this point the Conclave had been in progress for more than five months. The next to be placed under scrutiny was the sixty-one year old Florentine, Cardinal Acciaiuoli, another candidate of Cardinal Chigi (though a secret one, since Chigi had spent his influence on Delfino). On July 7, Cardinal Goëss wrote to Vienna [Wahrmund, 301] that the Barbarigo exclusiva was still an issue, but that they had been working against the candidacy of Cardinal Acciaioli for more than a week. The Spanish Ambassador was helping, but was reluctant to proceed too far without specific instructions from Madrid. He was so far acting on only general instructions to assist the Imperial faction. Acciaioli had the support of the French and Medici, and the Zelanti were favorable. Acciaiuoli was very close to election. But opposition developed from both the faction of Cardinal Ottoboni and the faction of Cardinal Altieri, due to longstanding competitive interests. The Austrians joined them to exclude the Florentine with a virtual veto.

Cardinal Pignatelli

On June 30, Prince Lichtenstein wrote to the Emperor, quid ... de hujus conclavis exitu referam, nihil habeo, persistentibus in Barbarigo Zelantibus, contradicentibus vero Alterianis et Ottobonianis cum Gallis conjunctis. Ab opinione vix recedent Zelantes, quamdiu Galli Barbadicum positive non excluserunt [Wahrmund, 301]. But, also on June 30, out of frustration at the failure of Barbarigo and then of Acciauoli, twenty-eight cardinals who were friends of Cardinal Barbarigo (not a majority of the Sacred College) united to solicit the King of France to consent to the election of Barbarigo. This was to the liking of d'Estrées. The French opposition to Barbarigo, then, was without doubt headed by Forbin Janson, the King's Ambassador in Rome. The twenty-eight Cardinals sent their letter to King James of England to pass on to Louis XIV personally and to speak on behalf of the cardinal. The amazing thing is that some such move had not been tried two months earlier. Two different couriers were dispatched, by two different routes. But the French cardinals prevented one courier from reaching Paris, though the other completed the journey—but arrived too late to have his dispatch acted upon effectively. Cardinal Forbin Janson began instead to work on behalf of Cardinal Antonio Pignatelli, while the other French cardinals sent their own messenger to Paris to determine what the King's opinion of Pignatelli was [Petruccelli, p. 399]. Antonio Pignatelli was a creatura of Innocent XI and a subject of the King of Spain ([Leti], Histoire du conclave d' Innocent XII, p. 96). At the same time the Zelanti launched a counter-measure, threatening to nominate the Neapolitan Cassanata or Marescotti. Clearly they had no intention of giving up, even if they were denied Barbarigo. Equally clearly, neither a French candidate nor an Imperial candidate could draw sufficient votes.

On July 7, the Imperial Ambassador, Prince Lichtenstein, wrote to Vienna [Wahrmund, 301] in complete frustration, seeing no exit from the 'Labyrinth of passions' (as he termed the Conclave):

In iisdem fere intricatissimi huius conclavis si alias unquam haerent negotia, nec invenitur filum, quod ex hoc passionum labirinto exitum indicet; a Barbarigo nunquam nisi excisa omni spe recedent Zelantes, in hunc nunquam consentient Alteriani et Ottoboniani, nisi coacti vel a Gallis derelicti, ad exclusivam apertam vix devenient isti, qua pacto intentum obtinent.... Unum porro humillime gratulor, nec parum profecto conferri ad stabiliendam Sac(r)ae Caes(aris) Reg(is) M(ajesta)tis Romae abolitam authoritatem, quod scilicet res ita in Hispania dispositae fuerint, ut huius Coronae orator nationalesve Card(ina)les non aliis mandatis instructi sint, nisi ut Caesareis consiliis penitus adhaereant, iamque Sac. Caes. Reg. M. V. quod a tempore Caroli Quinti vix evenit, primarios huius scenae partes sustineat, quas in posterum conservare haud difficile erit, si arma Caes(are)a in Italia contra Gallos praevaluerint....

