Sede Vacante 1410

May 3—May 17, 1410

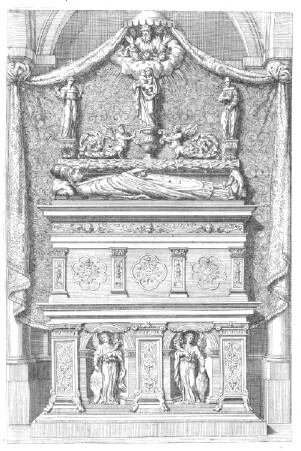

Church of S. Francesco in Bologna

Site of the Tomb of Alexander V and Site of the Conclave of 1410

The Council of Pisa

Frustration among European leaders, lay and clerical, had been growing for years. The schism which had begun in 1378 over the elections of Urban VI and Clement VII, had led to greater and greater acrimony among the contending parties, to the political annoyance and spiritual angst of people of every sort of commitment. A first way to solve the problem had been tried by Charles of Anjou, who took his army into Italy, intending to take his Kingdom of Naples, left to him by his adopted mother, Queen Johanna, and to destroy Urban VI, who had humiliated and ruined Queen Johanna. But the Via Belli was not acceptable to the Church, its theologians or its canon lawyers. A set of strategies had been worked out for ending the schism, but neither pope could be brought to embrace one of them. Even after the deaths of Urban and Clement, their successors continued the squabbles, and, though they talked repeatedly about healing the schism, practical measures to do so were defeated by quibbling and tergiversation (Sauerland, passim.). The option that both popes should simultaneously resign so that a new pope, acceptable to all sides could be elected (the Way of Cessation, Via Compromissi), was popular, and was embraced by one or another pope according to his strategy of the moment. But it was never carried into effect. Finally, the Way of the Council, either of a Particular Council, with limited attendance, to bring about a double resignation, or a General Council of all prelates (Via Concilii) was adopted by one interested bystander after another, as the only solution by which Christendom might heal itself without the assistance of two obstinate Popes . [See, e.g., the presentation of Nicholas Clemangius to King Charles VI of France on behalf of the University of Paris, June 6, 1394, before the death of Clement VII: Du Boulay, Historia Universitatis Parisiensis 4, pp. 687-699].

Pope Gregory had fled from Rome and the tyranny of the Condottiere Paolo Orsini on August 9, 1407. He took up residence in Viterbo, intending (so he said) to travel to the meeting with Benedict XIII which was being planned for Savona. In September, he and eight cardinals arrived in Siena, where, thanks to the presence of the French (whose famous marshal Boucicault was governing Genoa on behalf of King Charles), he was able to claim that Savona was no longer a safe place for him to appear. Negotiations began again towards finding an appropriate site for a meeting between the two popes. Negotiations were managed by Gregory's nephews, who were in no hurry to end the schism and their own influence. Gregory, in fear of the fleet that Benedict XIII had in northern Italy, removed himself to Lucca (where he stayed until his return to Siena on July 14, 1408) and suspended negotiations. In the meantime, King Ladislaus saw his opportunity; he offered bribes to Paolo Orsini to put Rome into his hands, but when the Romans discovered what was being contemplated, they themselves made a treaty with the King and gave him control over all of their fortresses and over the government of their city. On April 25, 1408 King Ladislaus of Sicily entered Rome in triumph. His troops occupied the Patrimony of St. Peter and Umbria, and he was recognized by Amelia, Assisi, Orte, Perugia and Todi. At the end of June, leaving behind a committee (including Cristoforo Caetani, Lord of Fondi) to rule the city for him, he returned to Naples. Papal government in central Italy was nearly extinguished. Amazingly, Gregory did not even recall his ambassador to Naples.

In May of 1408, Pope Gregory decided to create new cardinals [Theoderic de Nyem de schismate III. 31]. His failure to arrange a meeting with Benedict XIII and to resign if necessary to end the schism, as promised in 1406 during the Conclave and again before his coronation, was already a major irritant:

... si quis eorum assumptus fuerit ad apicem summi Apostolatus, pro redintegratione unitatis christianorum, renuntiabit et cedet praetensis juri suo et papatui, sive decedat, dummodo anticardinales effectualiter velint cum eisdem dominis sacri collegii sic convenire et concordare, quod ex sacro collegio et ipsis sequatur justa canonica electio unici summi Romani Pontificis....

He had also agreed and sworn not to create new cardinals, except to keep his own college on a par with the cardinals of Benedict XIII:

pendente tractatu unionis hujusmodi effectualiter et realiter ex utraque parte non creabit nec faciet aliquem cardinalem nisi causa coaequandi numerun sui sacri collegii cum numero perversi collegii anticardinalium praedictorum, nisi ex defectu steterit adversae partis, quod unionis praefatae conclusio infra annum a fine dictorum trium mensium computandum non fuerit subsecuta....

There was certainly no need to do that in May of 1408. The older cardinals, moreover, were so indignant at Gregory's four choices (tainted as they were by nepotism), and the fact that the cardinals themselves had not been consulted in Consistory beforehand, that they refused to attend the Consistory for the installation ceremonies on May 12, 1408. Gregory's angry reaction caused them to wonder whether they might become victims of retaliation, as six of Urban VI's cardinals had been. On Wednesday, May 11, 1408, Jean Gilles, the Cardinal of Liège (who died July 1, 1408), removed himself from Lucca, where the Pope was in residence, and went (first) to a castle held by the Florentines some four miles away, and presently to Pisa. The Pope's nephew Paolo Corrario pursued him with troops, attempted to catch him and to bring him back a prisoner, but without success [Gregorovius, 600-601]. The papal violence was so shocking, however, that seven more cardinals deserted Lucca along with their retinues that same evening, and made for Pisa. They were Angelo Acciaioli (Bishop of Ostia), Antonio Gaetani (then Bishop of Palestrina), Corrado Caraccioli of S. Crisogono, Giordano Orsini (then of SS. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti), Rinaldo Brancaccio of Ss. Vito e Modesto, and Oddone Colonna of S. Giorgio in Velabro. Cardinal Petrus Blavi of S. Angeli arrived in Lucca on the same day, May 11, and departed the next morning for Pisa. No doubt to prove that he was in the right, Gregory XII further amplified the number of his cardinals in September of 1408 with nine more members. Again, there was no need and no consultation, and further offense was given to the cardinals at Pisa. The Council of Pisa in its fifteenth session, June 5, 1409, demonstrated the importance of Gregory's offense in creating new cardinals by annulling the creations of May, 1408 [Mansi 27, 404]:

Et insuper omnes promotiones, immo verius profanationes quorumcumque ad cardinalatum per dictos contendentes de papatu, vel eorum utrumque attentatos, per dictum Angelum a die tertia Maii, et Petrum antedictum a die XV. Junii anni proxime praeteriti MCCCCVIII. fuisse et esse nullas, cassas, irritas et inanes, et quatenus de facto proceserunt, de facto annullandas, cassandas, et irritandas, et sic et etiam ad cautelam quatenus expediat omni modo et jure quibus melius potest, praefata sancta Synodus per hanc definitivam sententiam cassat, irritat et annullat...

Actual preparations for a General Council began with the sending of an embassy by Pope Benedict XIII to Italy, around May 20, 1408. Four cardinals led the embassy: Guy de Malsec (Bishop of Palestrina), Pierre de Thury, Pierre Blau (died December 12, 1409), and Antoine de Chalant (Ehrle Archiv 7, p. 635, 644; Valois, 4). They were also to sound out the Cardinals of Gregory XII as to the prospects for Church union. Benedict XIII's instructions for the Embassy survive. Three of his four cardinals, to his great anger, found common cause with Gregory's alienated cardinals. On June 29, 1408, thirteen cardinals who were gathered in a meeting at Livorno (who also had the proxies of two other cardinals) undertook a series of promises directed toward the holding of a General Council of the Church for the healing of the schism. Within a few months, seven more cardinals subscribed to the Livorno declaration.

Deposition of Gregory XII and Benedict XIII

On January 26, 1409, the Florentines withdrew from obedience to Pope Gregory [Baronius-Theiner, p. 233 n. 1]. Since Pisa was in Florentine territory, this was yet another blow to Gregory XII's influence over central Italy and over events.

The Council of Pisa held its opening ceremonies on March 25, 1409. On June 5, 1409, at its Fifteenth Session, the Council of Pisa deposed and anathematized both Benedict XIII and Gregory XII as notorious schismatics, heretics and perjurers:

... ipsoque Angelum Corrario et Petrum de Luna de papatu, ut praefertur, contendentes, et eorum utrumque fuisse, et esse notorios schismaticos, et antiquitati schismatis nutritores, defensores, fautores, et approbatores, et manutentores, pertinaces, necnon notorios haereticos et a fide devios, notoriisque criminibus enormis perjurii et violatione voti irrretitos, universalem ecclesiam sanctam Dei notorie scandalizantes, cum incorrigibilitate, contumacia et pertinacia notoriis, evidentibus et manifestis, et ex his ac aliis se redidisse omni honore et dignitate etiam papali indignos, ipsosque et eorum utrumque propter praemissas iniquitates, crimina et excessus, ne regnent vel imperent aut praesint, a Deo et sacris canonibus fore ipso facto abjectos et privatos, ac etiam ab ecclesia praecisos; et nihilominus ipsos Petrum et Angelum et eorum utrumque per hanc definitivam sententiam in his scriptis privat, abjicit, et praescindit, inhibendo eisdem, ne eorum aliquis pro summo pontifice gerere se praesumat, ecclesiamque vacare Romanam ad cautelam insuper decernendo....

Death of Pope Alexander

According to Theoderic of Nyem [de schismate III. 51; p. 321 Erler], Pope Alexander began to show signs of illness in October, 1409, only four months after his election. On October 30, he came to Prato. In November, Baldassare Cossa returned from Tuscany, where he had been assisting King Louis d' Anjou, and found Alexander at Pistoria. The papal court was compelled to leave Pistoria, however, because of the extreme cold that winter and because a pestilence had begun to appear in Pistoria (at least according to Theoderic, de schismate III. 53; p. 327 Erler; Baronius-Theiner 27, sub anno 1410, no. 5, p. 303); Sozomen of Pistoria says that the pestilence caused the Papal Court to leave Pisa for Pistoria; the date was October 25 (Erler, p. 323 n. 5). On November 1, Louis d'Anjou, Cardinal de Thuryeo, and the Master General of Rhodes arrived in Prato and had an interview with the Pope. On November 7, the Curia left Prato for Pistoria. On the same day, Louis, de Thuryeo and the Camerarius François de Conzieu, Archbishop of Narbonne, left for Provence. Theoderic complains that his secretariat was in disorder the whole time , and engaging in many irregularities, because the generous pope had lent many of his curiales to King Louis. At another place, however, Theoderic says (maliciously) that it was Cardinal Baldassare Cossa who made Alexander leave Pistoria and travel to Bologna:

persuasionibus et promissis hujusmodi praedicti Balthasaris inducti, in illo indisposito et frigido tempore hyemali, per asperos montes et vias terribiles inter Pistorium et Bononiam, tunc repletos glaciebus et nivibus, de ipsa civitate Pistoriensi ad Bononiam accesserunt

It is also true, however, that on December 31, 1409, Rome had been delivered from the tyranny of King Ladislaus, thanks to the appearance of King Louis II d'Anjou in Italy, and the expedition against the City undertaken along with Baldassare Cossa, Carlo Malatesta, Francesco Orsini and Paolo Orsini. On January 1, 1410, Malatesta, Orsini and Lorenzo Anibaldi entered the City. Opposition, however, continued sporadically until May 1. But on February 12, ambassadors from Rome had presented Pope Alexander with the keys of the city and requested his presence there. Their plea was supported by the Florentines [Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1409, no. 85-87, pp. 292-296; Gregorovius, pp. 608-612]. The good news from Rome was enough to draw Alexander southward. Whether Cardinal Cossa tried to keep the pope in Bologna, as is alleged, is a disputed matter. If he did so, it might just as well have been out of prudence (he had recently seen the situation in the neighborhood of Rome, for he had been with the armies personally) as of self-interest.

Finke's anonymous Chronicon indicates that Alexander V died in Bologna on the night of May 3/4, [Romische Quartalschrift 4, 353]: [Alexander Papa V] obiit anno domini M.CCCC.X., die sabbati tercia maii de sero, hora quinta noctis [Saturday, May 3, 1410, around 10 p.m.] in Bononia, et fuerunt peracte exequie, prout scripsi de exequiis Innocencii septimi. The letter sent by the Cardinals to the University of Paris on May 17, the day of the election of John XXIII, states that Pope Alexander died on May 4, die quarta praesentis mensis ab hac luce subtracti—though this is surely only a matter of when the beginning of the day is counted; the Roman tradition was sunset, while other places used other points in the day. Petrus Plaoul, Bishop of Senlis, wrote to the University of Paris on May 4 that the Pope had just died [Denifle, Cartularium Universitatis Parisiensis IV, no. 1881]. The body was carried from the Apostolic Palace [Palace of the Podestà] to the Church of St. Francis on Monday, May 5, where the funeral took place [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1410, p. 310; Religieux de Saint-Denys 31. 7]. Et fuit sepultus Bononiae in ecclesia fratrum Minorum et die mercurii XIIII. mensis maii [Wednesday, May 14, 1410] domini cardinales intraverunt conclave in Bononia. The Novendiales began on the next day, Tuesday, May 6, and at the Requiem Mass the sermon was preached by the General of the Franciscans, Antonio de Periocto (Ponto), in whose Church of St. Francis the burial and the Novendiales were taking place. They concluded on Wednesday, March 14 [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1410, p. 310].

The Indictment of Baldassare Cossa, prepared for use at the Council of Constance in May of 1415, charges John XXIII with conniving in the poisoning murder of Pope Alexander along with the Pope's doctor, Daniel de Sancta Sophia:

in mortem bonae memoriae domini Alexandri papae quinti extitit machinatus; et ut tam ipse quam medicus suus magister Daniel de sancta Sophia artium et medicinae doctor veneno extinguerent, prout extincti sunt, poeram dedit

Prosecutors regularly throw such material into indictments, however, not to indicate that they can prove the charges, but to win the maximum interest in their case. The charge is unsupported by evidence or witnesses elswhere. It was never argued before the Council, and it should not be treated seriously. The Annales of Lorenzo Bonincontri [Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores 21, column 103] mention the story of poisoning, only to dismiss the notion:

Alexander Pontifex discedens Pistorio, Bononiam ivit, a Bononiensibus honorificentissime susceptus. Sed V. Maji moritur. Sunt qui dicant perisse veneno per Legatum Cossam exhibito. Parum id constat.

The Cardinals

At the opening of the Council of Pisa on March 25, 1409, there were fourteen cardinals (or sixteen cardinals: nine Italians and seven French) in attendance. As of the end of June, 1408, there were twenty-six living cardinals: fourteen of the Roman Obedience and twelve of the Avignon Obedience. Cardinal Angelo Acciaioli died at Pisa on May 31, 1408. Cardinal Jean Gilles died at Pisa on July 1, 1408. The two popes, however, had only four cardinals on their sides [Souchon II, p. 41]. Eighteen cardinals attended the Council of Pisa, according to a ms. cited in J. D. Mansi [Sacrorum Conciliorum 27, columns 331-33; cf. Souchon II, p. 41 n. 5; leaving out Petrus Fernandi S. Praxedis, Francesco Uggucione, Baldassare Cossa, and Louis de Bar]; the total number in attendance at one time or another was in fact twenty-two [Mansi Sacrorum Conciliorum 26, columns 1239-1240], not counting Gilles or Acciaioli. They were all excommunicated, anathematized, and deprived of their cardinalates by both Benedict XIII or by Gregory XII (May 16, 1408, e.g. Theodericus de Nyem, de schismate III. 33, p. 284-285 Erler).

As far as the Conclave of May, 1410, is concerned, Onuphrio Panvinio, Epitome pontificum Romanorum (1557) (pp. 279-280), lists seventeen cardinals as present, and seven as absent [He includes Alfonso Carillo as "absent"; but Carillo actually supported Benedict XIII and did not recognize the Council]; his material is based on Theoderic de Nyem, as Souchon (II, p. 41 n.1) has pointed out. A list of twelve Cardinals, who attended a meeting in the Sacristy of the Franciscan church in Bologna, is given in a notarized document of May 13, 1410 [Martène-Durand VII, 1179]. This was the day before the Conclave began. A list of eleven cardinals is given in the bull of excommunication issued by Gregory XII in 1411 [Baronius-Theiner 27, pp. 319-320 (Holy Thursday, 1411)]. A list of all twenty-three cardinals who participated in May of 1410 is given by "Tillius" in his Tabularium ex antiquis Monumentis Ioannis XXIII [quoted in Baronius-Theiner, p. 310]. A list of twenty-two cardinals is given by the Religieux de Saint-Denys. Ehler, in his edition of Theoderic de Niem (p. 328 n. 1), provides another list of the 23 participants. Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica I, p. 32 n. 3, lists 23 electors. Another list is provided by Jacques Lenfant, Histoire du Concile de Pise I, pp. 350-351. Souchon II, p. 97.