As Cardinal Medici remarked to his brother (letter of July 11), the heat and the illness prevalent in the Conclave were having their effect. That argument was used on Cardinal Altieri by the leaders of the other factions. On the 9th, the French had a conversation with Cardinal Pignatelli, promising him their support if he would agree to select his ministers according to the wishes of the King of France. Pignatelli agreed [Petruccelli III, p. 399]. On Monday, the 10th, the prattica for Pignatelli really began in earnest. Chigi was pressing everyone he could meet with to make a decision. He went to Altieri, Ottoboni and Pallavicino to get them to put pressure on the French to end their obstructionism. Forbin Janson was working on the other Frenchmen, and at a meeting that evening finally got them to listen to his arguments. The problem was Cardinal Goëss, whose mysterious manner and unwillingness to agree or disagree exasperated the other heads of factions. On the 11th, the French finally seemed more reasonable, and opinions were beginning to coalesce on Pignatelli. Medici mangaged to get the vote of Cardinal Howard. Finally, on Thursday, July 12, a compromise was reached. The candidate, the sixty-six year old Antonio Pignatelli, Archbishop of Naples (Innocent XII, 1691-1700), was satisfactory to the French. He was escorted to the chapel by Cardinals Forbin and d'Estrées. He received 53 of 61 votes [Fleury 66, p. 4]. Among the seven dissenters were: Carpegna, Corsi, Denoff, Kollonitz and Negroni—the core of the Zelanti. [Petruccelli III, p. 403].

The announcement was made to the public from the central outside window of the loggia of the Vatican Basilica around 14:00 by Cardinal Sacchetti. In the meantime the new Pope and the cardinals had lunch. During this time the walls of the Conclave area were being broken down. Around 16:00 the participants returned to the chapel for the Second Adoration. When that was concluded, the Pope was escorted on his Sedia gestatoria to the Vatican Basilica, where the Third Adoration took place. The Pope then imparted his blessing to the people.

Coronation

Innocent XII was crowned on Sunday, July 15. On that same day Cardinal Spada was named Secretary of State [Campello, 173]. The Pope took possession of the Lateran Basilica on April 13, 1692, with Cardinal Maidalchini presiding at the Basilica in place of Cardinal Chigi, the Archpriest [Cancellieri, pp. 313-324].

Cardinal Fabrizio Spada was named Secretary of State, and Cardinal Bernardino (Bandino) Panciatici became Datary. Cardinal Gian Francesco Albani was named Secretary of Private Briefs, and Prince Mario Spinola Secretary of Briefs to Princes. Msgr. Ercole Visconti was named Maggiordomo, and Msgr. Baldassare Cenci became Maestro di Camera. On July 26 Innocent named Msgr. Giovanni Battista Spinola as Governor of the City of Rome; Spinola was created a cardinal on December 12, 1695. On July 31, Pope Innocent went to the Gesù, to celebrate the Feast of S. Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus. On August 3, he went to S. Maria sopra Minerva to celebrate the feast of S. Dominic Guzman, founder of the Order of Preachers.

Bibliography

Fulvio Astalli, Giornale del Conclave dell'anno 1691, nel quale segui l' elettione di Innocenzo XII, per la morte d' Alessandro VII 5 volumes (Codex Vat. 8228, 8229, 8230) [Vincenzo Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma I (Roma 1879), p. 187, no. 583, 584, 585]. Angelo Peretti, Diario di quanto e accaduto nel Conclave seguito l'ann. MDCICI. nel quale e stato eletto in pontefice Innocentio XI., an unpublished manuscript in Codex Ottobonianus 490 [Forcella, Catalogo dei manoscritti relativi alla storia di Roma II (Roma 1880), pp. 18-19]. [February 12 to July 12]

Relazione dell' ultima Infermità e Morte della Santità Di N.S. PP. Alessandro Ottavo Pontefice Ottimo Massimo (Roma: Giovanni Francesco Buagni 1691). Esatta Descrizione dell' Essequie fatte nelle Basilica Vaticana alla Santità di N. S. PP. Alessandro VIII. (Roma Giovanni Francesco Buagni 1691). Conclave fatto per la Sede Vacante d' Alessandro VIII, nel quale fù creato Pontefice il Cardinale Antonio Pignatelli Napolitano, detto Innocentio XII alli 12. di Luglio 1691 (Colonia: Lorenzo Martin 1692). [Gregorio Leti] Histoire des Conclaves depuis Clement V. jusqu'à présent troisième édition, tome second (Cologne 1703) [caution! highly unreliable].