On the absent cardinals from among the electors: Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1410 no. xvii, p. 311. The correct number of absentees is six, as can be determined by counting their names, rather than trusting to the arithmetic of the source.

The still-loyal cardinals created by Gregory XII (Angelo Corraro) did not participate. They were few in number, for on December 14, 1408, he had deprived most of the members of his Sacred College of their status as cardinals. Those deprived, all of whom participated in the election at Bologna, were [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1408, nos. lxvi, p. 227]:

- Antonius Gaetani, Aquiliensis, Cardinal Bishop of Palestrina

- Henricus, Neapolitanus, Cardinal Bishop of Tusculum

- Corradus Militensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Crisogono

- Jordanes de Ursinis, Cardinal Priest of S. Martini in Montibus

- Petrus, Mediolanensis, Cardinal Priest of Basilica XII Apostolorum

- Johannes, Ravennatis, Cardinal Pirest of S. Crucis in Jerusalem

- Angelus, Laudensis, Cardinal Priest of S. Pudenziana

- Raynaldus de Brancaciis, Cardinal Deacon of SS. Viti et Modesi

- Baldassare Cozza, Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio

- Odo Colonna, Cardinal Deacon of S. Georgii ad velum aureum

- Petrus Stefaneschi, Cardinal Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria

Not participating, on the other hand, were Benedict XIII's loyal cardinals: Jean Flandrin, Pierre Ravat, Jean Martinez, Alfonso Carillo and Carlos Urriés (F. Ehrle, Archiv für Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 5 (1889), p. 402 n.; 7 (1900), 669). Ehrle also publishes ( Archiv für Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 7 (1900), p. 669; cf. Mansi Sacrorum Conciliorum 26, 1099-1104) a list of the prelates present at a Session of the Council of Perpignan (March 26, 1409) under the presidency of Benedict XIII, including the Cardinals:

- Iohannes [Flandrin] Sabinensis episcopus cardinalis.

- Petrus [Ravat] tituli sancti Stephani in Celiomonte presbiter cardinalis.

- Iohannes [Martinez de Murillo] tituli sancti Laurencii in Damaso presbiter cardinalis.

- Ludovicus [Fieschi] sancti Adriani diaconus cardinalis. [After Benedict's deposition by the Council of Pisa on June 5, 1409, he accepted Alexander V]

- Anthonius [de Challant] sancte Marie in Via lata diaconus cardinalis. [Joined the Council of Pisa on June 10, 1409]

- Karolus [Urriés] sancti Georgii ad Velum aureum diaconus cardinalis.

- Alfonsus [Carillo de Albornoz] sancti Eustachii diaconus cardinalis.

The Religieux de Saint-Denys claims that there were twenty-two participants in the Conclave in Bologna in 1410 (though he omits mention of Cardinal Antonio Gaetani, Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina). Only Salvador Miranda states that the number of cardinals was twenty-two: "The number of cardinal-electors was twenty two, but five of them were absent from the conclave." He apparently attributes this discrepancy from the vast majority of the sources to the death of Petrus Blavi, who died on December 12, 1409. But Petrus Blavi's name does not appear among the seventeen cardinals or six absentees in any of the sources (they are not confused by his name). Miranda includes Ludovico Fieschi as being present, in the face of the sources, which mark him absent. But Miranda forgets about Giovanni Migliorati, Cardinal Priest of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, one of Innocent VII's cardinals (Roman Obedience), who had been deprived of his Cardinalate by Gregory XII for attending the Council of Pisa. Migliorati took part in the Conclave at Bologna.

- Niccolò Brancaccio [Messana, Sicily], Bishop of Albano. Neapolitan Patrician, second son of Marino Brancaccio and Giacoma d'Aversa [He is C2 in the genealogy]. His election as Bishop was certified by the Council of Pisa, since he had left the Obedience of Benedict XIII. (died June 29, 1412 in Florence) [Baluze I, columns 1256-1260]

- Joannes de Bronhiaco (Jean Allarmet de Brogny) [Annecy in Savoy], Suburbicarian Bishop of Ostia and Velletri. retained as Vice-Chancellor by Alexander V [Martène-Durand VII, 1115] (a cardinal of Clement VII). [Blauzius I, 1353; Cardella II, 355-359]. called "Vivariensis" (died February 16, 1426)

- Pierre Girard de Podio [du Puy en Velay], Bishop of Tusculum. Created cardinal by Clement VII in 1390. retained as Major Penitentiary by Alexander V [Martène-Durand VII, 1115] (died November 9, 1415 in Avignon) called "Aniciensis"

- Enrico Minutoli [Neapolitanus], Bishop of Sabina (moved from Tusculum by Alexander V); He was Gregory XII's Bishop of Tusculum, but joined the Council of Pisa on September 14, 1408. Bishop of Bitonto (1382-1383); Archbishop of Trani (1383-1389); nominated Archbishop of Naples by Urban VI (1389) but never took possession, resigning in 1400. Appointed Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia on December 18, 1389, by Boniface IX of the Roman Obedience. Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore), 1396?-1412; his predecessor, Stephanus Palotius died on April 24, 1396. Canon and Prebend of Riccall in the Church of York, made possible by the promotion of Henry Beaufort to be Bishop of Lincoln on June 1, 1398 [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers V (1904), 290 (May 12, 1400); Le Neve, Fasti III, 209]. He was Chamberlain of the College of Cardinals in 1401 [Baumgarten, Untersuchungen und Urkunden über die Camera Collegii Cardinalium, p. 233 no. 326] He was Gregory XII's Bishop of Tusculum (from 1405), Cardinal Camerlengo of the Apostolic Camera, of the Roman obedience [from at least 1401; Guasti, e.g. 35-37]; but he joined the Council of Pisa on September 14, 1408. In 1409 he became BIshop of Sabina [Cardella II, 312-313]. He died in Bologna, where he was Legate in succession to Baldasarre Cossa (John XXIII), on June 17, 1412. [Cardella II, 312-313]

- Angelo d'Anna de Sommariva, O.Camald. [Laudensis (Lodi), Neapolitan], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Pudenziana. (a cardinal of Urban VI) [joined the Council of Pisa on September 14, 1408]. [Eubel I, 25] (died July 21, 1428). called "Laudensis"

- Petrus Fernandi de Frigidis (Pedro Fernández de Frías) [of Medina, Castilian], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Prassede.(a cardinal of Clement VII) Legate of Campania, Maritima et Sabina of Alexander V. Vicar-General of Rome [Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 315; Theoderic of Nyem, de schismate III. 53, p. 327 n. 4 Erler] "Oxomensis" (died September 19, 1420) [Cardella II, 359-360; Eubel I, 29]

- Corrado Caraccioli [Neapolitanus], son of Roberto, Patrician of Naples [The Cardinal is N2]. Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Crisogono. Nephew of Pope Boniface IX.. Legate in Lombardy (died February 15, 1411) S.R.E. Camerarius. called "Militensis"

- Francesco Uguccione [Urbino], Cardinal Priest in the title of Ss. IV Coronati. called "Burdigalensis". Doctor utriusque iuris. Sent to England in 1408 by the Cardinals of Pisa; as Archbishop of Bordeaux he was a vassal of King Henry IV [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1408, nos. lxvi, p. 227; Rymer VIII, p. 568]. Canon and Prebend of Andesakyre in the Church of Lichfield [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers VI, 197 (November 10, 1410)]. Canon and Prebend of York [Twemlow VI, 365 (July 14, 1412). He died on July 14, 1412.

- Giordano Orsini [Nobilis Romanus], son of Giovanni Orsini, Signore di Nerola, Marcellino, Vicovaro, Cantalupo, Bardella, Pacentro, Montemaggiore, Montelibretti e Scandriglia, Senatore di Roma 1350-1352; and Bartolomea Spinelli, daughter of Nicola Conte di Gioia and Grand Chancellor of the Kingdom of Sicily. Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Lorenzo in Damaso. (a cardinal of Innocent VII). Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica (died May 29, 1438) [Eubel I, 26; Cardella II, 321-324].

- Antonio Calvi [Romanus], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Marco (formerly S. Prassede, created by Innocent VII in 1405), Archpriest of the Vatican Basilica [L. Martorelli, Storia del clero vaticano, pp. 209-211]. He was the last of the cardinals to leave Gregory XII; he came to Pisa on June 16, 1409, and voted in the election of Alexander V. (died October 2, 1411) Called "Tudertinus" [Cardella II, pp. 329-330]. He was Rector of Shetlington in the diocese of Lincoln, and Archdeacon of Exeter, though there were other incumbents [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers VI (1904), 168 (July 14, 1410); Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae I, 394]. Appointed Canon and Prebendary of Cherminster and Byre in the church of Salisbury; Vicar of Okcham in the diocese of Lincoln [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers VI, 196 (October 16, 1410)]. He died on October 2, 1411.

- Giovanni Migliorati [Sulmonensis, Neapolitan], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Croce in Gerusalemme. Nephew of Pope Innocent VII [Theoderic of Nyem de schis. III. 38, p. 297 Erler]. Archbishop of Ravenna (1400-1405) [Martène-Durand VII, 1179], and thereafter Administrator of Ravenna until discharged on July 20, 1409 [Eubel, Romische Quartalschrift 10 (1896), 113-114]. He died on October 16, 1410. Doctor utriusque iuris.

- Landolfo Maramaldo, Neapolitan, Cardinal Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano [died 1415]. Protector of the Carmelites. Archbishop of Bari (1378-1384), but he was unable to take possession, since Queen Johanna of Naples adhered to the papacy of Pope Clement VII. He was appointed by "Urban VI" to compose the differences between the Malatesta and the Dukes of Urbino, at which he was successful. He was then sent to the Kingdom of Naples in aid of King Ladislaus. He was, however, deposed along with Pileus de Prato (who went over to Pope Clement VII in 1387) by "Urban VI", allegedly as supporters of Charles III of Naples; he was therefore ineligible to participate in the Conclave of the Roman obedience of 1389. He was rehabilitated in the Roman obedience by Boniface IX on December 18, 1389. Archdeacon of Dublin (from 1392), he resigned the office to Boniface IX in 1395 [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar IV, 504 (September 6, 1395); V, 595 (May 4, 1403); Henry Cotton, Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae II (Dublin 1848), 92-93; 128] He died at the Ecumenical Council of Constance in 1415. Former Vicar of Gregory XII for Perugia and adjacent areas [Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1408, no. lxiv, p. 226] Sent on April 4 to Germany to the Diet at Frankfurt by the Cardinals of Pisa [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1408, nos. lxvi, p. 227; Theoderic of Nyem de schismate III. 39, p. 298 Erler; Mansi Sacrorum Conciliorum 27, 339]. Sent to Germany to the Diet at Frankfurt by the Cardinals of Pisa [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1408, nos. lxvi, p. 227; Theoderic of Nyem de schismate III. 39, p. 298 Erler]. Sent to Spain after the election of 1409 to attempt again to get Benedict XIII to resign [Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 315]. Died at Constanz on October 16, 1415.

- Rinaldo Brancaccio [Neapolitan], Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Vito e Modesto [See Paolo Mazio, pp. 4, 10-14]. Elevated by Urban VI, a fellow Neapolitan, on December 17, 1384 at Nocera. He was Archpriest of the Liberian Basilica (S. Maria Maggiore) in succession to Cardinal Enrico Minutoli, who died June 17, 1412. Cardinal Brancaccio died on June 5, 1427.

- Baldassare Cossa (Coscia, Coxa) [of Procida, Neapolitanus] (aged ca. 40/42), Cardinal Deacon of S. Eustachio from February 27, 1402. (died December 22, 1419). Decretorum doctor. [E. Kitts, pp. 141-144, follows the authorites on the Cossa family back to their flimsy or unsupported origins. Only Theoderic de Nyem refers to Baldassare as a pirate, and even he adds ut fertur (de vita ac fatis Constantiensibus Johannis papae XXIII I. 1, p. 338 Hardt)]. Archdeacon of Bologna. 1392-1396. Chamberlain to Boniface IX, 1396, Protonotary Apostolic, and Auditor of the Rota. Named Legate in the Romandiola in 1403. On March 8, he was in Rome as Legatus of Pope Alexander [L. Martorelli, Storia del clero vaticano, pp. 216-217].

- Oddone Colonna [Romanus] (aged 45), fourth son of Agapito Colonna, Signore di Gennazzano, Capranica, Palestrina, San Vito et Ceciliano; of the Gennazzano branch of the family [He is K4]; his mother was Caterina, daughter of Giovanni Conti, a Roman Noble and Signore di Valmontone. Cardinal Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro. Legate to the Kingdom of Naples and King Ladislaus.

- Pietro Stefaneschi, alias de Anibalis [Romanus Transtiberanus], Cardinal Deacon of Ss. Cosma e Damiano (formerly Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria, 1405-1409, and again from 1410. This was to accomodate Cardinal Petrus Blavi (created by Benedict XIII in 1395), who was called the "Cardinal S. Angeli", but who died on December 12, 1409). [on 'de Anibalis' see Ehrle, Archiv fur Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 7 (1900), 643; Gregorovius VI. 2, p. 575]. Stefaneschi was made Papal Vicar of Rome when Gregory XII fled from his own condottiere Pietro Orsini on August 9, 1407. On April 11, 1408, he restored the offices of the Bandarenses in Rome, who remained in office until April 21, when Rome surrendered to King Ladislaus. Petrus Stefaneschi died on October 30, 1417.

- Antonio de Celancho [Antoine de Challant], Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata. Former Chancellor of the Count of Savoy. Abandoned Benedict XIII and joined the Council of Pisa at its Sixteenth Session on June 10, 1409. He was sent by pope John XXIII to England and Scotland as Legate [Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers VI, 175-181 (May 15, 1413)]. (died September 4, 1418)

- Guido de Malosicco (Guy de Malsec, Malesset), Limousin, of the diocese of Tulle, Suburbicarian Bishop of Palestrina (1383-1412), formerly Cardinal Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme (1375-1383). "Erat primus in ordine Penestrinus." [Souchon II, p. 44, n. 3; 45; and p. 51]. [He was close to 70 years of age, having participated in the disastrous conclave of 1378: Souchon II, p. 66 and n. 3].

Doctor in utroque iure. Papal Chaplain. Archdeacon of Corbaria in the Church of Narbonne. Bishop of Lodève (1370-1371). Bishop of Poitiers (1371-1376), Archdeacon of Condroz in the Church of Liège (from 1377) [Ursmer Berlière, OSB, Bulletin de la Commission Royale d' histoire 75 (Bruxelles 1906), 168-171]. Sent as Legate to England on December 30, 1378; returned to the Curia September 30, 1381 [Eubel I, p. 22 n. 5]. Attested as Canon and Prebend of Stillington in the Church of York on May 24, 1376 [Le Neve, Fasti III, 213]; "deprived" by "Urban VI", probably in 1378 [Bliss-Twemlow, Calendar of Papal Registers V, 208 (October 6,1399)]. Relative of both Pope Clement VI and Pope Gregory XI [Baluzius, 1144] (died April 4, 1412). "Pictavensis" "Penestrinus" [created by Gregory XI]. Author of a treatise on the need for a General Council, and of a speech to King Charles VI (1400) on the same subject [Martene-Durand, Thesaurus novus anecdotorum II (1717) 1193-1200; 1226-1230]. - Pierre de Thureyo [Thury], Cardinal Priest in the title of S. Susanna. Legate in France. On April 6, 1410, he presided at an investigation into the remains of S. Irenaeus of Lyon as Legatus a Latere [Acta Sanctorum Iunii V, p. 342]. (died December, 1410). His brother Philippe was Archbishop of Lyon (1389-1415), appointed by Pope Clement VII.

- Amedeo di Saluzzo, Cardinal Deacon of S. Maria Nuova. Cardinal Protodeacon [Ciaconius-Olduin II, 774]. Legate in Genoa (died June 28, 1419) [Baluzius I, column 1317] [He was not present at the Coronation: Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1410, no. 19, p. 320]

- Ludovico Fieschi [Genuensis], Cardinal Deacon of S. Adriano.(a cardinal of Urban VI). Nephew of Cardinal Giovanni Fieschi. He had left the Obedience of Benedict XIII after he had been condemned by the Council of Pisa, and had joined the Obedience of Alexander V. On May 23, 1410 he entered Bologna, too late for the Conclave [Eubel I, p. 25 and n. 3] (died April 3, 1423).