P. Campello della Spina, "Pontificato di Innocenzo XII. Diario del Conte Gio. Battista Campello," Studi e documenti di storia e diritto 8 (1887), 167-198. [an eyewitness narration of the announcement of the Election, of the public ceremonies of that day, and of the Coronation; Campello was Auditor and Conclavist of Cardinal Rubini, Secretary of State of Alexander VIII]

Mario Guarnacci, Vitae et Res Gestae Pontificum Romanorum et S. R. E. Cardinalium a Clemente X. usque ad Clementem XII. Tomus primus (Romae: Venantii Monaldini 1751). Lorenzo Cardella, Memorie storiche de' Cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa Tomo settimo (Roma: Pagliarini 1793). [Consistories of 1641-1689]

Claude Fleury, Historia Ecclesiastica Tomus LXV (Augustae Vindelicorum: Josephi Wolff 1781), Lib. CCX; Tomus LXVI (1781), Lib. CCXI. Francesco Cancellieri, Storia de' solenni Possessioni de' Sommi Pontefici, detti anticamente Processi o Processioni dopo la loro Coronazione dalla Basilica Vaticana alla Lateranense (Roma: Luigi Lazzarini 1802). G. Novaes, Elementi della storia de' sommi pontefici Vol. XI (Roma 1822) 106-108. Alexis François Artaud de Montor, Histoire des souverains pontifes romains VI (Paris 1851) 206-207, repeats Novaes' notes, neither one having any insight. G. Moroni, Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica Vol. 36 (Venezia 1846) 32-33 adds nothing. Ferdinando Petruccelli della Gattina, Histoire diplomatique des conclaves III (Paris 1865) 351-403. Ludwig Wahrmund, Das Ausschliessungs-recht (jus exclusivae) der katholischen Staaten Österreich, Frankreich und Spanien bei den Papstwahlen (Wien: Holder 1888) [with a rich collection of documents in the Anhang]. Sigismund von Bischoffshausen, Papst Alexander VIII und der Wiener Hof (1689-1691) (Stuttgart-Wien 1900). Valerie Pirie, The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1936), Innocent XII, pp. 211-219.

Conjectures politiques sur le Conclave de MDCC & sur ce qui s'est passé à Rome pendant la maladie, et aprés la mort du Pape Innocent XII. pour l' election d' un successeur (A Parme: Chez Innocent Treize, MDCC).

J-T. Loyson, L' Assemblée du clergé de France de 1682 (Paris: Didier 1870). Léon Mention (editor), Docments relatifs aux rapports du Clergé avec la Royauté de 1682 à 1705 (Paris 1893). Charles Gérin, "Le Pape Alexandre VIII et Louis XIV," Revue des Questions historiques (1877) 135-210. ["...fait avec une partialité si criante en faveur de [Alexandre VIII] que son étude peut et doit être considerée comme la contrepartie même de l' histoire"—E. Michaud, p. 7]. E. Michaud, La politique de compromis avec Rome en 1689: Le Pape Alexandre VIII et le duc de Chaulnes (Berne 1888). P. Blet, "Louis XIV et le Saint Siège," XVIIe Siècle, no. 123 (1979), pp. 137—154.

Pietro Maria Puccetti, Vita del Cardinal Leandro Colloredo (Roma: Rosati e Borgiani 1738). G. Tabacchi, "Cardinali zelanti e fazioni cardinalizie tra fine Seicento e inizio Settecento," in G. Signorotto (editor), La corte di Roma tra Cinque e Seicento. "Teatro" della politica europea (Roma: M.A. Visceglia 1998) 139-165.

© 03/28/2006