- Antonio Gaetani [Romanus], third son of Giacomo dell' Aquila Caetani, Signore di Anagni, Count of Fondi; and Sveva Sanseverino Signora di Piedimonte, daughter of Roberto Conte di Marsico. He was therefore nephew of Onorato Caetani, Count of Fondi, the enemy of Urban VI. Bishop of Porto e Santa Rufina (moved by Alexander V from Palestrina). Patriarch of Aquileia. Abbot Commendatory of SS. Bonifacio ed Alessio. Appointed Archpriest of the Lateran Basilica by Innocent VII. Appointed Major Penitentiary by Alexander V. He was too ill in his apartments at San Proculo to enter the Conclave (died January 11, 1412, according to his sepulchral inscription)

- Louis de Bar [son of Robert Duc de Bar], created Cardinal Deacon of S. Agatha by Benedict XIII in 1397. Cardinal Priest in the title of SS. XII Apostoli; he was ordained priest in late June, 1409, by Cardinal Guy de Malsec and Cardinal Niccolò Brancaccio, and promoted to SS. XII Apostoli by Pope Alexander, who had been the previous incumbent [Martène-Durand VII, 1120]. Cousin of King Charles of France. Legate in France in 1409 [Religieux de Saint-Denys XXX. 11). Legate in Germany. [Eubel I, 30 n. 3] (died June 23, 1430). His assistants at the Council of Pisa were Pierre d'Ailly and Jean Charlier de Gerson.

- Johannes Dominici, Cardinal Priest of S. Sisto (created on May 9, 1406, by Gregory XII of the Roman Obedience), sent to Hungary and Poland as Legate of Gregory XII, commissioned on January 8, 1409 [Twemlow VI, p. 99; Eubel I, 31 n. 5]. He died on June 6 or 10, 1419 at Buda.

During the Novendiales

As soon as he heard that Pope Alexander was dead, Louis II d' Anjou (1377-1417), who was a contender for the Kingdom of Sicily, and who was with his fleet between Marseille and Genoa, immediately sent an ambassador to Bologna to talk to the Cardinals before the Conclave began. According to Theoderic de Nyem [Dietrich von Nieheim] (Historia de vita Johannis XXIII pontificis Romani 18), he was especially interested in contacting the French cardinals. His message was to elect Baldassare Cossa as Pope:

Et quia Dominus Ludovicus Rex Siciliae nominatus, magnam paravit classem per mare, causa regnum Siciliae ante dictum, quod tunc praefatus rex Ladislaus tenuit, acquirendi, quam per mare de Marsilia per ripariam Januensem tunc temporis destinabat. Qui percipiens quod dictus Alexander Papa obierat, et succesoris electio instanter imminebat, quendam ambaxiatorem ad Bononiam destinavit recommendando dictum Balthasarum praefatis Dominis Cardinalibus, et praesertim de Gallia oriundis, et rogando, quod illum Papam eligerent, quia sperabat, se in acquisitione dicti regni cum adminiculo ipsius Balthasaris si, efficeretur Papa, indubie prosperari.

Cossa and Louis had campaigned together in the previous year in the successful effort to expel King Ladislaus from Rome.

Carlo Malatesta, Lord of Pesaro and Rector of the Romandiola for Pope Gregory XII, ws also prepared for Pope Alexander's death. He had been working constantly for two years on behalf of Pope Gregory and his religion. He had also come to realize that, as the host of Pope Gregory and his authorized agent, he had every right to do everything he could to recover the lands in central Italy and the Po valley which had been lost by the Church thanks to the schism. These included the rich cities of Imola and Mantua. He had intended to acquire as much of this territory as he could for himself, of course, but the presence of Pope Gregory, aged, impoverished, senile and ill-advised as he was, gave him the protective cloak he needed to advance his ambitions with propriety and a semblance of legality. Naturally, in carrying out his empire-building activities, he fell afoul of King Ladislaus of Naples (who had similar designs of recovering his ancestors' holdings in central Italy); of the condottiere Paolo Orsini (whose ambitions were to control Rome and the Campgna); of the French Louis II d'Anjou (who hoped to reacquire his inheritance which had been taken by King Ladislaus) and Marshal Boucicault, governor of Genoa; and of the King of the Romans.

Luckily for Malatesta, Pope Alexander and the Council of Pisa had managed to gratuitously insult Rupert, the King of the Romans, by transferring the title to Wenceslaus, king of Bohemia [Theoderic of Nyem, de schismate III. 53, p. 321 Erler]:

Aliud etiam maximum disturibum et inconveniens in tota Christianitate illico introduxit idem papa Alexander, quia in multis literis suis praefatum dominum Wenceslaum regem Bohemiae statim incepit nominare Regem Romanorum, supradicto domino Ruptero rege, qui in possessione tunc fuit regni Romani, ad hoc non vocato vel citato et nullo contra eum premisso processu. Et idem dominus Rupertus multum aegre ferens dicti domini Alexandri obedienciam propterea in ipsa Germania per plurimum turbavit conquerendo vehementer de ipso domino papa omnibus principibus et aliis potentibus de iniuria et violentia sibi facta, ut eius verba sonabant.

Luckily for the adherents of the Council of Pisa and for Cardinal Baldassare Cossa, King Rupert died shortly after Pope Alexander [Baronius-Theiner 27, sub anno 1410, no. 1, p. 300].

Unluckily for Malatesta, Bologna and northern Tuscany had been placed by Pope Benedict XI in the hands of Baldassare Cossa, who was now a Cardinal, and he had managed to build himself a more-or-less independent principality centered on his Legateship of Bologna, as Pope Gregory stumbled from one maladroit action to another under the influence of his nephews. Cossa had broken with Gregory, of course, by signing the call of the Cardinals for a General Council on August 30, 1408 [Martenè et Durand VII, 803-808], and Gregory had, of course, excommunicated him along with the others. His opposition to Gregory had profound practical effects on Gregory's grip on central Italy. Gregory's opinion of him had been published to the world [Baronius-Theiner sub anno 1408, nos. lxvi, p. 227]:

Hos tamen tempore et malitia longe ante praecessit iniquitatis alumnus, et perditionis filius damnatus Baldassar Cossa olim S. Eustachii diaconus cardinalis, qui tyrannice sub mentito nomine legationis nostras et sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae terras occupans, odiis et errorum furiis debacchatus fere per annum ante recessum olim cardinalium praedictorum de Luca studuit per nonnullos ad hoc invitatos, et falsitatibus informatos, nos perjurii et schismatis maculis infamare, et fecit quantum potuit ad hoc contra nos publice divulgari, successive sollicitans adversus nos insurgere cardinales, praelatos, principes, communitates et alias privatas personas, inter quos praecipue mendaciis, precibus, pretio ac pollicitationibus seduxit Petrum de Candia tunc Basilicae XII Apostolorum, et Joannem, timorem eidem incutiendo, tunc S. Crucis in Jerusalem presbyteros cardinales, ut sibi caeterisque rebellibus et schismaticis adhaererent. Nec his malis contentus excsecrabilia quaedam mandata poenalia fecit, ne quis nos papam diceret aut scriberet, arma nostra in nostrum et Sedis Apostolicae opprobrium turpiter et manifeste de locis publicis et privatis faciens deleri et captivari jubens: nuntios nostros et quamplures ad curiam adventantes perturbavit, et pecuniis et bonis aliis spoliavit, praecludens omnem viam, quam potuit, ne litterae nostrae per nos de indicto Concilio generali, et aliis veritatibus edocendis ad praelatos, principes et communitates, eorumque ad nos pervenirent.

Through his agents in Bologna, Malatesta was in contact with Cardinal Baldassare Cossa. As in the previous year, he had ambassadors at the Papal court, one ecclesiastical person and one layman—a Bishop and a lawyer. Each would have his own entrée and his own manner of presentation and argumentation. In 1409 the ambassadors had been Paul, Bishop of Cervi, and Johannes de Petra-Longa. In 1410, Paul of Cervi continued to serve, but the lawyer was Marcus de Veruculo.

Paul, as he himself explains in a letter to Carlo, he had left Bologna on Sunday morning, May 4, and was on the road toward when he heard of the death of Pope Alexander. He rushed to get back to Bologna, where he arrived near sunset, and had a meeting with Cardinal Cossa. He spoke with the Cardinal in terms of instructions which he had already received from Carlo. Evidently the two were in frequent communication during the Pope's final illness, and had various contingency plans ready. Paul began by suggesting that the cardinals were not happy with each other, and that, if led by their livor, they might well elect the wrong person to be pope. Such a person might well be hostile to Cardinal Cossa, which might lead to dissension and impede rather than advance the cause of unity in the Church. It might be better not to proceed to a new election. Cossa replied that he would gladly do it, if he could see a possible means (respondit quod libenter hoc faceret, si modum videret possibilem). Paul noted that Malatesta's suggestions would be a good plan. Cossa, however, remarked that the Way of the Council would take too long, and that even the Way of Renunciation (which he thought a good plan) was impeded by the impossibility of finding a common meeting ground. Cossa pointed out that Gregory was in the hands of King Ladislaus, who would never let him go. The Cardinals wanted no other course than to go forward with the election, because, in their view, without a Pope they had no incomes. Members of the Curia were going to go off because of the same shortage of funds. He also pointed out that they would lose Rome, which they currently held, if there were no Pope; likewise, that it would be a disaster for King Louis d' Anjou, who was shortly to arrive with a large army. His activities were supposed to be accomplished in the name of the Papacy (and it would look strange if there were no Pope for him to follow). The Bishop and the Cardinal parted, each sticking to his own positions. None of the Cardinals, the Bishop concludes, has given an indication of whom he would vote for. But Cossa, he thought, was genuinely afraid that a rival would be elected. Cossa was also worried about what the Bolognese would do; he had given them to understand that the Curia would reside in Bologna. The Cardinals were worried as well, and had approached the Lord of Imola with a view toward holding the Conclave there. Cossa thought they had done so in fear of intimidation (impressio) in Bologna.

It is apparent that Cossa is being quite straightforward with Bishop Paul, except perhaps in the matter of the opinions of the other cardinals as to where their votes might go. He surely had some ideas, and was equally surely working to mold their opinions. But Malatesta was a supporter of Gregory XII, by whom Cossa had been excommunicated and deprived. Nonetheless, he seems to have considered Pope Gregory to be the true pope (inquit ipse suo utens vocabulo, quod errorius quem Gregorium M. V. in verum et summum pontificem tenet)—or so he said. Cossa was certainly not prepared to be entirely frank with Bishop Paul or Carlo Malatesta.

Carlo Malatesta's reply survives. He comments, point by point, on Bishop Paul's report, mostly congratulating himself on his own sagacity and moral rectitude. He wants it understood that he is sincerely in favor of solving the problem of three popes and ending the Schism. He is opposed to the Conciliar solution, but believes that a formula can be found, to which Pope Gregory will agree. And in fact both Bishop Paul and the lawyer Marcus de Veruculo have a copy of his latest plan, which the Cardinals are to be made thoroughly aware of. As to the Cardinals and their financial problems, he quotes the Gospels, "Consider the lilies of the field." They should not, he says piously, consider their private ambitions ahead of the welfare of Christianity (privatas ambitiones publicae Christianorum rei praeponere).

At the same time, Marcus de Veruculo, Doctor of Laws, was in Bologna as Orator of the Lord of Rimini and Rector of the Romandiola. He began working the Cardinals furiously as soon as Alexander V was dead. On Wednesday, May 7, he received a packet of memoranda, sent by Carlo Malatesta, to be given to the Cardinals. There was also a letter for the cardinals from the Rector, begging them to read his memoranda, as they had not been able to do in 1409. On that occasion they had already gone into conclave; and they could not be reached by his ambassadors at the time, Paul, Bishop of Cervi, and Johannes de Petra-Longa, Doctor of Laws. These memoranda must have taken some time to prepare, an indication of Carlo's ongoing and active diplomacy. Malatesta was operating on behalf of Gregory XII, who was his "guest" in Rimini—or rather under the protection of King Ladislaus of Sicily. On Thursday, May 8, Veruculo presented himself at the Apostolic Palace, but found that the majority of the Cardinals had already gone to San Francesco, where the late pope had been buried and where the Novendiales were being observed. He followed, expecting to meet them in the Sacristy after Mass, where they gave audience, as was their custom. But few of them appeared. Nor did they appear for a meeting later in the day, due to a festival of S. Michael de Bosco to which many of the cardinals had gone after lunch.

On Friday, May 9, after the Requiem Mass, which he attended, Marcus de Veruculo met with eleven of the cardinals in the Sacristy of San Francesco. He presented his credentials, and a letter from Carlo Malatesta. He put forward Malatesta's proposals, point by point, and he also handed over the written copy which had been sent him for exactly that purpose. The Cardinals wanted him to leave the Sacristy and wait apart from the others. This gave the Cardinals the opportunity to examine the credentials and letter and discuss it among themselves. Verculo was recalled, and one of the older cardinals gave a response that they acknowledged that Malatesta was taking action only out of good motives. But the memorandum was long, and the Cardinals did not want to reply to it in such a short time, but only when they were all together and had had time to confer with one another. Marcus de Veruculo urged the Cardinals, that, since time was of the essence, they should determine a time to give him a reply to the memorandum. The Cardinals were noncommittal. The ambassador reported, too, in the Curia the general belief was that the Cardinals were proceeding to an election, out of motives of ambition (hic in curia apud majorem partem cardinalium, quod propter ambitionem cardinalium procedent ad electionem eorum novi pastoris). Each was thinking that he was the one who ought to be elected, and their politicking (prattica) was very active. He had also heard this directly from Cardinal Cossa. Cossa had also remarked that those who realized that their chances were hopeless would be open to bribery (faenerabilis foret); this included all of the Ultramontanes and Cardinal Gaetani. Cossa charged Veruculo to write to Malatesta about Cardinal Angelo d' Anna de Sommariva.

The Conclave, he notes, was being prepared and would take place in the Pontifical Palace, in the great upper room, where the Council of the People used to meet, and which was currently Cardinal Cossa's chapel. The Cardinal had told Veruculo that, for the present he did not want to answer Malatesta's inquiries, and certainly not on the record—which Veruculo thought was a bad sign rather than a good one.

On Monday, May 12, Cardinal Fernandez arrived in Bologna from Rome, where he had been serving as Alexander V's Vicar General [Theoderic of Nyem, de schismate III. 53, p. 327 n. 4 Erler].

On Tuesday, May 13, on the eve of the opening of the Conclave, the ambassador finally had his interview with the Cardinals. The meeting took place again in the Sacristy of S. Francesco, around the hour of terce, that is to say after the Requiem Mass and Absolutions of the Novendiales, in mid-morning. There were twelve cardinals present. The Vice-Chancellor, Cardinal Joannes de Bronhiaco (Jean Allarmet de Brogny), presided. Veruculo took the opportunity to produce the memorandum of Carlo Malatesta, and the entire document was recited into the record, with witnesses and a notary standing by to certify the event. In fact, the real purpose of the entire diplomatic mission was to put on record that Carlo and Gregory had tried one more time to offer a solution to the problem of the schism, even as the Cardinals were setting about the business of electing a new pope. There was nothing new, however, in Carlo Malatesta's proposals—and no reason to think that a serious offer was being made. It had given Malatesta an opportunity, though, to send agents into Bologna, and to intrigue with Cardinal Cossa over the papal election.

Bartolommeo Platina (de vitis pontificum, p. 283) has a brief notice of Cardinal Cossa's influence over the cardinals in Bologna. His generosity toward the cardinals, especially those of Gregory XII, who were poor, using the money he had acquired over nine years of rule in Bologna, brought him the papacy:

Verum post novem annos cum longa pace civitatem Bononiensem mirum in modum auxisset grandemque pecuniam sibi comparasset, mortuo Alexandro, largitione usus, maxime vero erga cardinales a Gregorio creatos, pauperes adhuc, pontifex creatur.

His observation is not unlikely, as Cossa's private remarks to Paul of Cervia indicate. A more generous (or neutral) assessment is given in a continuator of Ptolemy of Lucca (Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2, column 854, which is probably Platina's source), where, during the time of the Council of Pisa, Cossa spends the profits from his administration of Bologna on support for all the Cardinals of Gregory XII:

...sicque annis circiter novem prudentissime et fortissime illam [civitatem Bononiensem] gubernavit. Floruit multum civitas, et aucta est longa pace. Dum autem instaret tempus celebrandi Concilii Pisani, ipse omnes Cardinales, qui a Domino Gregorio recesserant, pecuniis legationis suae in Concilio sustentavit. Creatus Papa ad Electores Imperii misit excitando....

Theoderic of Nyem, however, has a somewhat different story to relate in his De vita et fatis Constantiensibus Johannis XXIII (1415). In this work, the sums are not great, and they are distributed to those few cardinals who were still with Pope Gregory in Lucca , rather than with the majority in Pisa:

Donando etiam, in odium dicti Domini Angeli, tunc Gregorii, certas pecuniarum summulas in subsidium expensarum aliquibus ex Cardinalibus ipsis, quos magis conspexerat talibus indigere. Per quos allecti fuere etiam reliqui antiqui domini Cardinales, qui usque tunc Lucae cum praefato Domino Angelo, tunc Gregorio remanserunt. Quod, ipso similiter dimisso, ad eandem civitatem Pisanam, ad eorum confines, unanimiter accesserunt.

Whether the offense is to be seen as smaller, because small sums of money were involved, and fewer Cardinals, or whether it is to be considered greater, because of the more obviously puropseful distribution of cash, is an interesting question. Details seem to be lacking, however, in all of the tales.

Conclave

The Conclave took place in the Apostolic Palace in Bologna (now called the Palazzo del Podestà), where the Pope had died: quarta decima praesentis mensis [May 14, 1410] in eodem palatio plena securitate ac votiva libertate firmato, conclave intravimus (Letter of the College of Cardinals to the University of Paris, May 17, 1410; Blumenthal, 490-492, is unaware of the letter); decima quarta die hujus mensis ante solis occasum, ingredientes conclave, domum videlicet quam dominus Alexander inhabitabat, dum ageret in humanis.(Religieux de Saint-Denys 31. 7). Ceremonies began on the evening of May 14, with the enclosing of the members of the Conclave, seventeen cardinals in all. The date of May 14 is also mentioned by John XXIII in his letter to the University of Paris on June 9, 1410 (Blumenthal is also unaware of this letter). A two-thirds majority would be twelve.

The Conclave took place in the Great Hall, called the Sala del Re Enzo, a very large room said to be 170 feet by 74 feet. Cardinal Cossa, who was Legate of Bologna, had been living in that palazzo and using the room as a chapel. The Cardinals began work on May 15, and reached agreement in a canonical election on the morning of May 17. The anonymous Vatican source that goes under the name Petrus Tillius reports [Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 311]: Sic igitur domini cardinales numero XVII fuerunt in dicto conclavi usque ad diem Sabbati inde sequentis videlicet XVII mensis Maii.

Immediately after hearing of the death of Pope Alexander, Louis d'Anjou, King of Sicily, sent an ambassador to Bologna to recommend to the Cardinals (especially the French ones) that they should elect Baldassare Cossa. His recommendation, it is alleged, was made entirely out of self-interest, expecting that Cossa would help him in the recovery of his patrimony in south Italy. This information comes from Theoderic de Nyem, the Papal Auditor and Scriptor, who was no friend of Cardinal Cossa [Historia de vita Johannis XXIII, cap.17]:

Qui percipiens quod dictus Alexander Papa obierat, et succesoris electio instanter imminebat, quendam ambaxiatorem ad Bononiam destinavit recommendando dictum Balthasarum praefatis Dominis Cardinalibus, et praesertim de Gallia oriundis, et rogando, quod illum Papam eligerent, quia sperabat, se in acquisitione dicti regni cum adminiculo ipsius Balthasaris si, efficeretur Papa, indubie prosperari.

It is said that, as well, after Pope Alexander had died, Baldassare Cossa asked several of the Cardinals to elect Cardinal Corrado Caraccioli, the Camerarius, as pope. He is said to have taken this step as a strategic move, knowing that, though Caraccioli was a good man, nevertheless he was uncultured and not disposed toward being Pope [Theoderic de Nyem, Historia de vita Johannis XXIII, cap.17]:

Unde rogabat plerosque ex eisdem Dominis Cardinalibus, quod Romae Dominum Conradum [Corrado Caraccioli, the Camerarius], titulo sancti Chrysogoni presbyterum, Cardinalem Melitensem vulgariter nominatum, natione Neapolitanum, in Papam eligerent. Qui licet esset in se bonus, erat tamen quasi omnino illiteratus, nec non valde grossus et indispositus ad Papatum.

But suggesting another candidate would make Cossa himself seem selfless and uninterested in seeking power either for himself or his friends. Though Theoderic is painting a dark picture of Cossa's activities, neither of these anecdotes is improbable or, in fact, discreditable. Such things went on at all conclaves.

Henri Sponde [Henricus Spondanus] preserves a more interesting anecdote, one which he says comes from an anonymous Bordelais [Auctor Burdegalensis]. While no such manuscript has yet been produced, it is perfectly likely that Sponde did see a manuscript in Bordeaux or thereabouts, written perhaps by a follower of Cardinal Francesco Uguccione, the Cardinal of Bordeaux, who was present at the Conclave. The Bordelais alleges that Cossa would have easily been elected by the Neapolitan and French Cardinals, had it not been for Cardinal Uguccione, who did not want to consent to the election:

Et Auctor Burdegalensis, de quo alias, fuisse quidem eum a Cardinalibus Neapolitanis et Gallicis facile electum; at vero cardinalem Burdegalensem numquam voluisse consentire; dicentem se potius eum in Regem, vel Imperatorem electurum: sed et cardinales Romanos, qui tres erant numero, restitisse ei initio, verum postea acquievisse; at Burdegalensem firmum in sua sententia permansisse.

Uguccione said he would rather see Cossa elected King or Emperor than Pope. Three Roman Cardinals (Calvi, Colonna, Orsini, Stefaneschi ?) stood against Cossa at the beginning, but later agreed to go along. But Uguccione stood firm in his statement against Cossa.

The Cardinals themselves admit that they had a struggle, but that finally they reached agreement (their letter is dated May 17, the day of the successful election):

quarta decima praesentis mensis in eodem palatio plena securitate ac votiva libertate firmato, conclave intravimus; et multiplicibus circa tam sublimem materiam habitis coloquiis atque tractatibus, ut Petri navicula, fluctuum agitata turbinibus, ad portum salutis sub remigio doctissimi piscatoris quo carebat reduci posset, vota nostra in reverendissimum in Christo patrem et dominum Baldassarem, tunc Sancti Eustachii diaconum cardinalem, utriusque juris doctorem, scientiae claritate conspicuum, ac spiritualium et temporalium donorum dotibus illustratum, opere ac sermone potentem, et qui, Deo auxiliante, indirecta dirigere et convertere aspera in vias planas sciet, poterit atque volet, ac fluctibus agitatam diutius naviculam ad portum reducere salutarem; sicut experimentis innumeris in gerendis rebus statum hujusmodi Ecclesiae concernentibus cunctis contemplari volentibus demonstravit gestaque sunt mundo notissima; ad culmen dignitatis apostolicae, Divina superillustrante Clementia, ac suis exigentibus meritis, nec immerito ascensurum unanimiter direximus ac concorditer; ita ut in pluralitate unitas nullaque contrarietas apparerent, ac eundem dominum Baldassarem in nostrum elegimus dominum atque patrem, Christique vicarium, ac beati Petri verum et unicum successorem, tandem eligentem se Iohannem XXIII. appellari:

The eventual unanimity was finally achieved on May 17, as John XXIII himself confirms in a letter of June 9, 1410, to the University of Paris:

quarta decima die instantis mensis, juxta morem a venerabilibus fratribus nostris ejusdem ecclesiae Cardinalibus, de quorum numero tunc eramus, discrepante nemine, decima septima ipsius mensis, licet insufficientibus meritis, fuerimus evocati....

The clearest clue may actually be a phrase in the Cardinals' letter on the day of the Election; ita ut in pluralitate unitas nullaque contrarietas apparerent. They wanted to reach unanimity, not just the required two-thirds under the Constitution of Alexander III. This was, after all, an election to settle the Schism, to bring unity out of discord, and any appearance of dissention among them in their election might provide one party or another in the Schism something to fasten on to as an argument for invalidity. The vote, therefore, had to be unanimous.

Enthronement and Ordination to the Priesthood

That same manuscript that goes under the name Petrus Tillius [Baronius-Theiner 27, p. 311] is the most specific text on the order of events after the conclave:

in dicto conclavi et de numero dictorum XVII existens in summum Pontificem concorditer extitit electus, sicut ipsi domini cardinales toti orbi nuntiare verbo et scriptis curaverunt, et in Ecclesia Bononiensi more solito statim per eos inthronizatus, qui Joannes XXIII voluit nominari. Et in crastinum coram eo dominis cardinalibus, qui in conclavi fuerunt, praesentibus, predictus dominus Ostiensis missam in Pontificalibus solemniter celebravit, ipso in capella magna dicti palatii Apostolici Bononiensis in cathedra, in statu et habitu papalibus existente. Deinde sequenti die Sabbati, quae fuit XXIV dicti mensis Maii, in presbyterum per dictum dominum Ostiensem ordinatus extitit, et die Dominica sequenti XXV ejusdem mensis fuit per eumdem dominum Ostiensem consecratus in Ecclesia S. Petronii Bononiensis

The source is taken (e.g. by Salvador Miranda) to state that Baldassare Cossa was "[o]rdained on Saturday May 24, 1410 in the Apostolic Palace in Bologna." This seems to be a hasty reading of the Latin text, which actually says that, on the day of the Conclave, the new Pope was enthroned in the Cathedral of Bologna in the usual way; and that on the day after the Conclave [apparently, May 18], in the presence of the new pope, and with the Lords Cardinals being present, the Bishop of Ostia celebrated a Pontifical Solemn Mass, in the same large chapel of the Apostolic Palace in Bologna, with the Pope on his throne and with papal vestments and apparatus. Then on the following Saturday, which was May 24, he was ordained to the priesthood by the same Bishop of Ostia, and on the following Sunday, the 25th (it being contrary to the canons to bestow more than one of the major orders on the same day), he was consecrated [bishop] by the same Bishop of Ostia in the [Cathedral] Church of S. Petronius in Bologna. Three venues are mentioned in three clauses: the Cathedral, the Chapel and again the Cathedral. Each is associated with an event: enthronement in the Cathedral; first papal mass in the Chapel; and sacred orders in the Cathedral. The text is most naturally to be taken to say that the new Pope was ordained to the Priesthood in the Cathedral, not in the chapel of the Apostolic Palace.

Coronation

Baldassare Cossa was ordained a priest on Saturday, May 24, 1410, by Cardinal Joannes de Bronhiaco (Jean Allarmet de Brogny), Bishop of Ostia, in the Basilica of S. Petronio. On Sunday, May 25, 1410, he was consecrated a bishop by the same prelate, and he said his first Mass. After the Mass, John XXIII (Baldassare Cossa) was crowned on a high wooden platform in the square in front of the Cathedral of S. Petronio [above], on Sunday, May 25, 1410, by Cardinal Rainaldo Brancaccio, in the absence of Amadeo de Saluzzo the Cardinal Protodeacon. (Blumenthal, 492; Baronius-Theiner, sub anno 1410, pp. 311-312) [Brancaccio was not Protodeacon, as Salvador Miranda alleges; Cardinal de Saluzzo was, and he held the senior deaconry, S. Maria Nova].

Deinde sequenti die Sabbati, quae fuit XXIV dicti mensis Maii, in presbyterum per dictum dominum Ostiensem ordinatus extitit, et die Dominica sequenti XXV ejusdem mensis fuit per eumdem dominum Ostiensem consecratus in Ecclesia S. Petronii Bononiensis, et demum, ante et extra dictam Ecclesiam in scadafalco ligneo alto et eminenti, missa prius post dictam consecrationem per eum dicta sive celebrata, per dictum dominum de Brancaciis primum diaconum cardinalem, absente praedicto domino de Saluciis, publice et solemniter coronatus extitit.

The image above shows the site of the coronation, the piazza between the Palace of the Podesta and the Cathedral (white roof at extreme bottom).

Bibliography

"Vita Alexandri Papae V," "Vita Joannis Papae XXI. vulgo XXIII," J. D. Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum 27 (1784) 503-505.

"De Johanne XXIII.," in Ludovico Antonio Muratori (editor), Rerum Italicarum Scriptores III. 2 (Milan 1724), columns 846-857.

B. Platina (edited by Onuphrio Panvinio), B. Platinae de vitis pontificum Romanorum (Coloniae: apud Maternum Cholinum 1568). "Innocentius VII" (pp. 278-280); "Gregorius XII" (pp. 280-282); "Alexander V" (pp. 282-283); "Iohannes XXIII" (pp. 283-287). Bartolommeo Platina e d'altri autori, Storia delle vite de' pontefice Tomo Terzo (Venezia: Domenico Ferrarin 1763), "Innocenzio VII" (pp. 284-287); "Gregorio XII" (pp. 288-295); Alessandro V (pp. 296-298); "Giovanni XXIII" (pp. 299-312).

George Williams (editor), Memorials of the Reign of King Henry VI: Official Correspondence of Thomas Bekynton, Secretary to King Henry VI, and Bishop of Bath and Wells Volume II (London 1872), no. CCXLIII, pp. 109-112. [letters to the University of Paris, by the Cardinals and by John XXIII]

Theodericus de Nyem [Dietrich Niem]: Georg Erler (editor), Theoderici de Nyem de scismate libri tres (Lipsiae 1890). Georg Erler, Dietrich von Nieheim [Thoedericus de Nyem]. Sein Leben und seine Schriften (Leipzig: Alfons Dürr 1887). [ca. 1338/1348—1418] [Theoderic is completely hostile to most of the popes he worked for and wrote about, especially Gregory XII, Alexander V and John XXIII]

Theodericus de Nyem, "Informacio facta cardinalibus in conclavi ante eleccionem pape Joannis XXIII. moderni," in Erler, Dietrich von Nieheim [Thoedericus de Nyem]. Sein Leben und seine Schriften (Leipzig: Alfons Dürr 1887), Beilage II, pp. XXX-XLI.

Theodericus de Nyem, "De vita ac factis Constantiensibus Joannis Papae XXIII. usque ad fugam et carcerem ejus," in Hermann von der Hardt, Res Concilii Oecumenici Constantiensis II, XV, pp. 334-460. [very hostile]

Antonius Petri, Diarium Romanum [1404-1417] [Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores XXIV, 973-1066; Savignoni, "Giornale d'Antonio di Pietro dello Schiavo," Archivio della R. societa Romana di storia patria 13 (1890), 295-359]

L. Bellaguet (editor and translator), Chronique du Religieux de Saint-Denys Tome quatrième (Paris: Crapelet 1842), Liber XXXI [Latin text and French translation].

Edmundus Martène et Ursinus Durand, Veterum Scriptorum et Monumentorum Amplissima Collectio Tomus VII (Parisiis: apud Montalant 1733) Stephanus Baluzius [Étienne Baluze], Vitae Paparum Avinionensium 2 volumes (Paris: apud Franciscum Muguet 1693)

Augustinus Theiner (Editor), Caesaris S. R. E. Cardinalis Baronii, Od. Raynaldi et Jac. Laderchii Annales Ecclesiastici Tomus Vigesimus Septimus 1397-1423 (Barri-Ducis: Ludovicus Guerin 1874) [Baronius-Theiner].

Jacques Lenfant, Histoire du Concile de Pise Tome premier (Amsterdam Pierre Humbert 1724), Livre IV (esp. pp. 324-328); Tome second (esp. pp. 2-12). Joannes Dominicus Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima Collectio Tomus vicesimus-septimus (Venetiis: Apud Antonium Zatta 1784). Carl Joseph von Hefele, Conciliengeschichte Sechster Band. Zweite Auflage (ed. Alois Knöpfler) (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder 1890), pp. 982-1041; Siebenter Band, pp. 5-8. Hefele, Histoire des Conciles (ed. H. Leclercq) VII (Paris: Letouzey 1916). Franz Ehrle, "Aus den Acten des Afterconcils von Perpignan 1408," Archiv fur Literatur- und Kirchengeschichte 7 (1900).

H. B. Sauerland, "Gregor XII. von seiner Wahl bis zum Vertrage von Marseille (30 Nov. 1406-21 April 1407)," Historische Zeitschrift 34 (1875), 74-120. J.-B. Christophe, Histoire de la papauté pendant le XIV. siècle Tome troisième (Paris 1853), Books 16 and 17. F. Gregorovius, History of Rome in the Middle Ages, Volume VI. 2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell, 1906) [Book XII, chapter 5] Eustace J. Kitts, In the Days of the Councils. A Sketch of the Life and Times of Baldassare Cossa (afterward Pope John XXIII) (London 1908). Noël Valois, La France et le Grand Schisme d'Occident Tome quatrième (Paris: Alphonse Picard 1902)

Martin Souchon, Die Papstwahlen in der Zeit des Grossen Schismas Zweiter Band (Braunschweig: Benno Goeritz 1899). Hermann Blumenthal, "Johann XXIII., seine Wahl und seine Persönlichkeit. Eine Quellenuntersuchung," Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 21 (Gotha 1901), 488-516, at 491-492. Paolo Mazio, Di Rinaldo Brancaccio Cardinale ... e di Onorato I. Caetani Conte di Fondi commentario storico (Roma: Salviucci 1845). L.-H. Labande, "Un légiste du XIVe siècle: Jean Allarmet, Cardinal de Brogny," Mélanges Julien Havet (Paris 1895) 487-497. Erich Koenig, Kardinal Giordano Orsini (†1438). Ein Lebensbild aus der Zeit der grossen Konzilien und des Humanismus (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder 1906).

Cesare Guasti, "Gli avanzi dell'Archivio di un pratese Vescovo di Volterra che fu al Concilio di Costanza," Archivio storico italiano Quarta serie 13 (1884), 20-41; 171-209; 313-372. [Stefano Geri Boni di Prato (Bishop of Volterra 1411-1435)].

Leonce Celier, "Sur quelques opuscules du camerlingue François de Conzié," Mélanges d' archéologie et d' histoire 26 (1906), 91-108.